Linh Dang, the Olympia School, Hanoi, Vietnam

Uyen Nguyen, University of Law, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam

Children’s participation (rights) has been increasingly discussed since the 1990s with the existence of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Vietnam has demonstrated its efforts and commitment to integrating the principles of the CRC into its legal system. This study offers a comprehensive examination of the legal framework on children’s participation rights in Vietnam and its practice through a small-scale survey conducted with about 500 children aged between 16 years and 17 years to examine their experiences of children’s participation in decision-making at home, in school and in community.

Legal recognition of children’s participation rights in Vietnam

The 2013 Constitution of Vietnam (the Constitution), the highest legal document in the system of legal regulations of the country, acknowledges children's participation rights as follows: "Children shall be protected, cared for, and educated by the State, families, and society; they shall participate in issues concerning children..." (Article 37). The Constitution serves as a guideline for the State to formulate and enact other laws, including the 2016 Law on Children. Vietnam has renamed the Law on Child Protection, Care, and Education as the Law on Children, with the aim to demonstrate a broader scope of children's rights and their position within the legal system as subjects of rights, rather than merely recipients of protection and care. While the title "Law on Children" might suggest that its provisions primarily concern children as the subjects of rights, Article 3 of the 2016 Law on Children (the Law) expands its scope considerably, stating that subjects of application of this Law include “State agencies, political organizations, socio-political organizations, socio-political-professional organizations, social organizations, socio-professional organizations, economic organizations, public service units, armed forces units, education institutions, families, Vietnamese citizens; international organizations, foreign organizations operating within the territory of Vietnam, and individuals who are foreign residents in Vietnam.”

Furthermore, children's participation rights are outlined in the Law, specifically: Freedom of belief and religion (Article 19); Right to privacy (Article 21); Right to protection in legal proceedings and administrative violation handling (Article 30); Right to access information and participate in social activities (Article 33); Right to express opinions and peaceful assembly (Article 34); Ensuring information and communication for children (Article 46); and Children participating in matters affecting children (Chapter V). Essentially, it can be seen that the provisions regarding participation rights are relatively comprehensive compared to the provisions of the CRC. However, some still lack clarity and specificity, particularly in their legal implications.

Firstly, Article 34 of the Law stipulates: "Children have the right to express their opinions and desires concerning issues related to children; they are free to assemble in accordance with law as appropriate to their age, maturity, and development; they are entitled to have their legitimate opinions and desires listened to, understood, and responded to by authorities, organizations, education institutions, families, and individuals." Meanwhile, it is stated in Article 12.1 of the CRC: “States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.”

It can be observed that the separation of the two ideas in Article 34, "Children have the right to express their opinions and desires concerning issues related to children" and "Children are entitled to have their legitimate opinions and desires listened to, understood, and responded to by authorities, organizations, education institutions, families, and individuals," are likely to reduce attention and emphasis on the need to duly consider children's views. Furthermore, while Article 12 of the CRC uses the phrase "given due weight," which implies "given appropriate consideration," Article 34 of the Law uses the phrase "legitimate opinions and desires”. In the authors’ opinion, the word “legitimate” would be replaced with the word “appropriate” as it seems to align better with the phrase "given due weight" and carries a higher legal significance, emphasizing the role of adults in meeting the needs and desires of children. This stresses the importance of valuing children's viewpoints, rather than requiring them to justify their needs in order to be heard.

While Article 12.2 of the CRC emphasizes children's participation in judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child, Article 34 of the Law does not mention this aspect. Instead, the right to participate in judicial proceedings is addressed separately in Article 30 of the Law: "Children have the right to be protected in legal proceedings and administrative violation handling; the right to defense and self-defense, and protection of their lawful rights and interests; to receive legal aid, to express their opinions, and not to be deprived of liberty unlawfully; not to be tortured, maltreated, humiliated, insulted in honor, dignity, physical integrity, or subjected to psychological pressure and other forms of maltreatment."

The phrase "For this purpose" in Article 2.2 of the CRC is based on the principle stated in Article 2.1 that children not only have the right to freely express their own opinions but also have these opinions duly considered in legal proceedings. This emphasizes the responsibility of the involved parties in legal proceedings because children cannot present their opinions independently, and these opinions would hold no legal significance if they were not considered and deliberated by the responsible parties. Hence, the provisions of Articles 30 and 34 of the Law are not yet clear and legally binding the responsibilities of the involved parties in guaranteeing children's right to express their opinions.

In addition, Article 74.1 of the Law provides matters in which children may participate, including: formulation of programs, policies, legal documents, and development master plans and plans; decisions, programs and activities of socio-political organizations, social organizations and socio-professional organizations; decisions and activities of schools, education institutions, and child protection service providers; and child care, nurturing, and protection measures of families. However, the Law fails to clearly address children's right to participate in legal proceedings related to children, especially such issues as adoption, divorce, and custody rights.

Other rights such as access to information and freedom of assembly lack clear definition and guidance, particularly limitations in the exercise of these rights compared to the CRC for reasons of security, peace, etc. Additionally, the right to freedom of religion, as outlined in Article 19 of the Law, does not adequately address parental guidance in their children's religious practices.

The Law, along with Government Decree 56/2017/ND-CP, provides detailed provisions regarding the responsibilities of entities (agencies, organizations, education institutions, families, and individuals) in ensuring the implementation of children's participation rights. However, this does not offer specific instructions and explanations for cases in which children's participation rights are not properly exercised "for the best interests of the child." The failure to mention "what constitutes the best interests of the child" or "alternative measures" could easily lead to abuse by authorities. In General Comment No. 14 (2013), the Committee on the Rights of the Child (the Committee) emphasized the complementary nature of the rights protected under Articles 3 and 12 of the CRC: "Article 3.1 cannot be effectively applied if the requirements of Article 12 are not met. Similarly, Article 3.1 reinforces the function of Article 12 by facilitating the essential role of children in all decisions affecting their lives. Articles 3 and 12 must be understood together in the sense that the most effective means of determining “the best interests of the child” is actively listening to the child's perspective."

In fact, the Committee has declared that Article 3 of the CRC "In all actions concerning children …, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” However, in doing so, States must ensure that those responsible for these actions must listen to children as required by Article 12 of the CRC. In essence, while Articles 3 and 12 of the CRC may seem to conflict on the surface, in reality, the principle of "the best interests of the child" cannot be applied if listening to children under Article 12 of the CRC is not adhered to.

Children’s experiences of participation in decision-making at home, in school and in community

The study conducted a small survey at two high schools in Hanoi (the Capital of Vietnam). The convenience sampling method was used to reduce the difficulties due to resource limitations. The number of survey participants included 517 students/ children aged 16 and 17, of which 50.5 percent were boys, 44.3 percent were girls and 5.2 percent of students did not share their gender.

Children’s understanding of children’s rights:

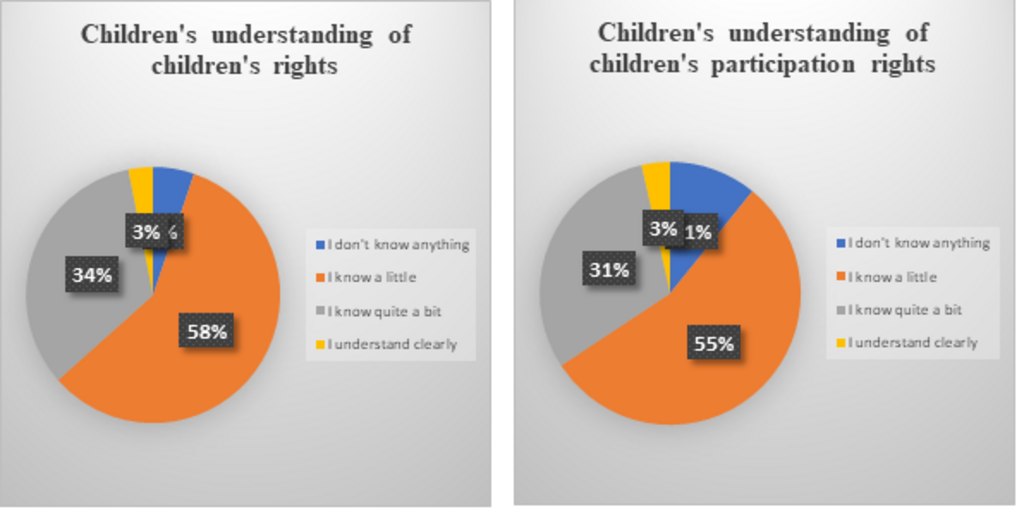

|

As shown in the graphs, the majority of children participating in this study admitted that they know little about their rights, especially the participation rights of children. The knowledge about children’s rights they receive mostly comes from their lessons at school, followed by that learned through their parents and rarely from the community where they live.

Children’s experiences of participation at home

In this study, types of children’s participation at home include discussions about important family decisions; children’s choices related school subjects; school or university selection; disciplines; recreational and extra-curricular activities; and children’s future choices such as career path. The majority of respondents indicated that they are “sometimes” involved by their parents in discussions about these decisions, from choosing subjects they want to study to more significant family decisions like house moving. Children also “sometimes” or “rarely” are shared by their parents about their rights including the participation’s rights. When their wishes or views conflict with their parents’ decisions, they seldom receive explanation from their parents. Below are some voices of the respondents:

- Please do not control children too much,

- Parents should create an environment where children have more opportunities to open up and share their thoughts,

- Parents should listen to their children’s opinions and put themselves in their children’s shoes,

- Parents should guide and share more about children’s rights,

- I wish my parents do not put too much burden on my academic performance and listen to me more.

Children’s experiences of participation in school

The respondents expressed that they do not have many opportunities to share their opinions or views on issues related to classroom and school rules; lectures’ content sand teaching methods of teachers; and school extracurricular activities:

- I want to have more activities at school to learn about children’s participation rights and I hope that our teachers/schools listen to our opinions, desires and perceive them objectively rather than imposing rules too strictly.

- Students should be equipped with the necessary skills such as soft skills to be able to exercise their participation’s rights.

Some participants do not know how to send their complaints or when they have opinions, the main way is telling the teachers; however, the participants responded that they seldom receive response from the teachers or the school (58 percent of the respondents):

- The teachers should actively listen to our thoughts and respond to our views or complaints.

- I believe the schools need to prioritize children’s right more, listen and understand children.

Children’s experiences of participation in community

In this study, the community is where children receive the least opportunity to participate in decision-making process. When asked if they had ever been involved in a meeting or event in their community to discuss issues affecting themselves, such as the construction or replacement of libraries, playground or the contribution to neighborhood policies, etc., 31.7 percent of the respondents said they were rarely asked for their views, and 30.4 percent said they had never been asked:

- There should be more events or activities to promote participation rights of children.

- I think the authority should create communication channels/procedures for children to send their opinions or in case we have complaints.

- Local authorities should widely disseminate children’s rights so that we can be aware of our entitlements.

Worthy of note, 56.7 percent of the respondents are unaware of any communication procedures for them to send their views or complaints while 24 percent of the respondents declared that their neighborhood does not offer that.

Challenges in implementation of children’s participation rights in Vietnam

Traditional customs and culture

In Vietnam, it is observed that the concept of parenthood is heavily influenced by Confucian traditions. Confucianism often idealizes parental authority and emphasizes children's obligations to a large extent. This acts like an invisible thread binding children to their parental roles, depriving them of rights that all young individuals deserve. Nowadays, although ideologies imposed on children in Vietnam are gradually being eradicated, in many families, especially in rural areas, children are still often pressured by their parents on matters ranging from education and career choice to marriage and having children. The emphasis on "filial piety" and the obligation to "obey" not only cause parents or other family members to forget their own duties and fail to listen to the opinions of children but also render children passive, only following their parents' opinions or not daring to voice their own opinions. This can be considered one of the biggest barriers to implementing participation rights in Vietnam because children's participation practices start with the smallest things right within the family. Changing perceptions and viewpoints require efforts from all stakeholders, not only the community and the state but also schools, families, and children themselves.

Economic and social situation

The economic and social situation deeply affects guaranteeing children's participation rights. Primarily, a nation’s economic situation can directly impact the ability and opportunities for children to engage in activities, decisions, and programs relevant to their lives and future. As of 2020, Vietnam still had about four million children lacking access to at least two of the basic social services, including education, healthcare, nutrition, housing, clean water and sanitation, information, social integration, and protection. Over half of the ethnic minority children in Vietnam face multidimensional poverty (Gromada et al., 2020). Urbanization is occurring at a rapid pace, and climate change, disasters, and epidemics exacerbate this situation even further. The most vulnerable children are also the ones most severely affected, as they are already at high risk due to malnutrition, inadequate access to clean water, poor sanitation conditions, lack of quality education, and limited opportunities for skills development.

Furthermore, the parents of these children often lack stable employment in the informal sector, leaving the children without the care and guidance from their parents. In some underdeveloped areas, children are often forced out of their childhood life to become the main breadwinners to support their families. Due to economic difficulties and a lack of employment opportunities for adults, they have to join the workforce very early, often in agriculture or manual labor. Children's participation in labor may restrict their time and their rights to participate in other social activities. The International Labor Organization (ILO) reports that child labor remains a significant concern in Vietnam. "58.8 percent of working children in Vietnam are child laborers. They engage in illegal work for their age, exceed the allowable working hours, or perform tasks unsuitable for their age."

Most importantly, ensuring rights relies on legal policies and support from the Government. The State, as the top-level structure, is influenced by the underlying infrastructure. Economic development and economic landscape create the necessary foundations and favorable conditions for the State to carry out its activities, including safeguarding the human rights of children. Clearly, the State requires economic resources in terms of infrastructure, transportation, technological equipment, especially in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, to adapt to new changes and global developments in guaranteeing human rights as well as children's participation rights. This includes providing equipment and information technology applications to serve everyone, including children; digitizing information, using connectivity applications to help children access information and policies easily; expressing their opinions, recommendations; or reporting, lodging complaints about rights violations.

Additionally, there remains limited understanding of the laws regarding children's participation rights in society. Due to their unique characteristics and needs, children require the support and guidance of adults to effectively exercise their participation rights. It's not just children; adults, especially parents or guardians, must understand children's participation rights as per relevant conventions and laws. Children can only participate effectively when adults respect and uphold their rights. Children need to be guided and educated about their participation rights and how to exercise them. However, many parents often lack knowledge about children's rights. They may mistakenly believe that providing material necessities is sufficient, overlooking the importance of respecting children's opinions and involving them in decision-making processes

Conclusion

Vietnam has made commendable strides in enshrining children’s participation rights in legal system, aligning with the principles in the CRC. The ratification of the CRC and incorporation of children’s participation rights into Vietnam’s Constitution and the 2016 Law on Children have demonstrated the Vietnamese Government’s commitment to promoting and protecting children’s rights, including the rights to participation of children in all matters affecting them. It can be seen that not only do gaps exist within the legal framework, but also between the law and its practice. Children still do not fully understand their rights including participation’s rights. At the same time, children are not yet given enough opportunities to be involved in decision-making processes at home, in school and in the community. One major barrier is the prevailing cultural norms and attitude that often prioritize adult decision-making over children’s views. Other factors, including political institution, economic and social situation, are also likely to hinder the implementation of children’s participation rights in Vietnam.-

REFERENCES

Gromada, A., Richardson, D., & Rees, G. (2020). Childcare in a global crisis: The impact of COVID-19 on work and family life. UNICEF. Office of Research.

Hodgkin, R., & UNICEF (Eds.). (2007). Implementation Handbook for the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Fully rev. 3. ed). Unicef.

James, A., & James, A. L. (2001). Childhood: Toward a Theory of Continuity and Change. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 575, 25-37. JSTOR.

Jenks, C. (2013). Childhood (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203023488.

Lundy, L. (2007). "Voice" is not enough: Conceptualizing Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927-942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033.

Nordenfors, M. (2012). Participation - On the children’s own terms? City of Gothenburg, Tryggare och mänskligare Göteborg.

Todres, J., & King, S. M. (2020). The Oxford handbook of children’s rights law. Oxford university press.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2009). General Comment No. 12 (2009): The right of the child to be heard, CRC/C/GC/12.

Woodhouse, B. B. (2000). Children’s Rights. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.234180.

Wyness, M. (2013). Children’s participation and intergenerational dialogue: Bringing adults back into the analysis. Childhood, 20(4), 429-442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568212459775.