Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development and the United Nations Development Program

Introduction

The 2013 Constitution and other laws recognize privacy as a fundamental right in Vietnam. As digital transformation of the public sector is accelerated, a large amount of data on personal information is collected via such tools as electronic provincial government portals (e-government portals - EGPs), online public service portals (e-service portals - ESPs), and smart applications (apps) put into use by provincial-level People’s Committees. However, protecting personal data and ensuring user privacy on those interfaces have not received adequate attention. There are still gaps in the policies of those platforms to meet the current legal provisions, especially in comparison with good practices.

Within this context, based on the current legal framework, the Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development (IPS) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has recently conducted a review to evaluate the personal data and privacy protection practices on EGPs and ESPs of all 63 provinces as well as apps being put into use by 50 provinces.[1] Two dimensions were assessed: (i) privacy policies issued by local governments; and, (ii) specific measures to implement such policies through technical tools.

This article presents key findings from the review. It also provides policy and practical recommendations for central and local government agencies on how to improve personal data and privacy protection on online government-citizen interaction interfaces at the provincial level in Vietnam.

|

Thematic discussion on personal data protection on local governments’ websites in Hanoi, June 28, 2022__Photo: Van Anh, UNDP Vietnam |

| Thematic discussion on personal data protection on local governments’ websites in Hanoi, June 28, 2022__Photo: Van Anh, UNDP Vietnam |

Key review findings

Considering the rising threat and cost of data breach from the public sector and the increasing collection of citizens’ sensitive data from digital government activities, it is necessary to assess and monitor personal data processing practices of government agencies. The review, which was conducted from March to May in 2022, sought to improve personal data protection awareness of local governments in Vietnam’s digital environment by reviewing privacy policies and technical measures on three types of government-citizen interaction interfaces, including EGPs, ESPs, and apps across all 63 provinces. The review was conducted based on 17 specific indicators[2], which include, inter alia, whether privacy policies specify government agencies responsible for protecting privacy; types of information collected by local governments; with which third-party agencies the personal information is shared; and children’s privacy regulations. Below are key findings from the review.

Data security and personal data privacy violations: inevitable risks to manage

In Vietnam, digitalization of information and the public sector’s e-services have resulted in collection and concentration of citizens’ sensitive data in the digital space. The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) completed the national population database in 2021 and is aiming to have 100 percent of personal identification accounts established on ESPs at national, ministerial, and provincial levels digitally authenticated in 2022. The Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) has built the National Data Exchange Platform, which connects with more than 90 ministries, sectors, provinces, and enterprises, with 10 databases and eight information systems. In 2021, the Platform has facilitated 180,919,031 data transactions[3] (about 500,000 transactions per day), which helped increase data reuse and reduce duplications of data registration.[4]

As a result, data security and personal data privacy violations have become inevitable risks that need to be managed. This tendency became self-evident during the first phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the mainstream media and the authorities often revealed COVID-19 carriers’ private information, including names, addresses, medical data, and private affairs. According to the MPS’s statistics, there were 2,500 fraud cases taking place in the digital space between May 2020 and May 2021. Of these, there were 527 cases involving criminals faking to be government officials and deploying scams for financial frauds. While there is not yet proven causal link between fraud cases and data breach, it appears that identity theft, which involves either counterfeiting or misusing personal data, is on the rise. With 50 million chip-based identity cards to be issued to citizens by July 1, 2022, and the national population database subsequently becoming the backbone enabling digital transactions, identity theft could result in even more grave impacts.

There is other evidence that Vietnam’s public sector appears to perform poorly in data protection. The Vietnam Digital Transformation Index (DTI) in 2021[5] suggests that enhancing information security be one of the two priorities to improve digital government performance at both ministerial and provincial levels. Compared to other indicators such as digital transformation awareness, digital governance and digital infrastructure, information security in the 2021 DTI received low ratings of 0.2948 across ministries and 0.3267 across provinces on the 0-1-point scale.

Local governments’ limited awareness and practice of personal data and privacy protection on online government-citizen interaction interfaces

The review shows that 59 in 63 EGPs and 60 in 63 ESPs have not yet published a Privacy Policy - a form of an e-agreement that establishes responsibilities of state agencies to protect citizens’ data and provides a legal basis for citizens to exercise their rights to personal data in events of data breach or personal data violation. Policies and tools related to personal data and privacy protection on EGPs, ESPs, and apps of provinces deem spontaneous and have not stemmed from explicit awareness of the importance of privacy.

Although the documents on information security issued by the local governments can be easily accessed online, they mention technical requirements to ensure the safety and security of data, prevention of cyber risks, and cyber security rather than personal data privacy and users’ privacy. In fact, provincial-level state agencies have not paid adequate attention to personal data protection in real terms. There were no specific terms and conditions on personal data protection on 59 EGPs and 60 ESPs. As the review shows, none of the 63 provinces have set a good practice in all respects regarding personal data protection. Most provincial interfaces only require users to confirm that the information they provide is accurate but do not supply tools for users to express their privacy preferences.

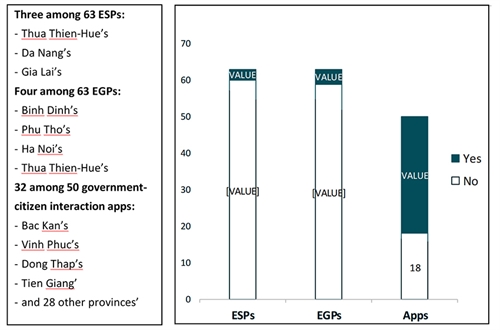

Considering the privacy protection in the entire process of local government interaction with citizens in the digital environment, the input factors such as information technology facilities and infrastructure have been provided with more attention, as the finding from the 2021 DTI[6] shows. However, the implementation of personal data and privacy protection policies and laws requires further improvements. In particular, the outputs, including the degree to which personal data are protected, have not met the requirements of the existing legal framework. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, privacy policies have not been given due attention, reflected in both the quantity and quality of privacy policies.

|

|

| Privacy policies on apps | Privacy policies on EGPs[7] | Privacy policies on ESPs |

| One (Hau Giang) out of 32 provinces with apps with privacy policies identifies the Provincial People’s Committee as the agency responsible for data control. Five (Binh Dinh, Da Nang, Dong Thap, Thua Thien-Hue, and Vinh Long) among 32 provinces with apps have issued privacy policies establishing agreements between provincial Departments of Information and Communications (DICs) and users. Eleven (Bac Kan, Bac Lieu, Ben Tre, Can Tho, Hoa Binh, Hung Yen, Kon Tum, Long An, Quang Nam, Quang Ninh, and Soc Trang) among 32 provinces with apps have issued privacy policies establishing e-agreements between service providers and users. Fifteen out of 32 provinces (An Giang, Ba Ria-Vung Tau, Cao Bang, Hai Phong, Kien Giang, Lai Chau, Lang Son, Ninh Binh, Phu Yen, Son La, Tay Ninh, Thai Binh, Thai Nguyen, Tien Giang, and Vinh Phuc) did not clarify which agency is responsible for protecting the privacy of data subjects, just stated very generically as “We”. | Four provinces that have announced privacy policies on EGPs (Binh Dinh, Phu Tho, Ha Noi and Thua Thien-Hue) do not accurately identify the agency responsible for data collection and control. | One (Da Nang) out of three privacy policies published on ESPs established an agreement between the DICs and users[8]. One (Gia Lai) out of three privacy policies published on ESPs established an e-agreement between the service provider (WSO2 Identity Server) and users.[9] One (Thua Thien-Hue) out of three privacy policies published on ESPs do not clarify which agency is responsible for protecting the privacy of data subjects. |

In particular, in terms of quantity, a total of 39 privacy policy documents were found across all three online interfaces of local governments in 63 provinces. Among these, only three ESPs of Da Nang, Gia Lai, and Thua Thien-Hue and four EGPs of Binh Dinh, Phu Tho, Ha Noi, and Thua Thien-Hue have published privacy policies.

Of the 50 provinces whose apps are searchable on Google Play and Apple Store, 32 apps have included and publicized privacy policies, whilst the remaining 18 have no privacy policy or their privacy policy is inaccessible. The higher rate of privacy policy publication on apps compared to EGPs and ESPs can be attributable to the built-in technical requirements of Google Play and Apple Store, which make it mandatory for app developers to publish privacy policies upon apps’ launch.

In terms of quality, none of the identified privacy policies fully satisfy the conditions set forth in the 2006 Law on Information Technology, Government Decree 64/2007/ND-CP and MIC’s Circular 25/2010/TT-BTTTT, as well as the six United Nations principles on personal data protection and privacy. Most of the existing privacy policies fail to establish effective e-contracts between the responsible government agencies (People’s Committees of local governments) and data subjects (users of EGPs, ESPs, and apps). Unclear attribution of the right to data control leads to common confusion about their legal responsibilities of the government agencies (People’s Committees of local governments), the operating agencies (DICs), and the service providers (private companies/individuals).

For privacy policies to establish a legal relationship between data subjects and the responsible government agencies, misidentification of the responsible agencies will lead to failure in safeguarding data subjects’ rights by holding the responsible agencies accountable to their legal responsibilities, including to provide access, correct or delete data when requested, address administrative and judicial appeals, and communicate personal data breaches to data subjects. Out of 39 provincial privacy policies reviewed, only one from the app of Hau Giang province correctly identifies the provincial People’s Committee as the agency responsible for determining the purpose and the meaning of data processing, and the DIC as the operating agency, which processes personal data on behalf of the People’s Committee.

Another poor practice is found in the contact mechanism, which is important for establishing digital contracts between local government agencies and data subjects. Yet, only eight of the 39 privacy policies provide official government emails, while 13 provide personal/business emails. The privacy policies of the apps of Can Tho and Quang Nam even shared the same contact email address[10], which indicates that they have copied the policy from one another without an effort to localize the email contact.

Gaps in the policy framework and general legislation on personal data protection

Inadequacies in the practices of personal data and privacy protection on the online government-citizen interaction interfaces, as found from the review, indicate a number of gaps in the existing policy and legal framework on personal data protection.

First, Vietnam has not clearly defined and classified personal data in accordance with the new trends of digital transformation, including the types of personal data collected from users on the interaction interfaces of the authorities. The 2018 Law on Cyber Security[11] provides an overly broad (thus unclear) definition of personal information, while the definition offered in Government Decree 64/2007/ND-CP is too narrow. Only the MIC’s Circular 25/2010/TT-BTTTT mentions personal information collected automatically on government agencies’ e-portals.

Second, data privacy and privacy right are not yet clearly defined. As the existing legal framework was built before personal data privacy protection becomes a social contention, it focuses more on technical requirements to ensure data security rather than data privacy. As a result, the local governments currently appear to focus more on data security (government agencies versus external cyber threats) rather than data privacy (government agencies versus data subjects) aspect.

Third, the policy and legal framework have not clearly distinguished between the data controller and the data processor. Therefore, it is challenging to clearly define the liabilities of such entities toward data subjects. For example, when a state agency publishes a privacy policy document, can it be considered a basis for determining its liability regime? Or when a data breach occurs, whose responsibility is it to notify users and compensate for data subjects? In addition, the legal relationship between state agencies collecting personal data and service providers offering those online interfaces is not clear.

Fourth, it is unclear how privacy protection is integrated into processes and procedures of storing, using and sharing large volumes of personal data collected by state agencies. The most typical gap is in the detention time.

Fifth, the law does not yet contain regulations on personnel acting as focal points for personal data and privacy protection in the operation of state agencies. This is let alone specifications about the focal points’ tasks or requirement to publicize their contact information as part of the requirement in digital contract terms and conditions between state agencies and users of e-services or e-government portals.

Sixth, mechanisms for handling violations, settling complaints, lawsuits, compensation for damage, and sanctions related to personal data and privacy protection in the public sector in the digital environment have not been clearly and specifically regulated. This fails to match the fast-changing digital transformation trends and requirements for e-government evolution.

Seventh, there is a lack of specific regulations and guidelines for provinces to comply with to better protect personal data and privacy of citizens in the digital environment. This has contributed to the inconsistency across provinces in their practice of protecting personal data and privacy on local governments’ online interfaces with citizens.

Conclusions and recommendations

While the Government of Vietnam has been working on combating illegal commercialization of personal data in the private sector, little attention has been paid to ensure that government agencies at all levels practice the protection of personal data privacy on Internet-based interfaces. It is important that the central and local governments in Vietnam take personal data protection in the public sector seriously. As digital identities, which are created, authenticated and managed by the Government, become the backbone of digital economy activities, and personal data protection is integrated into all new-generation digital trade agreements and digital economy partnership agreements, guaranteeing protection of personal data and winning public trust in digital transformation will not only serve digital governance purposes, but also contribute to sustainable development of Vietnam’s digital economy in the long run. Below are important recommendations upon the review findings.

Enhancing the national regulatory framework on personal data and privacy protection on government-citizen interaction interfaces

At the national level, the following six suggestions related to the protection of personal data and privacy need to be considered when Vietnam reviews or develops legal documents that govern government interfaces like ESPs, EGPs or other types of government-citizen interaction interfaces:

- It is required to explicitly define and classify personal data in line with the latest digital transformation trends, including types of personal data collected from users on government interfaces. At the same time, it is vital to distinguish between data privacy and data security, because data privacy is concerned with protecting personal privacy while data security focuses on protecting the information technology system and security of state agencies.

- It is necessary to distinguish between data controllers and data processors, thereby explicitly defining the legal responsibilities of those parties toward data subjects. The regulatory framework must establish the default liability of state agencies when publishing privacy policy documents, by specifying, for instance, tools for individuals to exercise their rights to agree or disagree with the provision of personal information on government applications or interfaces.

- Provisions related to the handling of violations during the processing of personal data by state agencies, officials, and civil servants should be refined. Types of violations and appropriate sanctioning measures should be specified. For instance, there should be requirements for state compensation for government agencies’ breaches of personal data protection; administrative, criminal and civil processes and procedures for handling violations of personal data and privacy; and a focal agency to receive and process requests and complaints related to personal data.

- Relevant laws should contain provisions on assigning personnel in charge of personal data and privacy protection in related state agencies, at least at the provincial level. The profile and contact information of such a person should be published for citizens to liaise with when needed. This person is responsible for providing advice to local government agencies on personal data and privacy protection; monitoring local governments’ compliance with legal regulations, common standards, and internal rules on privacy and personal data protection; and, serving as a contact point between data subjects and governing bodies when necessary.

- To achieve consistency across all provinces in personal data and privacy protection practices, the MIC should develop sample privacy documents for local government agencies to apply when providing online public services to ensure standardized personal data and privacy protection. These shall include, inter alia, a sample privacy policy and sample terms of use between the responsible government agencies and users, and a sample contract between the government agencies and service providers of government-to-citizen interaction interfaces.

Good privacy practices at the provincial level from the review show that local governments should consider three important actions: developing local action plans suitable for local contexts, focusing on the implementation process, and meeting the rights and interests of citizens. Personal data and privacy protection policies, as well as practical tools to implement those policies on interaction interfaces, need to closely follow and meet all requirements in relevant Vietnamese laws and regulations. In particular, there should be clear identification of major responsible agencies, tools, and channels to receive comments or complaints about personal data and privacy violations, and public feedback on the quality and effectiveness of privacy protection.

Protecting the rights and interests of citizens using services, products, and tools on EGPs, ESPs, and apps is a must for local governments. Therefore, local governments’ performance in this aspect should be conducted regularly to ensure that personal data and privacy are better protected. Also, there should be specific measures and tools to assist local governments in ensuring the legitimacy and lawfulness of processing personal information, collecting and using personal information for specific purposes, collecting personal information limited to stated purposes, and specifying information storage duration as well as in increasing the transparency and accountability in the collection, processing, storage, and use of personal information.

Evaluating personal data and privacy protection performance by state agencies on digital interfaces

It is recommended that the review of government performance in the protection of personal data and privacy be expanded to all levels of governments, not only local governments. Indicators and targets on personal data and privacy protection should be added to the national digital transformation goals and criteria for evaluating personal data protection to Vietnam’s DTI.

Also, in-depth reviews of personal data and privacy protection practices by state agencies at all levels should be regularly carried out. The review should not only be limited to EGPs, ESPs, and apps, but also to databases managed by state agencies, where personal data are stored, used, and shared after being collected from interaction interfaces.-