Phan Duc Hieu and Nguyen Thi Luyen[1]

The past 30 years of renewal sees Vietnam liberalizes and expands its domestic market while step by step integrating into the world economy. As a result, different types of markets in the economy have increasingly developed and improved. In order to increase the level of market competition, many significant reforms have been carried out, such as removing and reducing numerous competition restrictions and anti-competition practices, narrowing down the scope of state monopoly and liberalizing the prices of most goods and services to more accurately reflect the supply-demand relation in the market. These reforms have helped drive up the development of businesses and boost competition among market players.

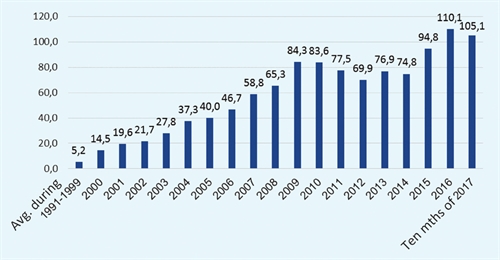

However, the Vietnamese economy still lacks dynamism. The economic growth tends to slow down while growth quality shows modest improvement. Productivity and productivity growth remain low and social resources are still used inefficiently. The average economy growth rate was 7.6 percent during the 1990-2000 period but fell to 6.8 percent in 2001-10, then 5.91 percent in 2011-15. The growth target of 6.5-7 percent set for the 2016-2020 period seems hard to achieve.

|

| Source: Ministry of Planning and Investment |

The main cause behind the above situation is the existence of many competition barriers. At the same time, unfair competition practices remain rampant. The right to freedom of enterprise has not yet been fully guaranteed. The investment and business environment is not yet truly open and transparent, failing to guarantee sound and fair competition. The level of government intervention in different economic sectors remains rather high while the control of monopoly is still ineffective. Vietnam still lacks a comprehensive and effective competitive policy to boost market development and increase productivity. Compared to international practices and experiences, Vietnam’s competition policy has revealed many weaknesses which need to be redressed in order to foster competition in the market.

The national competition policy framework

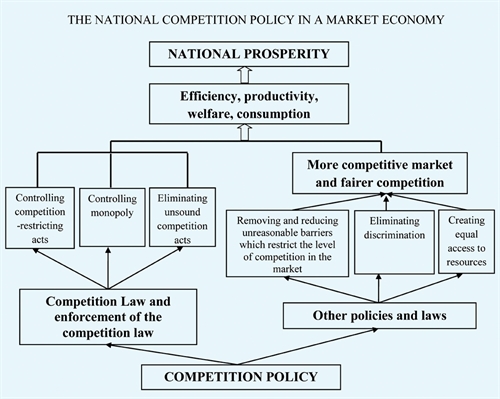

Competition policy is generally understood as all measures taken by the state to guarantee the existence of competition as a regulatory tool of the market economy. In other words, competition policy is a collection of policies and laws to control monopoly, fight against unsound competition and develop markets, including regulations on market entry and business as well as intervening actions to be taken by the government to help businesses compete on a level playing field.

The purpose of competition policy is to boost fair competition among economic entities for higher efficiency and productivity in different types of markets. This also means that the ultimate goal of competition policy is to increase productivity and economic efficiency.

In a market economy, the national competition policy consists of two major components.

The first component is the competition law and its enforcement. The competition law governs behaviors of businesses and businessmen to ensure sound competition in the market and to control, reduce and eliminate their competition-restricting agreements, abuse of monopolistic or market-dominating positions and unsound competition practices.

The second one is the system of laws and policies to improve (upgrade) the levels of market development and market competition, thus creating an equal business environment. Although the contents and significance of this component vary among different countries, good international practices reveal that it normally includes policies and laws to: (i) eliminate and reduce to the utmost business freedom and autonomy restrictions and market entry barriers; (ii) remove policies and laws that create discrimination among market players and concurrently establish institutions to ensure a fair and equal business environment; and (iii) build institutions to guarantee equal access to social resources as well as natural monopolies managed by the state.

Vietnam’s competition policy: present situations and problems

|

| Source: Ministry of Planning and Investment |

Over the past 30 years of economic renewal, numerous mechanisms and policies have been adopted and improved, making the Vietnamese economy more competitive and effective. From the perspective of the above-said national competition policy framework, Vietnam has attained certain achievements but also encountered a lot of problems.

The competition law and its enforcement

The current legal framework has identified and provided a rather complete list of anti-competitive practices of businesses but still contains loopholes.

The current Competition Law has specified many anti-competitive acts of businesses such as entering into competition-restricting agreements, abusing the monopolistic or market-dominating position, and economic concentration acts. However, the enforcement of these regulations remains unsatisfactory as shown in the too small number of anti-competition cases that have been settled[2]. This can be attributed to the fact that the current competition law fails to cover all anti-competitive practices in reality, especially “implicit” competition restriction arrangements. Besides, the Competition Law and specialized laws provide different penalties on anti-competitive acts, causing difficulties to their imposition. Shortage of qualified staffs and resources for law enforcement activities is another limitation.

Laws and policies for improving the level of competition and ensuring fair competition

Firstly, competition restriction regulations have been reviewed, removed or revised but there still exist many regulations hindering market entry and restricting competition and the right to freedom of enterprise of people and businesses.

In order to boost competition, Vietnam has reviewed, removed or revised numerous regulations, particularly business registration regulations, and slashed the number of conditional business lines. As a result, the number of businesses registered for establishment has significantly increased, especially in the 2015-17 period.

However, there still exist many barriers to market entry (business startup), including cumbersome formalities and procedures, making the country’s ranking rather low compared to other countries in the world.[3] Sectoral market access is far from simple due to strict production capacity conditions.[4] These barriers favor large-sized businesses but hinder the market entry of small- and medium-sized ones, thus impeding competition in the market and hampering innovation, productivity and competitiveness of businesses and the economy as a whole.

Moreover, the “disguised” business conditions such as administrative procedures, standards, technical regulations, and sectoral and product master plans[5] have become “sub-licenses” to obstruct investment activities of businesses, affecting market access and competition.

Secondly, mechanisms and policies that discriminate market players have been minimized to create an equal business environment. Many important solutions have been realized to ensure competitive neutrality of state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Nevertheless, fair and equal competition between SOEs and other businesses has not been truly guaranteed. SOEs have not yet ensured competitive neutrality while state institutions have not yet upheld neutral treatment toward SOEs and other businesses.

The number of sectors and fields with the State’s participation has markedly decreased. Some state-monopolized sectors have been restructured to offer more opportunities for other economic sectors. Accordingly, the number of wholly state-owned businesses has been cut down drastically. In addition, the divestment from non-core business sectors and from businesses in which the State does not need to hold shares, equitization and the opening of some monopolistic sectors have created opportunities for other economic sectors, contributing to increasing competition in the market in favor of consumers, especially in the telecommunications, aviation and television sectors.

Yet, there remain not a few inequalities between SOEs and privates businesses in the areas of tax, access to land, natural resources, loans and state investment, and efficiency evaluation. Particularly, SOEs are not yet required to operate in line with market rules and prices in development investment and business activities. Neither are they subject to market or competition discipline or pressure to generate profits under market rules.

|

| Mai Linh Group now provides motorbike taxi services to compete with UberMoto and GradBike __Photo: Internet |

Thirdly, institutions enabling market players to access social resources and state-managed natural monopolies have been put in place but still reveal limitations and contradict the market mechanism.

In several sectors, the right to access infrastructure facilities essential for competition (state-managed natural monopolies) has been guaranteed, such as the right to access airport infrastructure or telecommunications networks. Institutions that guarantee the right to access essential infrastructure facilities and regulations on connection charge rates have facilitated market entry for new businesses as well as responded to market development demands, making the market more competitive and services more diverse. However, access to essential infrastructure facilities in several industries remains problematic. Essential infrastructure systems are in the hands of state economic groups, state corporations or SOEs or under the management of ministries that concurrently manage related SOEs while there are insufficient mechanisms for access to these infrastructure facilities for all stakeholders. The separation of natural monopolistic stages for developing competitive markets in other stages is still carried out at a slow pace, thus restricting other entities from participating in the market and fail to put pressure on SOEs to renovate themselves and raise their competitiveness.

Despite the increasingly improved institutions guarantee the right to access social resources, such access is far from competitive and market-based because the market of production factors has not yet developed to meet the requirement of effective distribution of resources.

The above situation is owing to several causes. Awareness about competition and the role of competition in a market economy remains inadequate; state management methods are still heavily affected by the way of thinking under a centrally planned economy, failing to catch up with the development and integration trends; the role of the State, state economy and SOEs has not yet been clarified; the State-market relationship remains unclear and problematic; and there are no mechanisms for assessing competition impacts of policies and laws, especially a mechanism for quality assessment and management of business regulations.

Recommendations

First, it is necessary to raise awareness and renovate thinking about competition and the role of competition in a market economy. Competition must be regarded as a motive to promote creativity, innovation and development, raise productivity, quality and dynamism and bring about progress and benefits to the society. Fair and equal competition must be considered the key to a market economy. When issuing any regulation or policy or management or intervention measure, policymakers and lawmakers must answer the question whether it encourages or restricts competition. If restricting competition, it must not be issued; if it is to be applied in rare cases, it must be proved that benefits brought to the society surpass expenses incurred by the society.

Second, state management methods should be renovated toward facilitating business activities and equal competition. It is necessary to review and reduce institutional barriers to market entry, such as cutting unnecessary expenses for businesses to promote private investment in all sectors not banned by law. In the immediate future, efforts should be focused on reviewing master plans, business conditions and practice licenses. In the long term, all legal and administrative documents should be reviewed in order to get rid of competition-obstructing or -restricting regulations.

Third, the role of the State, state economy and SOEs in a market economy should be properly determined to reduce to the utmost the State’s participation in economic activities. State monopolies should be restructured to ensure equal competition and promote development of the private sector. The State’s role in the economy as a direct investor (in production and business activities) should be changed to that a regulator and fosterer.

The number and scope of sectors and fields of operation of SOEs should be further reduced. State monopolies should be narrowed down and abolished in inessential areas. Sectors and markets under natural and state monopolies should be restructured, especially infrastructure facilities and networks in the direction of separating stages of natural monopoly from other competitive stages to be placed under a separate management mechanism. Mechanisms guaranteeing equal access to essential infrastructure facilities and networks of natural monopoly should be studied and adopted to create competition and ensure effective use of resources. Conditions should be created for the development of the private economic sector through opening economic sectors for its participation, especially public services and energy, telecommunications and aviation sectors still dominated by SOEs.

A level playing field should be created for all businesses by further removing exclusive incentives for SOEs (subsidies, biased treatment in taxation or access to land and credit, and public procurement). Market, competition and financial discipline should be imposed on SOEs to ensure fair competition with other businesses. Unequal and unreasonable preferences should be removed while competitive neutrality should be realized between SOEs and other businesses, ensuring adherence to the principles of equal treatment among different economic sectors. Specific regulations prohibiting the grant of priorities to SOEs in all business aspects, from access to resources, market entry, capital, debt, business result to withdrawal from market, should be issued.

Fourth, the state-market relationship should be clarified. The State should operate according to the market and its intervention in the economy must not contravene market rules. The State’s intervention and regulation should be placed within the law-prescribed, must not go beyond the objective limits of the market and must be aimed at overcoming market failures. Mechanisms and policies should be improved to foster different types of market, especially the market of production factors.

Fifth, it is necessary to create and supervise mechanisms for assessing competition impacts of policies and laws, especially a mechanism for quality assessment and management of business regulations. The responsibility of ministries and sectors and the competence of the competition authority to assess competition impacts in the course of making and issuing new policies and regulations should be clarified. Also, responsibilities of state agencies and SOEs and measures to handle their violations of competition principles and regulations should be clearly identified so as to maintain a really competitive, productive and efficient economic climate.

The competition authority should be strengthened to ensure its independence and self-decision. The competence of other state institutions to give instructions to the competition authority should be clearly determined to avoid their intervention in the authority’s professional activities.

Besides, the market regulation apparatus should be reorganized in the direction of separating the market regulation body from the policymaking body and businesses to ensure its neutrality and effective operation. It is necessary to further restructure SOEs, abolish the “dual” role of ministries to both perform the state administration of businesses and act as the owner of state capital in businesses and regulate the market.-

______________

References:

Ministry of Industry and Trade (2017), Review report on 12 years’ implementation of the Competition Law, included in the dossier on the Competition Law.

Ministry of Planning and Investment (2016), Report on the implementation of Resolution 19/2016/NQ-CP of April 28, 2016, on major tasks and solutions for improving the business climate and raising national competitiveness for 2016-17, with orientations toward 2020 (for the Government’s September 2016 regular meeting).

Ministry of Planning and Investment (2017), Overall scheme on the national competition policy, draft version dated October 20, 2017.

Ministry of Planning and Investment (2017), Report No. 6770/BC-BKHDT dated August 18, 2017, on the results of reviewing the reports on business investment conditions, made by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) and Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM).

Ministry of Finance (2016), Situation of the restructuring of state-owned enterprises during 2011-15, with orientations and solutions for the 2016-20 period.

Government (2016), Review report on planning work, included in the dossier on the Planning Law.

Government (2016), Report No. 428/BC-CP dated October 17, 2016, on investment, management and use of state capital at enterprises nationwide in 2015, presented to the 2nd session of the 14th National Assembly.

Vietnam Competition Authority (2017), Model and legal status of the competition authority (presented at the Workshop on International Experience in Building the Competition Law, organized by the Vietnam Competition Authority on February 27, 2017).

Nguyen Dinh Cung (2017), Renovating the management of socio-economic development toward economic restructuring and growth model change (presented at the meeting with postgraduates held on February 18, 2017, at CIEM).

Dau Anh Tuan, Nguyen Thi Thu Trang, Nguyen Thi Dieu Hong and Pham Ngoc Thach (2016), Building a healthy and equal competitive environment, Chapter 3, in Dinh Tuan Minh and Pham The Anh (chief editors), From a managing state to a facilitating state, Tri Thuc Publishing House, Hanoi, 2016.

David Havyan (2017), Components of efficiency, Issue 62, March 2017, https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Network%20march%2017.pdf.

Frederick G Hilmer, Mark Rayner and Geoffrey Taperell (1993), National Competition Policy (the Hilmer Review), Commonwealth of Australia.

Ian Harper, Peter Anderson, Su McCluskey and Michael O’Bryan OC (2015), Competition Policy Review, Final Report, March 2015, Commonwealth of Australia 2015.

Nguyen Dinh Cung (2017), Competition and efficiency, Consultancy workshop on the national competition policy framework, held in Hanoi on May 25, 2017.

OECD (2011), Competition Assessment Toolkit. Volume I: Principles, Version 2.0.

Central Institute for Economic Management (2015), State-owned enterprises and market distortions, Finance Publishing House, Hanoi, 2015.-

Nguyen Thi Luyen, Director, Department for Economic Institutions, Central Institute for Economic Management.