Introduction

Access to local land use plans remains limited on a national scale despite the provisions of the 2013 Land Law and the 2016 Law on Access to Information which mandate the posting of local land use master plans and annual land use plans for public view in various forms, including on digital platforms. According to the 2021 Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) survey, only one-fifth of respondents nationwide said they were aware of local land use plans since 2011.

Findings related to land governance[1] from annual PAPI surveys[2] and the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI)[3] suggest that the lack of transparency in land planning and acquisition schemes, low land compensation frameworks, and rent-seeking behaviors among land registrars may have been the main causes of land conflicts in Vietnam, especially in suburban areas.

Therefore, it is necessary to enhance disclosure of information on district land use plans and provincial land price frameworks in order to mitigate land conflicts and promote good land governance in Vietnam. The fair and transparent disclosure of such information and the ability of citizens to comment on draft land use plans and price frameworks would increase citizens’ trust in local governments and likely decrease the risks of corruption and the prevalence of land conflicts.

This article presents key findings from an empirical research initiative called “Action Research to Enhance Citizens’ Access to Land Information”[4] conducted by the Center for Education Promotion and Empowerment of Women (CEPEW) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Vietnam, with technical support from Real-Time Analytics, since July 2021. The initiative has sought to improve land governance by reviewing public access to information on land use plans and price frameworks by the district governments in all 63 provinces, making such information available on a land transparency portal, and experimenting on requests for land information as provided by provincial and district governments.

Significant awareness gaps of local land use plans among citizens

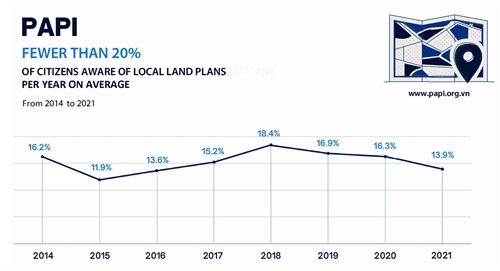

Results from the 2021 PAPI survey demonstrate that a majority of Vietnamese do not know the local land use plan of their district. Figure 1 shows how less than one-fifth of the population has been aware of local land use plans from 2014 to 2021, with a steady decrease from 18.4 percent in 2018 to 13.9 percent in 2021.

|

Another concerning statistic from the survey is that over half of respondents do not know how to gather information on local land price frameworks. When asked if they would know where to look for the information on the official land price frameworks issued by the local governments (including consultations with local People’s Committees, non-state real estate experts, and searches on government websites, etc.), only 42.4 percent of respondents said “yes.” Moreover, only 13.9 percent of respondents reported having an opportunity to provide comments on local land use master plans and plans in 2021.

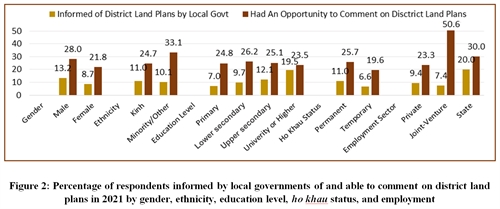

Further analysis of the 2021 PAPI survey results illustrates imbalances in respondents being informed by their local governments of district land use plans, as well as in their ability to provide comments on these plans based on certain demographic characteristics. For example, a gender gap exists in being informed of land plans by local officials in favor of males (13.2 percent) over females (8.7 percent), as seen in Figure 2. This gender divide also slightly increases in being able to provide a comment on the local land use plans, with males being 6.2 percent more likely than females to do so.

|

There is relatively no information gap along ethnic lines with respondents of Kinh and other minority ethnicities being nearly equal in being informed by local governments of district land use plans (11 percent and 10.1 percent, respectively.) However, ethnic minorities (33.1 percent) are 8.4 percent more likely than Kinh people (24.7 percent) to have had an opportunity to comment on district land plans.

Education appears to have a positive correlation with land use plan awareness. Respondents who possess a university or higher (postgraduate) education are 7.4 percent, 9.8 percent, and 12.5 percent more likely to be informed by local governments of district land use plans than those with upper secondary, lower secondary and primary education, respectively. Despite the benefit associated with one’s level of education in this aspect, respondents with a university or higher education (23.5 percent) were more or less equal to those with upper secondary (25.1 percent), lower secondary (26.2 percent), and primary education (24.8 percent) in the likelihood of being able to comment on their districts’ land use plans.

A person’s ho khau or permanent household registration status also influences his probability of being informed by local authorities and having an opportunity to comment on district land use plans. Respondents who have their ho khau within the commune where they currently reside, known as permanent residents, were 4.4 percent more likely to have been informed of district land use plans by local officials than temporary residents, or those lacking a ho khau in their commune of residence. This gap increases in terms of being able to provide a comment on the land use plans with permanent residents (25.7 percent) being 6.1 percent more likely than temporary residents to do so.

However, the largest gaps in people’s ability to be informed of and comment on district land use plans appear to be based on the economic sector in which they are employed (state, joint-venture, or private). Figure 2 also shows how state employees (20 percent) were over two times more likely than private-sector employees (9.4 percent) and joint-venture employees (7.4 percent) to have been informed by local officials of district land use plans. More striking is that just over half of joint-venture employees (50.6 percent) reported having an opportunity to comment on district land use plans. This is so significantly more than the nearly three-in-ten (30 percent) state employees and one-in-four (23.3 percent) private-sector employees.

Key findings from the action research

Regulations on disclosure and provision of land information at the request of citizens

The disclosure and provision of information on provincial land price frameworks and district land use plans at the request of citizens are stipulated in the 2013 Land Law and the 2016 Law on Access to Information as well as in a number of related documents such as Government Decree 148/2020/ND-CP and Decree 13/2018/ND-CP, Circular 29/2014/TT-BTNMT of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, and Circular 46/2018/TT-BTC of the Ministry of Finance (Table 1).

| No. | Type of informa-tion | Formulating and disclosing agency | Issuing or approving agency | Disclosure regulation | Online disclosure | Date of posting | Duration of posting | Applicable period | Research period |

| 1 | District land use plans | District People’s Committee | District People’s Committee | Must be disclosed | Yes | Within 15 days after issuance by December 31 | Throughout the planning period | Every year | 2021 |

| 2 | Provincial land price list | Provincial People’s Committee | Provincial People’s Committee | Must be disclosed | Not specified | January 1 of the first year | Not specified | Every five years | 2020-24 |

By the above regulations, the provision of information and data about land, information about land markets, and other land information is one of the service activities in the field of land. The land price framework is formulated by the provincial-level People’s Committee and submitted to the same-level People’s Council for review before promulgation. The land price framework is developed once every five years and publicized on January 1 of the first year of the period. During the implementation of the land price framework, if the Government adjusts the land price framework or the common land price in the market fluctuates, the provincial People’s Committee shall adjust the land price framework accordingly. However, as the review shows, there is a lack of regulations on the form and channels for publicizing the provincial land price framework.

Meanwhile, district land use plans are formulated annually. Based on the complete dossier of the district-level annual land-use plan and the resolution of the provincial People’s Council, the provincial Department of Natural Resources and Environment submits it to the provincial People’s Committee for approval before December 31. The district land use plan must be publicized after being approved by a competent state agency. District-level People’s Committees shall publicize district land use master plans and plans at their head offices and on their portals and publicize the contents of the district land use master plans and plans related to communes, wards, and townships at the head offices of the commune-level People’s Committees. The disclosure shall be made within 15 days from the date of approval by competent state agencies.

Results of the review of portals or websites of local state agencies

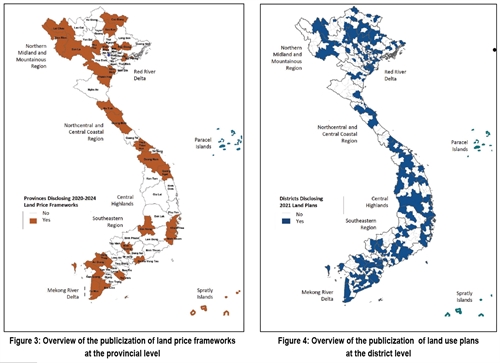

Upon the four-step process to search for information on the portals/websites of the People’s Committees of 63 provinces and 704 districts nationwide, the results (Table 2) showed that only 27 out of 63 provinces have publicized provincial land price frameworks and only 337 out of 704 district-level agencies have publicized district land use plans on their portals or websites.

| No. | Type of information | No. of disclosure | Disclosure rate (%) | Timely disclosure | ||

| Yes | No | Unknown | ||||

| 1 | District land use plan in 2021 | 337/704 | 47.9 | 123/337 | 135/337 | 79/337 |

| 2 | Provincial land price framework in 2020-24 | 27/63 | 42.9 | 2/27 | 14/27 | 11/27 |

Figure 3 gives an overview of the disclosure of the provincial land price frameworks during the 2020-24 period in 63 provinces/municipalities, while Figure 4 highlights the districts where the information on land use plans in 2021 has been publicized on their portals or websites.

|

However, there is a lack of consistency in the posting of information by state agencies, especially with district land use plans, as the to-be-disclosed documents listed in the announcement of publicization are often scattered in different categories on these portals or websites, which makes it difficult for citizens to find information in full.

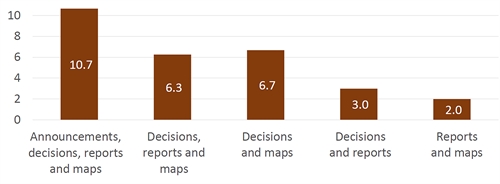

Figure 5 shows that the level of completeness in the disclosure of the required documents in land use plans by district-level People’s Committees (agencies) varies among districts/towns/cities in provinces/municipalities nationwide. Overall, only 17 percent of agencies published a complete set of land use plan documents which includes four types of documents: (i) announcement of publicization of land use plans, (ii) decision on the approval of district land use plans, (iii) explanatory report, and (iv) map of land use plans; or published the most three important documents except the announcement of publicization of land use plans. Specifically, 75 agencies (accounting for 10.7 percent) publicized all four types of documents; 44 agencies (6.3 percent) publicized decisions on approval of land use plans, explanatory reports, and maps of land use plans; 47 agencies (6.7 percent) publicized decisions on approval of land use plans and maps of land use plans; 21 agencies (3 percent) posted decisions on approval of land use plans and explanatory reports; and 14 agencies (2 percent) posted explanatory reports and maps of land use plans. Among the agencies that have publicized the above two types of information, many agencies publish them in ZIP files, which makes it difficult for information users to access.

|

Results of requests for land information

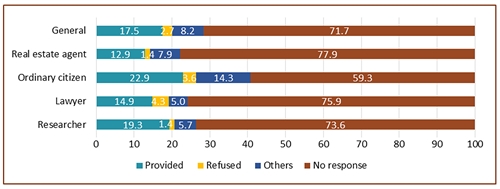

Based on random sampling, members of the Research Team sent out requests for information on district land use plans to the offices of 561 out of 704 district-level People’s Committees nationwide with five members assuming four different roles, including an ordinary citizen, a real estate agent, a lawyer, and a researcher. On average, 140-141 request letters corresponding to each role were sent by the Research Team members, of which 70 letters cited the 2016 Law on Access to Information and the other 70 letters did not cite any legal provisions.

Figure 6 shows the results of requests for information on district land use plans. Of the 561 offices of district-level People’s Committees to which requests for information were sent, 98 agencies (accounting for 17.5 percent) provided the requested information, 15 agencies (2.7 percent) refused to provide the requested information, and 46 agencies (8.2 percent) responded but did not provide the requested information. There was an overwhelming number of 402 agencies that made no response (accounting for 71.7 percent). Regarding the four roles of the Research Team members, the rate of response is highest for ordinary citizens (22.9 percent of the 140 requests submitted), followed by researchers (19.3 percent), lawyers (14.9 percent), and real estate agents (12.9 percent).

|

The 2016 Law on Access to Information stipulates that state agencies are responsible for providing information created by themselves, except commune-level People’s Committees, which are responsible for providing citizens residing in their localities with information created by themselves and by agencies at the same level and information received by themselves to directly perform their functions, duties, and powers; and provide other citizens with such information in cases that directly relate to their lawful rights and interests. This provision may be a barrier to the provision of information by the office of the district-level People’s Committee regarding the information requested by the Research Team members.

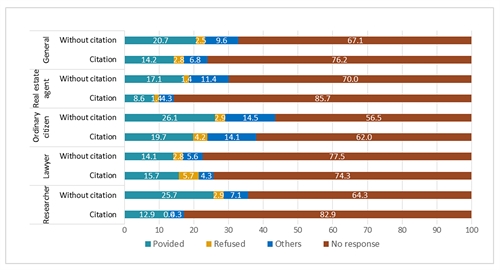

Figure 7 shows the differences in the response rate regarding groups of requests with and without citation of legal provisions. Overall, the rate of information provision for requests with citation was higher (20.7 percent) than that of requests without citation (14.2 percent). The same goes for the rate of responding but not providing information, which was 9.6 percent for requests with citation compared to 6.8 percent for requests without citation. The rate of refusal of information provision for requests without citation was 2.8 percent and for requests with citation was 2.5 percent. The rate of unresponsiveness to requests with citation was lower (67.1 percent) than that of requests without citation (76.2 percent).

|

The communication between the Research Team members and the civil servants assigned to respond to citizens’ requests for information showed that most civil servants had a polite attitude during the interaction. However, there seems to be confusion or ambiguity about the agencies with the responsibility to provide information, even though land information is at least held by the Office of the district-level People’s Committee and the provincial-level Department of Natural Resources and Environment. Regarding means of communication, many civil servants preferred communicating with citizens via Zalo. One even advised the requester to directly contact him/her through Zalo in case he/she needs any help and there is no need for a complicated letter (request for information form).

Regarding the content of the information provided, most agencies responded by providing only decisions on the approval of land use plans without other documents.

Recommendations

To ensure the effective implementation of citizens’ right to land information and to contribute to the promotion of good land governance and mitigation of land conflicts, below are key recommendations regarding policy amendment, promulgation and implementation.

Laws and policies relating to the disclosure of land information should be amended and promulgated so that the process of providing information at the request of citizens is integrated into the current set of administrative procedures as all state agencies are entities that create and hold information. The 2016 Law on Access to Information has clearly defined the responsibilities, procedures, and deadlines for information disclosure and information provision at the request of citizens. It is also recommended that policymakers supplement specific regulations on forms and channels for publicizing provincial land price frameworks in relevant legal documents.

To enforce existing laws and policies more effectively, People’s Committees at all levels should organize training courses on the 2016 Law on Access to Information. During these training courses, nine tasks each state agency needs to perform as specified in the 2016 Law on Access to Information and Government Decree 13/2018/ND-CP should be highlighted. In addition, they should open training classes on regulations and procedures related to disclosure of land information and provision of information at the request of citizens.

Moreover, People’s Committees at all levels should implement more effectively the 2016 Law on Access to Information, thereby contributing to better implementation of land information disclosure in accordance with the 2013 Land Law. Accordingly, state agencies need to quickly perform the following tasks: (i) issue and publicize internal regulations on providing information within the scope of their responsibilities; (ii) assign and publicize the information of the focal point for information provision; and (iii) set up a section on access to information on the agency’s portal/website and create a list of information to be disclosed, including information on land use master plans, land use plans and land price frameworks.

State agencies should publicize land information in the direction of fully posting documents related to a set of land use master plans, land use plans, or land price frameworks into a specific category according to the 2016 Law on Access to Information. For example, for a set of land use plan dossiers, it is necessary to publish the announcement of publicization of the land use plan, the decision on the approval of the district land use plan, the explanatory report, and the map of the land use plan.

Additionally, state agencies should, as required by Circular 26/2020/TT-BTTTT of the Ministry of Information and Communications, publicize information in a way that ensures accessibility and usability to people with disabilities, the elderly, and other people other than posting the information in ZIP files as in current practice.

Finally, the search function on portals or websites of state agencies should be improved while specific instructions on document publicization should be provided for state agencies at the district level to improve their implementation.-