|

| Officials of the Social Security Office of Hau Giang province (now part of Can Tho city) disseminate insurance policies to a local resident__Photo: VNA |

Center for Community Support and Development Studies, Real-Time Analytics and United Nations Development Program

Introduction

As the 2024 Law on Social Insurance has come into effect from July 1, this article explores an important source of economic vulnerability - lack of access to social insurance - as captured from the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI)[1] in 2024. To further shed light on citizens’ perceptions of economic vulnerability and security, the 2024 PAPI survey explored the relationships between social insurance coverage and savings. These insights are particularly prescient given the historic government restructuring announced in late 2024 and the enactment of the 2024 Law on Social Insurance. As such, the 2024 PAPI survey findings[2] provide a baseline for decision-makers to assess the effect of the law, designed to counter the increasing numbers of workers cashing out of social insurance for one-off payments since the pandemic amid personal financial pressures. The findings can, in the future, be used to assess whether the law has its desired impact of increasing the uptake of social insurance and reducing the barriers that prevent citizens from accessing it.

Social insurance coverage: widening but unequally distributed across sectors

This section examines social insurance coverage and sectoral distribution, leveraging PAPI data collected since 2019, to evaluate preparedness for unemployment shocks. This analysis is particularly relevant for less prepared workforces in stable sectors, such as for workers in the state sector, given planned government restructuring from late 2024.[3]

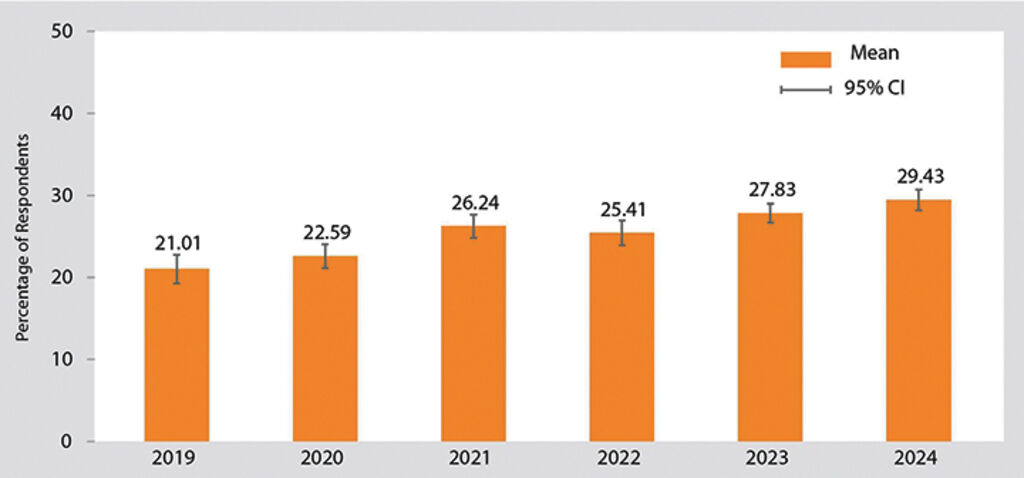

Drawing on data from PAPI surveys over time from 2019 to 2024, Figure 1 shows how social insurance coverage has slowly increased since 2019. It reveals an 8-percent increase in coverage in six years from 2019 (21.01 percent) to 2024 (29.43 percent).

|

| Figure 1: Percentage of respondents with social insurance, 2019-24 |

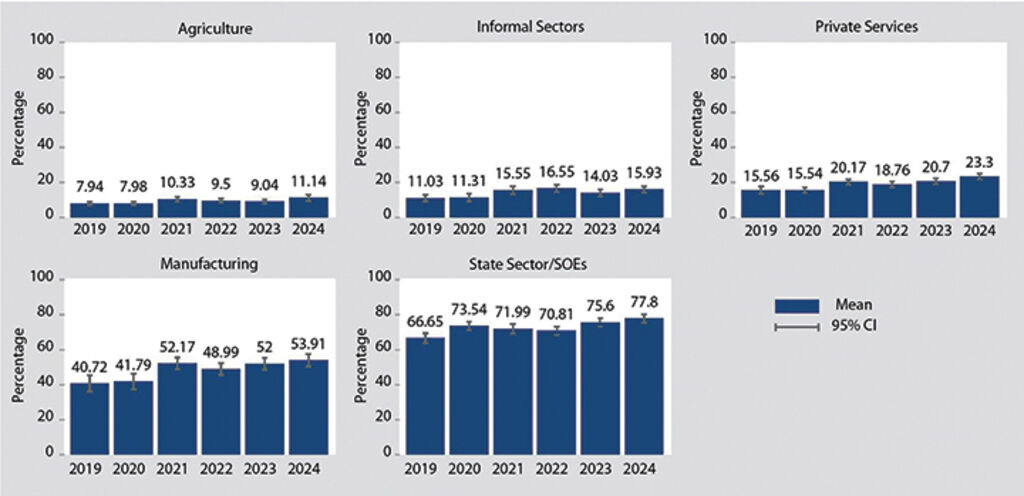

The incremental change from 2019 to 2024 is also seen in major sectors, such as agriculture, informal sectors, private services, manufacturing, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). As Figure 2 reveals, for instance, the coverage rose from 15.56 percent to 23.3 percent in private services, from 40.72 percent to 53.91 percent in the manufacturing sector, and from 66.65 percent to 77.8 percent in the state sector and SOEs over the period of six years. Some of this may be due to an increase in state and private firms complying with compulsory social insurance contributions.

|

| Figure 2: Percentage of respondents with social insurance by key employment sectors, 2019-24 |

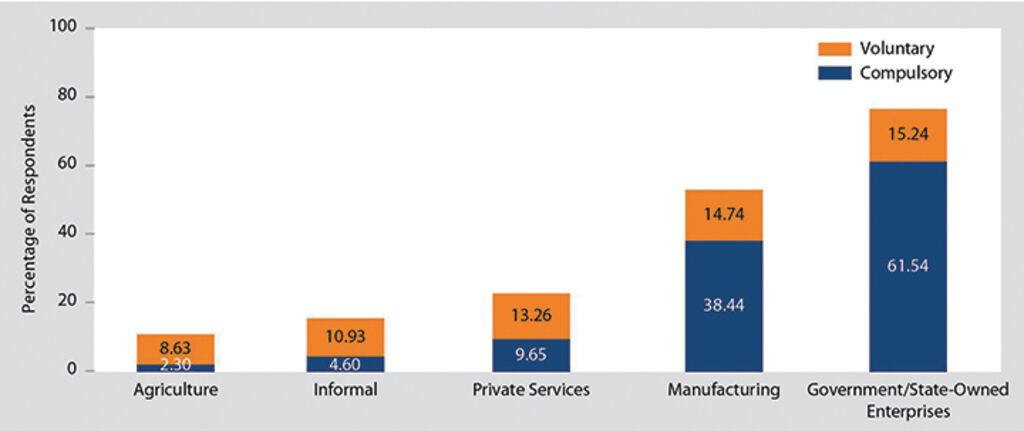

However, access to social insurance was uneven across employment sectors as captured in the PAPI surveys since 2019. Figures 3, 4 and 5 show that access to compulsory social insurance is greater, which is expected given that employment contracts are more prevalent in manufacturing and the state sector.

As presented in Figure 3, for respondents working in the state sector and SOEs, 76.78 percent reported having social insurance, with 61.54 percent covered by compulsory insurance. In manufacturing, 53.18 percent of PAPI participants reported purchasing social insurance, with 38.44 percent holding compulsory insurance. In contrast, for agriculture workers, only 10.93 percent have social insurance, with 8.63 percent buying voluntary insurance.

|

| Figure 3: Access to compulsory and voluntary social insurance by employment sector, 2024 |

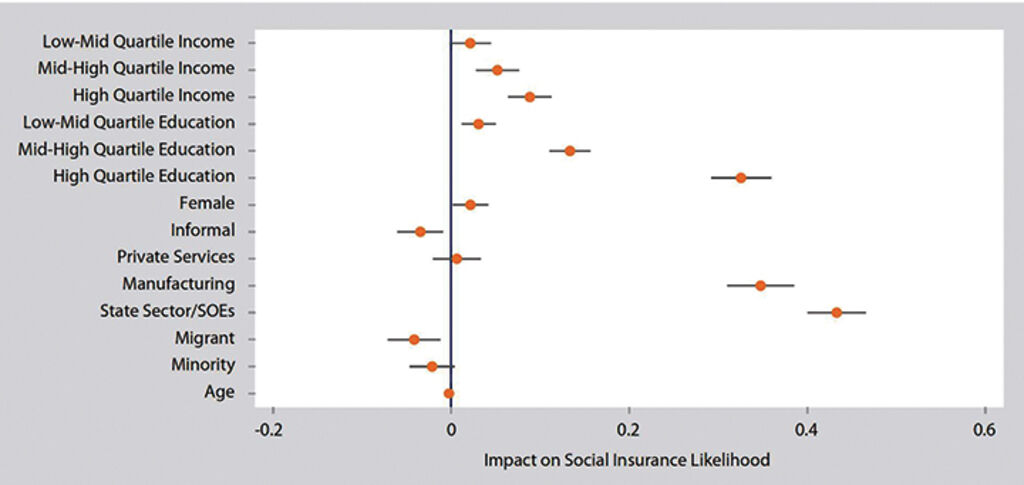

When disaggregated by levels of income, education, economic sectors, and demographic features, respondents in manufacturing, the state sector and SOEs tend to have social insurance coverage, as do those with higher education levels and income. As Figure 4 further illustrates, those working in the informal sectors and private services – the majority of workers surveyed in PAPI – do not have social insurance of any type. Moreover, migrant employees and ethnic minorities are less likely to access social insurance.

|

| Figure 4: Access to social insurance coverage by different factors, 2024 |

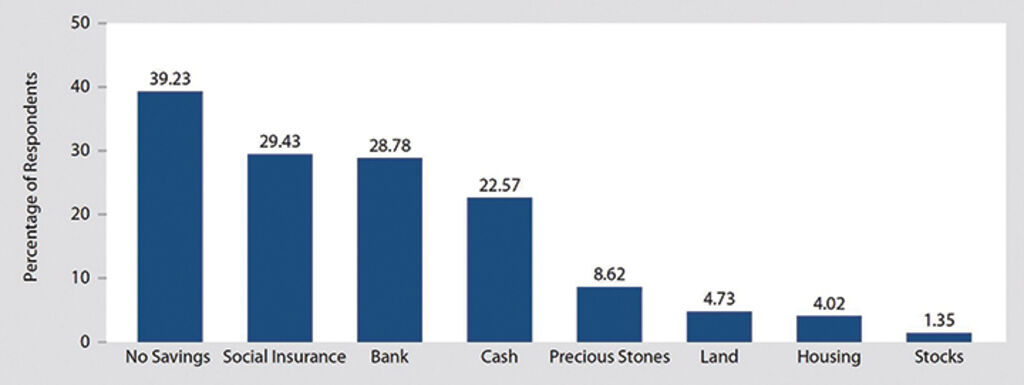

To assess whether citizens had any form of financial savings for the future, the 2024 PAPI survey explored a range of resources that citizens might tap into to maintain their livelihoods upon retirement or if unable to work. Figure 5 shows that nearly four-in-10 respondents (39.23 percent) reported no source of savings, while only 29.43 percent were utilizing social insurance as the most prevalent form of savings. The second most common form of savings is through banks (28.78 percent). This, in turn, helps explain the heightened public concern about corruption in 2024 and its linkages with the threat of high-profile fraud and corruption cases like Van Thinh Phat[4] posing a systemic threat to the banking system. More than one-fifth (22.57 percent) of respondents held savings in cash, while 8.6 percent put their savings in precious metals or stones. Although land, housing and stocks were hot investments among wealthier classes, fewer respondents could afford to save in such asset classes.

|

| Figure 5: Respondents’ sources of savings for retirement, 2024 |

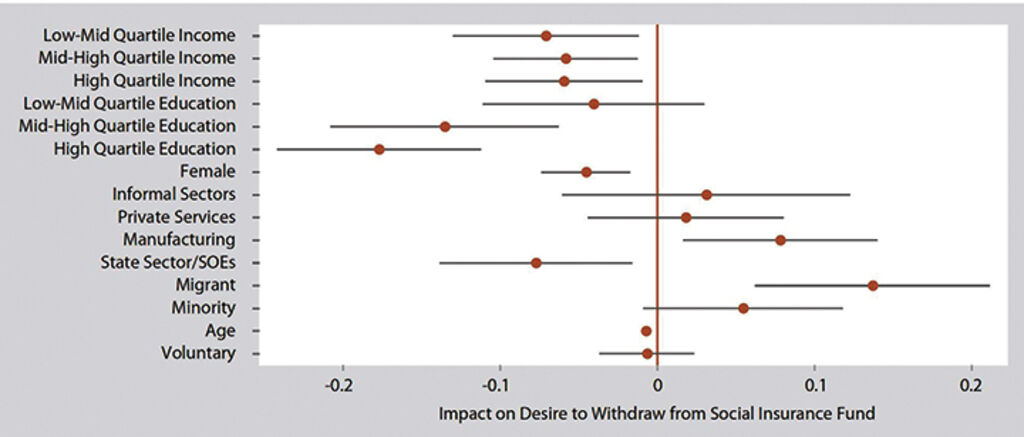

A major social insurance issue in the past five years was citizens’ desire to prematurely withdraw retirement contributions from the Social Insurance Fund, as reported by the Vietnam Social Security.[5] The 2024 PAPI survey found that 29 percent of respondents with social insurance would withdraw their contributions in a lump sum if given the opportunity.

As illustrated in Figure 6, this preference was less common among those with higher income and education level, and those employed in the state sector and SOEs. Migrants and manufacturing sector workers expressed the strongest desire for withdrawals, followed by ethnic minorities and men, who are compared to women in the graph.

|

| Figure 6: Desire to withdraw social insurance contributions by factor, 2024 |

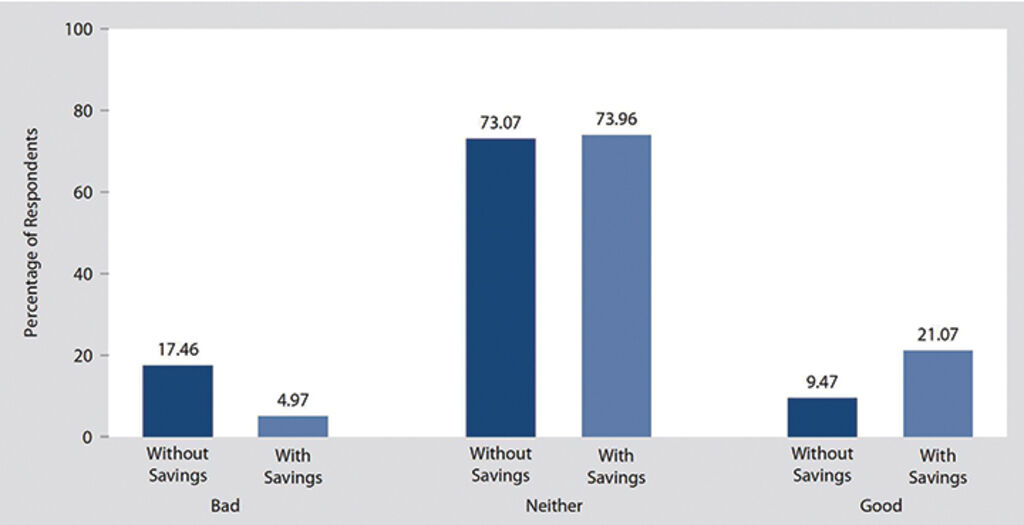

Access to social insurance and savings – a driver of citizens’ perception of economic wellbeing and issues of greatest concern

This section reveals how a lack of savings could impact citizens’ perceptions of household economic vulnerability. Figure 7 shows that among respondents with neither savings nor social insurance, 17.46 percent said their household economic situation was “bad”, four-fold higher than those with savings. Only 9.47 percent without savings said their household economic situation was “good” compared to 21.07 percent with savings. Statistical analysis shows that even when accounting for income level, economic sector, and other factors that correlate with low savings, the lack of savings still increases household economic concerns.

|

| Figure 7: Levels of citizens’ satisfaction with household economic conditions by saving status, 2024 |

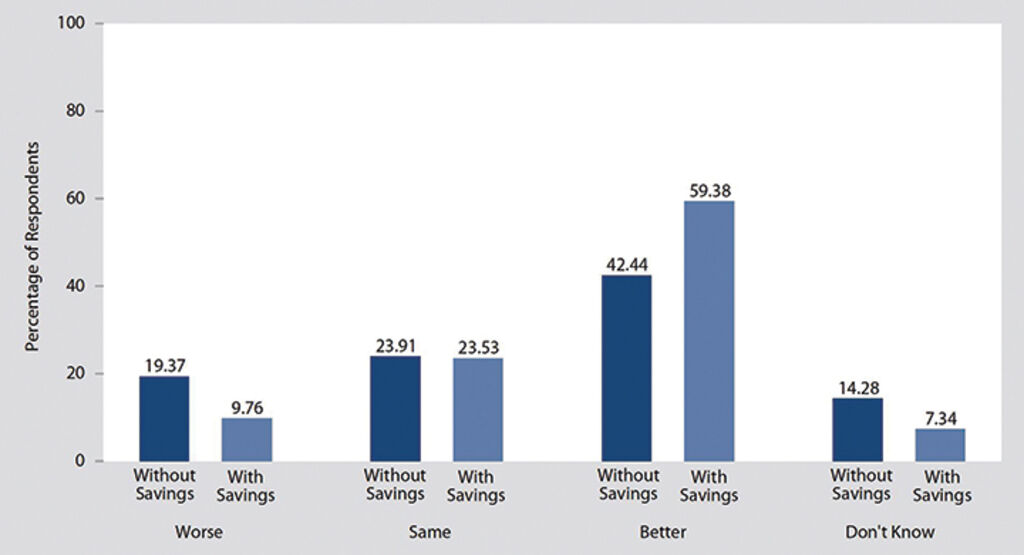

The same patterns can be seen in assessment of future household economic conditions in the next five years: with 59.38 percent of those with savings believing their economic situation would brighten, around 17 percent higher than those without savings. Figure 8 reveals such patterns.

|

| Figure 8: Levels of citizens’ confidence in future household economic conditions by saving status, 2024 |

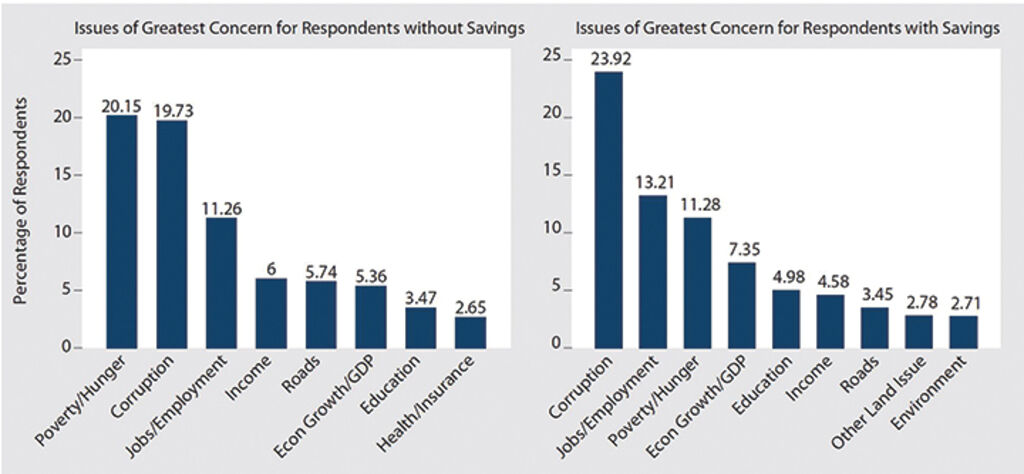

Furthermore, the lack of savings appears to influence citizens’ perception of issues of greatest concern. As shown in Figure 9, around one-in-five (20.15 percent) of those without savings are more likely to say poverty was the most important issue requiring the State’s action, compared to 11.28 percent of those with savings. Not having savings takes away from the otherwise large numbers of respondents concerned with corruption.

|

| Figure 9: Issues of greatest concern for respondents with or without savings, 2024 |

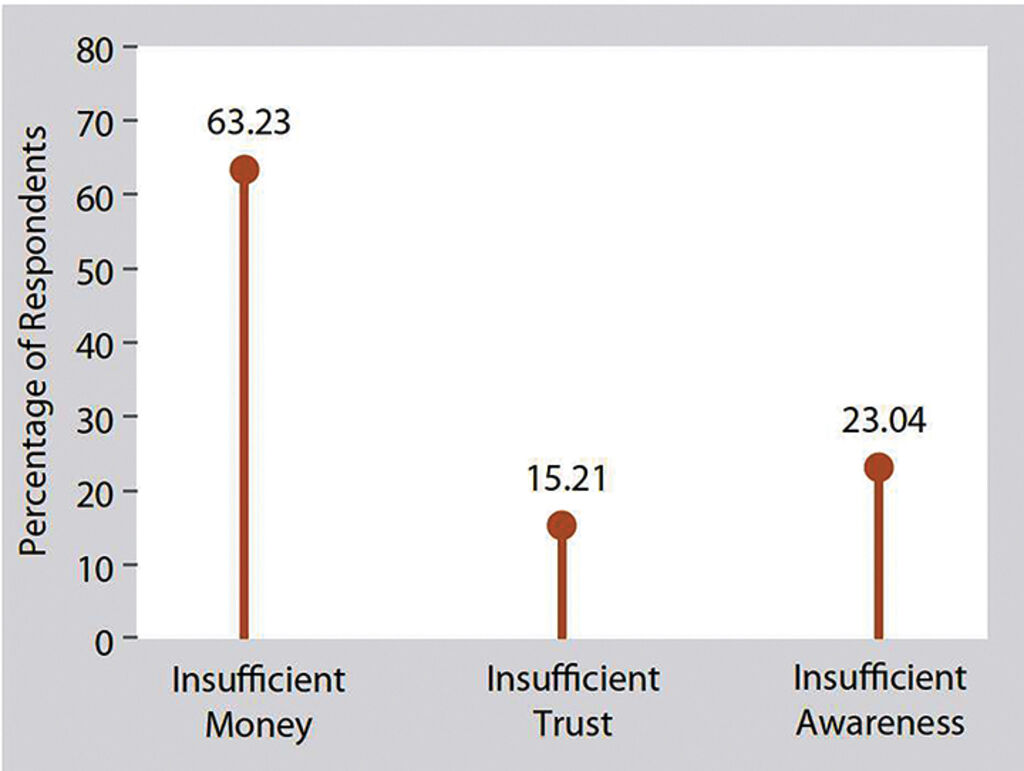

As Figure 5 shows, social insurance is one of the most prevalent forms of savings for the future among more than a quarter (29.43 percent) of the 2024 PAPI respondents. This means that a large segment of the population[6] remains exposed by this lack of a safety net. To discover why, PAPI in 2024 probed respondents’ rationale for not enrolling in voluntary social insurance. Figure 10 shows that financial constraints left the majority (63.23 percent) shut out of insurance coverage. Revealingly, 15.21 percent said they did not trust that the money would be paid out upon retirement. This is a critical finding. Lack of transparency about how money in social insurance accounts is protected and invested is a critical deterrent to its use and a major driver of early withdrawals. In addition, over one-in-five (23.04 percent) of respondents said they did not have insurance because they had insufficient awareness of the scheme and how it worked.

|

| Figure 10: Reasons for not having voluntary social insurance, 2024 |

The 2024 Law on Social Insurance aims to remedy these roadblocks to citizens acquiring social insurance. On the financial side, it will increase benefits without increasing the cost. The Government has also launched an awareness campaign to publicize the benefits of the revised voluntary insurance scheme. If all these commitments are realized, they may over time reduce citizens’ perceptions of economic precarity. Future PAPI reports will assess the degree to which the new law successfully incentivizes citizens to acquire social insurance.

Conclusions

This article reveals a complex picture of social insurance coverage and savings among Vietnamese citizens. While social insurance coverage has broadened since 2019, its distribution remains uneven across sectors, with limited access for informal workers, migrants and ethnic minorities, and the lack of transparency about how social insurance contributors’ money is protected and invested. The 2024 PAPI survey also highlights a concerning lack of savings for retirement among a significant portion of the population, contributing to economic insecurity and heightened poverty concerns. The recently enacted Law on Social Insurance, effective from July, aims to address these challenges by enhancing benefits and launching awareness campaigns to encourage voluntary enrolment. However, the degree to which they gain traction remains to be seen.

Based on the findings, several solutions are offered. As the 2024 Law on Social Insurance is now in effect, it is crucial to ensure simplified and transparent application procedures for social insurance schemes, especially voluntary ones, and to widely communicate the benefits of social insurance enrolment. Social insurance coverage can be enhanced when trust in the social insurance fund is built and social insurance targets those working in informal sectors, migrant workers and ethnic minority employees through tailored schemes and accessible registration platforms. More importantly, financial literacy programs and diverse savings mechanisms for citizens in need are crucial to ensure no one is left behind.

Finally, making insurance accessible and affordable for marginalized populations is critical to citizens’ economic prosperity. Migrant workers and ethnic minority groups are less likely to access social insurance. These groups, as well as men, are also more likely to withdraw their contributions early. Such economic precarity can negatively impact their economic perceptions. This suggests that improving access – the goal of the 2024 Law on Social Insurance– will be key to reducing concerns about poverty and economic dissatisfaction. To achieve this, it is essential to make social insurance schemes more accessible and affordable for the marginalized population groups.-

[1] For further information about PAPI, visit www.papi.org.vn/eng.

[2] See the 2024 PAPI Report at https://papi.org.vn/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/PAPI_2024_REPORT_ENG_final.pdf.

[3] To understand the reality of access to social insurance in Vietnam, it is important to distinguish between two forms of social insurance: compulsory and voluntary. See Vietnam Social Security at https://baohiemxahoi.gov.vn/nhungdieucanbiet/pages/bao-hiem-xa-hoi.aspx and the Government Newspaper (August 13, 2024), 14 new and important provisions of the 2024 Law on Social Insurance, available at https://xaydungchinhsach.chinhphu.vn/14-noi-dung-moi-trong-tam-cua-luat-bao-hiem-xa-hoi-2024-119240806172349712.htm for more details.

[4] The Van Thinh Phat case, one of Vietnam’s largest financial fraud trials, centers on Truong My Lan, Chairwoman of Van Thinh Phat Group. She was convicted of siphoning billions of dollars from Saigon Commercial Bank (SCB) through fraudulent loans and bond issuances, manipulating the bank and violating lending regulations. The scale of the fraud, involving shell companies and bribery, shocked the nation. The case highlighted vulnerabilities in Vietnam’s financial system and raised concerns about corruption and oversight. The widely covered trials had significant repercussions for the real estate and banking sectors.

[5] See Vietnam Social Security (September 9, 2023). Early exit from social insurance scheme: causes and remedies. Available at: https://vss.gov.vn/UserControls/Publishing/News/BinhLuan/pFormPrint.aspx?UrlListProcess=/content/english/tintuc/Lists/EnNews&ItemID=11734&IsTA=True.

[6] PAPI surveys citizens within an age range of 18-75 years.