Freedom of movement is among the fundamental rights under the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to which Vietnam has been a member state since 1982. Freedom of movement not only creates the premise for an individual to enjoy civil, political, and other economic, social and cultural rights, but also as a condition to promote the development of the economy and society of countries. Nonetheless, the right to freedom of movement is not absolute and can be subjected to restrictions in certain circumstances. The following article examines the regulations on restrictions on freedom of movement following the ICCPR and Vietnam’s law, and evaluates the practical implementation as well as the shortcomings of the restrictions amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dang Linh Chi

Department of International Law

Ministry of Justice

Freedom of movement and its restrictions under the ICCPR

Article 12 of the ICCPR affirms the two main components of freedom of movement, including: (i) an internal aspect, relating to freedom of movement within a country, i.e., “Everyone lawfully within the territory of a State shall, within that territory, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose his residence”[1] and (ii) an external aspect comprising freedom of movement between States, i.e. the rights to leave one’s country[2] and the right to enter one’s “own country”[3]. It can be seen that, according to the ICCPR, the subject of freedom of movement comprises all citizens, including foreigners. Thus, a foreigner living or lawfully present in a country also has the right to freely move within the territory of that country without being obstructed.

Nevertheless, Article 12.3 of the ICCPR also specifies that the right to freedom of movement and residence is not an absolute right, as it may be subject to certain restrictions depending on the law of a member state. Specifically, the right to freedom of movement shall not be subject to any restrictions except those provided by law for the purpose of protecting national security, public order, public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others, and be consistent with the other rights recognized in the ICCPR.

To provide guidance for governments on the limitation of rights, in 1984, the United Nations Economic and Social Council adopted “The Siracusa Principles on the limitation and derogation provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights”. According to Part I of these Principles, the requirements for limitations under the ICCPR can be summarized as follows: (i) Any measures shall be provided for by law and be compatible with the object and purposes of the ICCPR; (ii) None of the restrictions imposed must discriminate in violation of international human rights law; (iii) Any such measures should also meet strict requirements, including legality, necessity and proportionality; and (iv) All limitations shall be applied in a non-arbitrary manner and in favor of the rights at issue.

It is also noteworthy that any such measures should be of a defined duration and in the interest of protecting public health. For further interpretation, CCPR General Comment No. 27 (adopted at the Sixty-seventh session of the Human Rights Committee, on November 2, 1999) also indicates that: “The permissible limitations which may be imposed on the rights protected under Article 12 must not nullify the principle of liberty of movement, and are governed by the requirement of necessity provided for in Article 12, paragraph 3, and by the need for consistency with the other rights recognized in the Covenant”.[4]

|

| A frontline medical worker is going to get COVID-19 vaccination in Dong Hoi General Hospital, Quang Binh province__Photo: Vo Dung/VNA |

Freedom of movement and its restrictions under Vietnam’s law

Article 23 of Vietnam’s 2013 Constitution states that: “Citizens have the right to free movement and residence within the country, and the right to leave the country and to return home from abroad. The exercise of those rights shall be prescribed by law”. Furthermore, the Constitution emphasizes that the “lives, property, rights and legitimate interests” of foreigners residing in the country, including the right to freedom of movement, shall be protected by the Vietnamese law.[5]

These constitutional principles are specified in a number of relevant specialized laws, including the 2015 Civil Code, the 2019 Law on Entry and Exit of Vietnamese Citizens, the 2014 Law on Entry, Exit, Transit and Residence of Foreigners in Vietnam (as amended and supplemented in 2019), the 2006 Law on Residence (as amended and supplemented in 2013), among others. In the event of an infectious disease, in addition to medical measures, the 2007 Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases also allows the Head of the Steering Committee for Disease Control to apply administrative measures to limit the spread of diseases, such as isolation and medical quarantine upon entry and exit from class A-epidemic zones.[6]

For Vietnamese citizens, the exercise of freedom of movement is clearly stipulated in the 2019 Law on Exit and Entry of Vietnamese Citizens. Accordingly, immigration dossiers include diplomatic passports, official passports, ordinary passports and laissez passer. In particular, Vietnamese citizens are ineligible for immigration documents in the following cases[7]:

(i) Those failing to comply with decisions on sanctions of against administrative violations specified in Clauses 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 or 7, Article 4 of this Law.

(ii) Those suspended from leaving the country, except for the cases specified in Clause 12, Article 37 of this Law.

(iii) Those influencing national defense and security according to decisions of the Minister of National Defense or Minister of Public Security.

In addition, Article 36.8 of the Law also indicates the suspension of exit for persons who contract dangerous and infectious diseases to prevent the epidemic from spreading to the community, unless allowed by foreign authorities for entry.

For foreigners, the conditions for their entry are stipulated in Article 21 of the 2014 Law on Entry, Exit, Transit and Residence of Foreigners in Vietnam. Accordingly, a foreigner may enter the country when he holds a passport or an international travel document and a valid visa (except those eligible for visa exemption), provided that he neither falls into the cases of entry refusal nor is subject to entry suspension as specified in Article 21 of this Law, including “for the reasons of national defense, public security, and social order and safety”.

Regarding exit, a foreigner may leave Vietnam if he or she (i) holds a passport/laissez-passer; (ii) has a valid temporary residence permit, temporary residence card or permanent residence card; (iii) and is not suspended from exit as prescribed in Article 28 of this Law.[8] Of note, the Law also indicates that a foreigner may not be allowed to enter Vietnam for the purposes of epidemic prevention and control.[9]

In addition to the above regulations, the 2007 Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases also specifies medical isolation and quarantine on entry and exit from class-A epidemic zones, in particular:

- Isolation is mandatory for persons suffering from an epidemic disease, persons suspected of suffering from an epidemic disease, persons carrying epidemic pathogens, persons having been in contact with pathogens of an epidemic disease of class A or a number of diseases of class B stipulated by the Minister of Health.[10]

- Regarding the control of entry and exit from class-A epidemic zones, the applied measures include: (i) restricting persons and vehicles from entering and leaving epidemic zones; in case of necessity, medical inspection, surveillance and disposal will be conducted; (ii) prohibiting transportation from epidemic zones of articles, animals, plants, food and other commodities capable of transmitting the epidemic disease; (iii) taking personal protection measures, for persons entering epidemic zones specified in Article 51.1 of this Law; and (iv) other necessary measures as prescribed by law. In order to effectively take the above-mentioned measures, heads of anti-epidemic steering committees will set up quarantine posts and stations at road junctions leading to epidemic zones.[11]

Assessment of the implementation of restrictions on freedom of movement in Vietnam amid the COVID-19 pandemic

It is safe to affirm that the measures taken to restrict freedom of movement in Vietnam against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic are reasonable, in line with the legality, necessity and proportionality stated in the Siracusa Principles on the limitation and derogation provisions in the ICCPR.

- With respect to the legality: As discussed above, the recent directive issued as well as the measures taken to restrict freedom of movement for the purpose of public health are not contrary to the provisions of the Constitution and relevant laws.

- With respect to the necessity: Due to the airborne transmission of virus SARS-CoV-2 with high contagious nature, the restriction of movement is of paramount importance. Thanks to the drastic and timely application of these measures since the outbreak of the pandemic, Vietnam has managed to put it under control at present. This clearly proves the necessity for measures to limit the freedom of movement for the time being.

- With respect to the proportionality: The benefits gained from the restriction of the rights in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam have on balance proven valuable and effective. In essence, restricting the right to freedom of movement is about finding a balance between personal interests and the interests of others and of the community. It can be seen that a delay in the implementation of restrictions on freedom of movement by a number of countries in favor of personal freedom has resulted in great harm to the society. Considering the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the current political, economic, legal and cultural situation in Vietnam, the measures applied are completely appropriate.

However, there is no doubt that measures taken to restrict freedom of movement in the current pandemic context have resulted in a number of negative impacts on the domestic socio-economy, as discussed below.

Negative impacts of restrictions on freedom of movement in Vietnam

Negative impacts on the economy

Tourism is one of the service industries most severely affected by the restrictions on the right to freedom of movement. The introduction of social distancing or entry restrictions for foreigners since 2020 has resulted in a significant drop in tourist arrivals. Specifically, the total number of tourists served by local accommodation establishments was only 97.3 million, down 44 percent from the previous year, while the number of tourists served by tour operators was 3,7 million, down 80.1 percent. Besides, international tourists to Vietnam decreased by 78.7 percent compared to the previous year, reaching only 3.8 million. According to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, the sharp decline in the number of domestic and international tourists has led to a significant decrease in revenue for accommodation and travel establishments, estimated at 61.8 trillion VND, down by 43.2 percent.[12] While the tourism industry has sought to implement numerous measures to stimulate domestic tourism to compensate for the loss of international tourism, this is still only considered a temporary solution to keep domestic tourism businesses operating. As estimated by McKinsey & Company Global Management Consulting, it is not until 2024 that Vietnam’s tourism industry can recover thanks to domestic tourism.

|

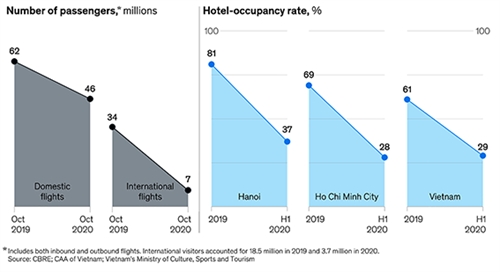

After tourism, the aviation industry has suffered the most damage due to travel restrictions. According to the Civil Aviation Administration of Vietnam, the number of passengers passing through Vietnam’s airports in 2020 decreased by nearly 44 percent compared to that of 2019. Specifically, the flight operation volume reached only 340,000 flights, a decrease of more than 31.9 percent. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) estimated that the Vietnamese market had lost about USD 4 billion in 2020 alone. In the first half of 2021, airlines only operated 19,295 flights, down more than 44 percent compared to the same period in 2020.

Negative impacts on the society

The measures taken to restrict the right to freedom of movement have negatively affected almost every service industry, which directly impacts the employment. When the demand for travel, tourism and accommodation plunges, pay cuts and employee layoffs become more common. According to a survey of the Vietnam Tourism Advisory Council, by the end of 2020, up to 18 percent of businesses had to lay off all employees; 48 percent of businesses cut 50-80 percent of their payrolls; 75 percent of businesses provided alternative forms of financial support for their unemployed workers. The Hanoi Department of Tourism also reported that the number of employees who temporarily resigned and terminated labor contracts at travel and transportation companies accounted for approximately 50-90 percent.[13] For the aviation industry, in April 2020 alone, a flight restriction decision caused Vietnam Airlines to give all employees pay cuts and have up to 50 percent of employees laid off. The 2020 salary report also shows that the pilot’s salary was slashed by more than 50 percent over the same period while the plan to increase the pilot’s regular salary was shelved. Meanwhile, the average salaries of flight attendants and ground workers were expected to decrease by nearly 48 percent and 44.5 percent respectively.[14]

The restrictions on freedom of movement also exert harmful effects on the domestic education system. At times of outbreak, all public, non-public, private schools and other educational institutions must cease face-to-face learning. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education and Training had to re-arrange exams and assessment sessions for all levels of education. Decisions were issued in 2020 to adjust the school year timetables for preschools, general education and continuing education establishments, including delaying the school closing and organization of entrance exams.[15] Although online learning platforms are considered optimal in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is difficult for ethnic minority children and those with disabilities to make full use of these learning options. [16]

Vaccine passports - Promising measure to remove restrictions on freedom of movement?

Many people around the world by now have recovered from the COVID-19 or fully vaccinated, making them to be purportedly immune to SARS-CoV-2. As a result, more and more governments are considering removing movement restrictions[17], allowing these individuals to both locally and globally travel at their will with the “vaccine passport” (also known as “immunity passport”). This “passport” serves as a proof granted by the testing authority that its bearer has antibody responses to the coronavirus, and thus is protected from a second infection.

The concept of the vaccine passport is considered a potential way to lift the restrictions on freedom of movement, recover individual well beings, permit faster economic recovery and further contribute to encouraging more people to get vaccinated against the COVID-19.

Although endorsed by many countries around the world and expected to apply in the near future, vaccine passports have not yet received full support from experts. There are still many concerns for using an immune passport, such as the possibility of infringing upon privacy, becoming an instrument of discrimination, social differentiation, etc.[18] As such, the application of vaccine passport needs to be carefully explored to minimize negative problems that may arise, especially the violation of other human rights and creating wide-ranging discrimination. In a press conference in early May, Deputy Minister of Health Tran Van Thuan revealed that the Prime Minister had instructed the Ministry of Health to work with other related ministries and sectors to find out effective methods for application of vaccine passports at appropriate time.

To date, the restrictions on freedom of movement have proven to be among the most effective methods currently applied by a majority of countries in the world to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although these restrictions give rise to some negative problems, the benefits they deliver are undeniable. Still, countries also urgently need to study other feasible measures so that citizens can fully exercise their rights to freedom of movement in the shortest time possible.-

[1] Article 12(1) of the ICCPR.[2] Article 12(2) of the ICCPR.[3] Article 12(4) of the ICCPR.[4] Paragraph 2 of CCPR General Comment No. 27.[5] Article 48 of the 2013 Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.[6] Article 53 of the 2007 Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases.[7] Article 21 of the 2019 Law on Exit and Entry of Vietnamese citizens.[8] Article 27 of the 2014 Law on Entry, Exit, Transit and Residence of foreigners in Vietnam (as amended in 2019).[9] Article 28 of the 2014 Law on Entry, Exit, Transit and Residence of foreigners in Vietnam (as amended in 2019).[10] Article 49.1 of the 2007 Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases.[11] Article 53 of the 2007 Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases.[12] Du lịch Việt Nam 2021: Rất cần quyết tâm và nỗ lực để vượt khó (Vietnam Tourism 2021: Strong determination and effort needed to overcome difficulties), Portal of the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, https://www.gso.gov.vn/du-lieu-va-so-lieu-thong-ke/2021/02/du-lich-viet-nam-2021-rat-can-quyet-tam-va-no-luc-de-vuot-kho/[13] Kết quả khảo sát thiệt hại dịch bệnh COVID-19 đối với Doanh nghiệp du lịch Việt Nam (Survey results show damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to tourism enterprises in Vietnam), Portal of the Tourism Department, Quang Ninh province,https://www.quangninh.gov.vn/So/sodulich/Trang/ChiTietTinTuc.aspx?nid=901[14] Ngành hàng không cắt giảm mạnh nhân sự để tồn tại (Aviation industry sharply cuts its staff to survive), VnEconomy e-magazine, https://vneconomy.vn/nganh-hang-khong-cat-giam-manh-nhan-su-de-ton-tai-20210308230438419.htm[15] Lùi thời gian kết thúc năm học, dời lịch thi THPT quốc gia sang tháng 8 (Vietnam delays the school closing and entrance exams to August), https://vietnamnet.vn/vn/giao-duc/goc-phu-huynh/lui-thoi-gian-ket-thuc-nam-hoc-doi-lich-thi-thpt-quoc-gia-sang-thang-8-623943.html[16] COVID-19 ảnh hưởng tiêu cực đến việc thụ hưởng quyền con người ở Việt Nam (Negative impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the enjoyment of human rights in Vietnam), Tuoitre online, https://tuoitre.vn/covid-19-anh-huong-tieu-cuc-den-viec-thu-huong-quyen-con-nguoi-o-viet-nam-20201215150916797.htm[17] Covid Vaccine Passport programs by country: Quarantine and Testing Exemptions, Universal https://www.universalweather.com/blog/covid-vaccine-passport-programs-by-country-quarantine-and-testing-exemptions/[18] Ten reasons why immunity passports are a bad idea, Nature, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01451-0