Associate Prof. Dr. Nguyen Thi Viet Huong

Institute of State and Law, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences

In the course of its long history of many ups and downs, Cochin-China (Southern Vietnam) has seen different organizational forms of administration as well as legal regimes. Historical circumstances and rulers’ will in different historical periods have created the identity of politico-legal civilization of this region. This identity has led to various traditions in the conduct of the administration and people in politico-legal life, which are analyzed below:

The current demarcation of land boundaries of southern administrative units bears historical imprints

From the Nguyen dynasty, Cochin-China was divided into provinces. Under the French rule, it had 20 provinces, including Sai Gon and Cho Lon cities which were equivalent to provinces. Nowadays, southern Vietnam is divided into 19 provincial-level administrative units, including 17 provinces and two centrally run cities of Can Tho and Ho Chi Minh.

So, the number of current administrative units is almost equivalent to that of administrative units under the French rule. Yet, what is important is that the current provincial-level administrative units have been basically established on land areas similar to the former provinces, based on geographical, demographic, cultural and other factors. For instance, the present-day Ba Ria-Vung Tau province lies completely within the land boundary of Phuoc An district of Bien Hoa province in the 19th century (1836), which was also Ba Ria arrondissement (1865), Ba Ria province, and Cap Saint Jacques city (1900), Phuoc Tuy province (1956). From seven cantons of former Ba Ria province and Cap Saint Jacques city (1900), the present-day Ba Ria-Vung Tau province is divided into eight district-level administrative units, including Vung Tau city, which basically lie within the same boundaries of the former cantons.

The historical traces in the division of administrative units are also manifest in the establishment of current grassroots administrative units, namely communes, which basically retain their former land areas. More importantly, ethnic groups and the approach of social management based on ethnic groups are two factors that still leave certain imprints on the structure of current grassroots administrative units. In the past as well as at present, these factors have created both positive and negative effects, preventing religious-ethnic conflicts on the one hand and consolidating social groups in terms of customary laws and practices on the other hand, which presents a cultural obstacle to cultivating the sense of law observance for building a civic society.

Dynamism, flexibility and accessibility are historical characters inherited by present-day southern administrations

Reality shows that southern administrations at different levels are always inclined to dynamism and flexibility in administering their local affairs. These characters are the outcome of a variety of factors, of which traditions are an influential one.

Due to objective and subjective historical conditions, southern administrations at different levels often enjoyed relative independence and certain autonomy in state administration activities. The regional complexities, the swift historical changes, the geographical distance from the center and the loose management by the central administration prompted southern administrations to decide by themselves many issues before receiving official instructions from the central government and allowed them to apply in a more casual manner rules on the performance of official duties.

Moreover, given the context that they had to manage a vast territory mainly reclaimed by various ethnic groups and a highly adaptable population, especially poor peasants living in open-structured villages and communes, the southern administrations at different levels became gradually accustomed to a mechanism of favorable relationship with people.

Although the French domination in colonial Cochin-China caused many negative social consequences, prominently the political enslavement which abolished many dynamic elements of socio-political life, it brought about some democratic elements from western bourgeois democracy. These elements include the restricted application of the model of separation of three powers, the decentralization of legislative and regulatory power, the clear distinction between administrative and judicial powers, and the administrative and judicial systems’ relative independence from the political system. This helped prevent the abuse of power by state officials, a common phenomenon in the feudal regime.

The colonial political regime disallowed such popularly elected bodies as District Councils, Provincial Councils and Municipal Councils in Cochin-China to discuss political issues. It, however, gave them certain power in budget control, construction of public facilities, development of education and healthcare. Adjudication work in the judicial system was also participated to a certain extent by people.

It can be said that through the colonial state institution, the southerners saw the first rays of light of western bourgeois democracy, which became clearer with the imposition of neo-colonial political institutions in southern Vietnam by Americans for several decades later. Such historical evolution has exerted positive impacts, creating democratic practices in activities of state agencies and civil servants as well as easy accessibility to state agencies for citizens.

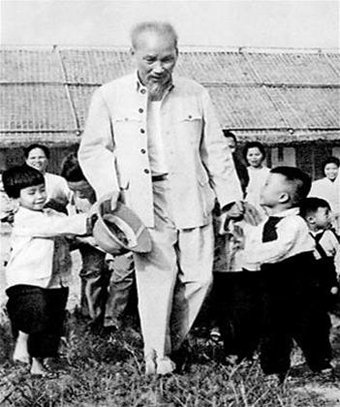

|

| Nguyen dynasty’s mandarins in Hue imperial city in the late 19th century __Photo: https://vi.wikipedia.org |

The swift responsiveness of contemporary southern administrations to “doi moi” (renewal) is a positive consequence of their organizational history

An obvious feature in the performance of current southern administrations at different levels is their swift responsiveness to new politico-legal events and situations. They always take the lead in implementing renewal requirements and propose many new renewal ideas from their practical activities, such as reforming administrative procedures according to the one-stop-shop mechanism, promoting the supervision of socio-political organizations over the organization and operation of Party and State bodies, advancing the adversarial system and bringing into play the role of lawyers.

History shows that the organization of southern administrations was always accommodated to upheavals of the politico-legal life simultaneously with the process of open exchange with the politico-legal cultures in other regions. Being established in a new land, the administrations were usually organized on an experimental basis and step by step improved as the land area and population became more stable. In other words, the administrative units as well as administrations here always show a certain level of openness, ready to accept new elements.

It should be further stressed that Cochin-China witnessed the involvement of many exotic politico-legal elements due to the presence of some foreign political forces. When participating in the region’s politico-legal life, these forces integrated themselves fairly well thanks to the high adaptability of the vast majority of local population. Such high adaptability, in its turn, was the outcome of the living conditions and ruling military-civilian model applied by rulers. As far as this aspect is concerned, it can be easily realized that the responsiveness to renewal is not only the potential but also the real character of southern administrations at different levels.

In reality, the openness, responsiveness to renewal, and non-conservatism in the organizational and operational traditions of southern administrations were made the most of by feudal as well as colonial states in experimenting their ruling policies and measures. For instance, the organizational form of semi-military administration in southern Vietnam during the reign of Nguyen Lords became the model of national administration during the initial period of the Nguyen dynasty, and Cochin-China was chosen by the French colonialists for the first administrative reform and the application of western bourgeois democratic institutions. This reality can be seen as a historical lesson for the selection of geographical areas for application of experimental policies and measures in the organization and operation of present-day administrations in Vietnam.

The professional management skills of present-day southern administrations are attributed to historical elements

As southern Vietnam’s administrations at different levels went through a long period of self-management of vast areas inhabited by people from various social strata while having to perform their obligations towards the central administration and defend their territories, they were tempered with rich experiences in building and managing the administrative apparatus. Such managerial skills became more professional when the region fell into the hands of French colonialists who then enforced a modern colonial politico-legal regime.

Right in the region, various educational institutions were opened, including Thu Dau Mot Fine Arts School in 1901, Bien Hoa Fine Arts School in 1903, Gia Dinh Painting School in 1913, the Civil Engineering School in 1902 for training local civil engineers, the native medicine school in 1903 for training Vietnamese nurses and midwives, and Saigon vocational training school in 1904 for training skilled metal workers, carpenters and molders. Although these schools only aimed to train human resources for colonial exploitation, they accidentally created a contingent of intellectuals independent from the administration and a contingent of civil servants who had fairly professional skills.

In addition, a modern communications system comprising the press and telegraph was built, contributing to the collapse of the traditional system of social contact within the Vietnamese community in Cochin-China. It is, therefore, not accidental that before the August Revolution Cochin-China was the only region in Vietnam seeing a public communist movement operating in various modern forms via the parliament and press. The popularly elected bodies of a western bourgeois state were initially brought into play in disrupting the feudal legislative ideology. The relationship between people and state officials as well as between state officials saw positive changes toward greater equality. The salary and pension regime introduced for civil servants of the colonial administration before the August 1945 Revolution helped improve the sense of responsibility of these servants.

From the end of the 19th century, the Sai Gon-Cho Lon region was planned, built and managed under a regime suitable to modern cities, resulting in a gradually established order in urban life and a heightened sense of law observance among inhabitants.

The habit of acting according to feeling in social life and the practices of abusing power and acting “beyond the line” in state management in southern Vietnam are more common than elsewhere in the country, manifesting negative historical vestiges

The first and easily noticeable manifestation of the dark side of the above-mentioned positive elements is the habit of acting according to feeling even to the extent of non-observance of law among a portion of southerners. This can be explained by the special living environment in this region.

Before the region’s reclamation, native inhabitants lived in a vast geographical and social space and adopted a liberal way of living without imposed regulations and institutions. Migrating to the southern delta in the late 17th century, the first migrants of Viet group, followed by Cham, Hoa and Khmer groups, brought along different cultures and experiences in social organization. Such cultures and experiences were reconciled in the process of land reclamation. In this process, individuals who had physical strength, courage, a sense of unity and organizational capability rose to become leaders in the reclamation of an area and semi-official representatives of inhabitants there. The chivalrous and magnanimous nature of these free migrants was developed and preserved in a political environment that lacked strict rules but arbitrary decisions of rulers.

Therefore, the southerners are characterized by broad-mindedness and dynamism, which always present two sides of a coin. Negatively, these are always potential reasons for divorce from legal institutions. The military-civilian regime lasting from the late 17th century to 1832 and the wars from 1833 to the end of the 19th century made the southerners, particularly men, of many generations live a half-civilian-half-military life in difficult circumstances, thus cultivating in them a high adaptability. Similarly, the commodity agricultural economy based on massive land reclamation from the late 19th century made villages and communes, especially in the west of the region, during the French rule, adopt an open structure, giving their inhabitants, especially poor farmers, a new space for social contact and livelihood.

Because of the prolonged existence of the “semi-military” administration that vested greater powers in army generals and the lax control of the region by the central administration, abuse of power, neglect of discipline and action according to feeling were found even among state officials.

For more than a century before 1802, southern Vietnam had been divided into provinces, districts and hamlets, all controlled by army generals. The grassroots administrative units had been loosely managed. It was very common that peasants in one hamlet could till the land in others and inhabitants in one district could pay tax in others. Until 1788 when Nguyen Anh took power, this situation was more or less remedied but by 1832 the southern administrations were still simply organized and led by military commanders.

The colonial administration founded in Cochin-China remained to be a heavily military apparatus where most leading officials were once generals of the expeditionary army. It should be further pointed out that when southern Vietnam was ruled by the Nguyen Lords, the autonomy regime was applied to localities, under which the local chiefs held all powers. This regime, together with the self-management regime in communes and villages or equivalent units during the French domination period, hindered the local population’s connection with the state, even created social institutions different from the common institutions of the Vietnamese community in the region. For example, the regulations on management of Hoa (Chinese) minority people obstructed them from complete integration into the Vietnamese community in all economic, cultural and social aspects.

To overcome the negative aspects and promote the positive ones in the organization of southern administrations, a system of comprehensive educational, legal and organizational solutions should be implemented. It is also necessary to increase southerners’ mastery, law awareness and observance as well as their accessibility to administrations.-