Erwin Schweisshelm[1]

On August 4, 2015, after two and a half years of negotiations, Vietnam and the European Union agreed on the text of a free trade agreement. Two months later, the trade ministers of twelve Asian and Pacific states initialed the text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP).

The United States and the European Union hold the view that the Vietnam-EU and TPP agreements not only concern dismantling tariffs and investment disincentives, but also guaranteeing social and ecological standards.

Whilst the EU leans towards an approach that closely resembles encouragement, the US, the biggest country in the TPP, insists that Vietnam not only grant concessions on the wording of the agreement, but also harmonize its labor and trade union legislation with International Labor Organization standards and beyond with immediate effect.

Whether enforcement of standards will really take place or the labor chapter is just a placebo for the many critics of such free trade agreements remains to be seen. The experiences with the Central American Free Trade Agreement (2005) and the trade agreement between the EU and South Korea (2011) give more cause for skepticism.

The EU one step ahead of the US

After negotiations on a free trade agreement between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the European Union reached an impasse several years ago, on August 4, 2015, Vietnam became the second Southeast Asian country, after Singapore, to seal a trade agreement with the EU. Last year, Vietnam ranked twenty-ninth among the EU’s trading partners, while the union represented Vietnam’s second largest export market, after China. Within the EU, Germany is its biggest customer. Vietnam’s major export items are electronic products, textiles and clothing, shoes, coffee, and seafood, while the EU primarily exports machinery, vehicles, and pharmaceutical products to Vietnam. Some technical issues remain unaddressed in the agreement. For instance, it was agreed to set aside the matter of investor protection until the EU develops a mechanism based on international legal standards independent of the previous investor-state dispute settlement method. After all outstanding issues are resolved, “legal scrubbing” will proceed and the text translated into the 24 official EU languages. The ratification process will subsequently get under way. The agreement is expected to come into force in 2017 or early 2018.

This is the most ambitious free trade agreement the EU has thus far concluded with a developing country. Almost 99 percent of all tariffs between Vietnam and the union will be abolished: 65 percent for Vietnam and 85 percent for the EU when the agreement comes into force and the remainder after seven years (for Vietnam) and ten years (for the EU). The agreement will directly affect 70 percent of Vietnamese exports, especially in such labor-intensive sectors as textile and clothing, shoes, and electronics. Regarding apparel, the production steps of weaving and sewing need to be carried out in Vietnam to benefit from customs advantages. This is intended primarily to prevent China from obtaining duty-free access to the European market for its textile products by way of indirect access via Vietnam. This means that in the clothing sector, Vietnam must create an entire value-added chain.

|

| Producing garments at Ho Guom Garment Company’s Hung Yen-based Enterprise 3 for export to the US __Photo: Tran Viet/VNA |

TPP Home and Dry with the EU-Vietnam Agreement?

After five years of negotiations, the text of the TPP was approved on October 5, 2015, by twelve states on both sides of the Pacific, including the US and Vietnam but excluding China. The TPP is even more important for Vietnam in terms of volume than the agreement with the EU. There were serious disagreements until the end, for example, between Japan and the US regarding the automobile sector and between the US and Australia over patent protection, especially for expensive and essential medicines. Sizeable obstacles to ratification remain, above all the US Congress. At best, the agreement could come into force in 2017.

The TPP will incorporate Vietnam into the global value-added chain to a greater extent than previously. The TPP states represent 40 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and 30 percent of the world’s trade volume. For Vietnam, they comprise important markets, among them the US, Japan, Canada, and Australia. As in the case of the EU, Vietnam’s most important export products for which tariff reductions will be introduced are electronics, clothing, shoes, and seafood. The rules of origin, however, are stricter than in Vietnam’s agreement with the EU. One question is how much of the approximately USD 400 million paid every year by American fashion brands in import duties will actually reach female workers in the manufacturing countries. Moreover, the agreements will not only reduce duties, but will also dismantle non-tariff trade barriers and allow companies from contracting countries to join bidding in public procurement in Vietnam.

Hopes for growth and employment through Vietnam’s integration into the world market

The Vietnamese leadership expects major economic advantages to accrue in the wake of these free trade agreements. The EU and the US are already Vietnam’s biggest export markets, and its trade balance with them is positive, unlike with China. In regard to production and employment, there will be shifts from economic sectors with dwindling or no competitive advantages (e.g., in agriculture) towards areas of competitive advantage, such as labor costs - wages in Vietnam are some two-thirds lower than those in China - especially in the electronics and clothing industries, where Vietnam has an additional geographical advantage compared with competitor countries, such as Cambodia and Bangladesh, given its favorable location.

In the event of ratification of the trade agreements, Vietnam would be vaulted into the top group of Asian countries in terms of its global degree of economic integration. It remains to be seen, however, whether this will in the long term lead the country into the well-known middle-income trap. Moreover, there has been no public debate in Vietnam about the risks from the lack of competitiveness of small- and medium-sized Vietnamese enterprises as well as domestic agriculture, the opening for foreign, private service providers in the healthcare sector, or the possible increase in prices for essential medicines due to longer patent protection terms.

Vietnam is supposedly the country among the TPP signatories that will benefit the most from the trade agreement. According to estimates by the World Bank, the TPP will lead to additional growth in GDP to the tune of eight percent and to net exports increasing by 17 percent over a twenty-year period.[2] The projected figures for additional growth and new jobs should be treated with caution, however, just like the forecasts for the planned Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement. What is more, to actually achieve the aforementioned competitive advantages, Vietnam must implement far-reaching institutional reforms, amongst others, by creating a state under the rule of law that harmonizes its legal framework with the agreement as well as achieving urgently needed productivity gains. Moreover, the losses in revenue due to disappearing tariffs must be compensated for at the time of an already high fiscal deficit, totaling more than six percent.

The “most progressive trade agreement in history”?

To date, many trade agreements have contained a sustainability chapter for protecting and enforcing workers’ rights, the so-called labor chapter, and comprehensive rules for climate and environmental protection. Now, the EU and the US are talking about a “new quality” in this respect. In the agreement with the EU, there is a legally binding reference to the 2012 Vietnam Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, which contains a human rights clause and rules on cooperation in securing human rights. That said, the EU leans towards an approach that tends to promote workers’ rights rather than an approach focused on sanctions. This means providing financial assistance to help Vietnam in ratifying ILO Conventions No. 87, 98 and 105 and incorporating them into national labor law. If this does not transpire, the trade agreement could ultimately be cancelled, although this has rarely happened in the past. A study requested by the European Parliament in April 2014 on the human rights aspect of the agreement with Vietnam was not conducted before the conclusion of the agreement.

The conditions insisted upon by the US within the framework of the TPP are clearly more stringent. In the labor chapter and especially in a binding side-letter to the TPP - that is, the United States - Vietnam Plan for the Enhancement of Trade and Labor Relations - Vietnam has made concessions that are surprising for a communist, one-party system, such as its assurance to ratify Conventions No. 87 (freedom of association) and No. 98 (right to collective bargaining) and to adjust its labor laws accordingly. US president Barack Obama is keen to make sure that it is the US and not China writing the rules for trade around the world. He has described the TPP as the “most progressive trade deal in history” because it would secure workers’ rights in such countries as Vietnam more than ever before.[3] Enforcement of the international convention for the protection of endangered species and compliance with measures against overfishing the seas are also linked to trade sanctions in the agreement. The Communist Party will have the last say over ratification of the deal through the Vietnamese parliament. Its passage is likely to be effected.

Both trade agreements are not only significant for the party and the government in terms of economic policy, but are also of major importance for Vietnam’s domestic and foreign policies. The target stipulated in both agreements to create equal conditions for state-owned, private Vietnamese, and foreign companies will increase pressure to modernize and presumably also privatize state-owned enterprises. Such a result is desired by important groups within the party and the government. Moreover, the agreements will integrate Vietnam to a greater extent into Western cooperative structures. In view of growing tensions with its bigger neighbor, China, this is also a desired result of the free trade agreements.

To achieve this, there is a general willingness to meet some very painful political conditions that might ultimately mean the abolition of the monopoly of the Vietnam General Confederation of Labor (VGCL). It seems, however, that long transition periods have been agreed upon in this respect. Setting up independent, company-level trade unions that would no longer have to join the VGCL will be imperative as soon as the TPP comes into force. Vietnam has a maximum of seven years after these agreements come into effect to create the corresponding legal prerequisites for the independent unions to be able to set up industrial and subsequently national federations competing with the state-run trade union. If this is not done, the US could suspend the abolition of customs duties waiting to be effected for certain product groups. This would apply in particular to products from the clothing and shoe industries, tuna, and porcelain. Groups for which the customs tax is already abolished would not be affected.

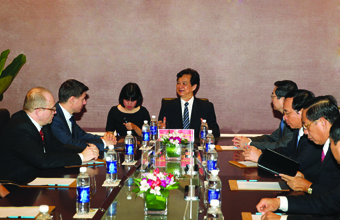

|

| President Truong Tan Sang with the leaders of the TPP member states in Manila, the Philippines __Photo: Nguyen Khang/VNA |

Hope for trade union pluralism in Vietnam?

The need to comply with the terms of the TPP exerts a great deal of pressure on the VGCL, but the leadership has already declared on several occasions that it will proactively support the concessions made by the government in the negotiations. The VGCL executive is already looking to various international experiences, for example, in Russia and Eastern Europe as well as Indonesia and Singapore, to develop a strategy that will secure the leadership role of the VGCL in an evolving labor movement environment. Thus, during the transition period, attempts will be made to find ways and means of securing the VGCL’s trade union monopoly and, above all, the financial privileges linked to it.

Joseph Stiglitz, the American Nobel Prize winner in economics, is not alone in doubting whether the EU or the US will manage to use the sustainability chapter to secure the rights of workers enshrined in the ILO’s core labor standards. It is also strongly doubted by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). From the perspective of its general secretary, Sharan Burrow, the agreement exclusively serves the interests of multinational corporations. She has said that ITUC proposals to make TPP more democratic and socially equitable have largely been disregarded and that the corresponding provisions in the labor chapter are toothless, as with other agreements. Enforcing workers’ interests by means of trade sanctions has only been attempted once, under the Central American Free Trade Agreement, against Guatemala. That case is in its seventh year, and there is still no prospect that the Guatemalan government will rectify the shortfalls.[4]

Vietnam has indeed made concessions in the TPP agreement regarding workers’ rights, but the party and the government will hardly change the existing political system. Yet from the point of view of the European trade unions, it is today worth supporting the modernizing forces that exist in the Vietnamese trade union confederation and that want to achieve more democratic labor relations in a proactive manner and without the pressure of withdrawing tariff preferences. In their view, the situation of workers’ rights in the US itself is not necessarily a shining example.-

7, Ba Huyen Thanh Quan | Hanoi, Vietnam | Tel.: +84 4 3 8455108 | Fax: +84 4 3 8452631