|

| Inside a workshop of Nghia Nipper Corporation, a leading enterprise in manufacturing and trading in nail care tools in Vietnam__Photo: Hong Dat/VNA |

Center for Community Support and Development Studies, Vietnam Fatherland Front Center for Research and Training, and United Nations Development Program

Introduction

As Vietnam entered 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic spiked but gradually eased after April, allowing the country to resume socio-economic activities. As a result, Vietnam’s 2022 economic picture consisted of both bright and dark spots. The economic growth rate hit 8.02 percent by the year’s end, in sharp contrast to the 2021’s 2.56 percent.[1] However, high domestic inflation and negative market sentiments at times impacted public confidence. For instance, the country’s 2022 inflation rate was at 3.15 percent, yet it spiked to 4.55 percent in the last quarter due to hikes in prices of gasoline, oil and food. In October and November 2022, Vietnam had one of the world’s worst-performing stock markets.

These macro indicators are important as they also affect Vietnamese citizens’ satisfaction with and confidence in government. They are of greater significance for internal migrants that move to other provinces for jobs, livelihoods or other purposes. In fact, as internal migration has increased over time in Vietnam, the share of non-permanent residents residing in many provinces has increased. These migrants have their own demands for governance and service delivery, while their presence affects how pre-existing permanent residents experience and perceive those services. At the same time, sending provinces have lost large shares of their younger populations to receiving provinces, causing a gap in understanding how younger populations would expect from their home provincial governments.

This article[2] presents key insights into internal migration, and how local governance can be made more inclusive for migrants, along with identifying migrants’ issues of greatest concern as well as the driving forces behind internal migration for policy consideration in 2022. It is an excerpt from the 2022 Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) Report, which was launched on April 12, 2023.[3] Since 2021, migrants have become part of the population sampled and surveyed in PAPI, building on the insightful 2021 survey of temporary residents in 12 provinces with positive net in-migrant rates (including Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, Binh Duong, Dong Nai, Bac Ninh, Can Tho, Long An, Ba Ria-Vung Tau, Dak Nong, Thai Nguyen and Lai Chau) based on the 2019 Census.[4] In 2022 in particular, of the total survey sample of 16,117 respondents from across Vietnam, 14,931 were permanent residents from 63 provinces nationwide, and 1,186 were temporary residents from 12 provinces.

Migration impacts on local governance

This section presents findings on migrants’ perceptions of and experiences with local governance and public services in 2022, with some comparative perspectives with the findings in 2021 when surveys on internal migrants were officialized in annual PAPI surveys. The 2022 PAPI survey repeated the previous years’ questionnaire modules, which ask long- and short-term migrants about their experiences in receiving provinces. The findings help provide important insights into how internal migrants are treated in their host provinces in terms of access to public governance performance and public service delivery and ask local governments of receiving provinces to address gaps and differences to be more inclusive of migrants in everyday governance matters.

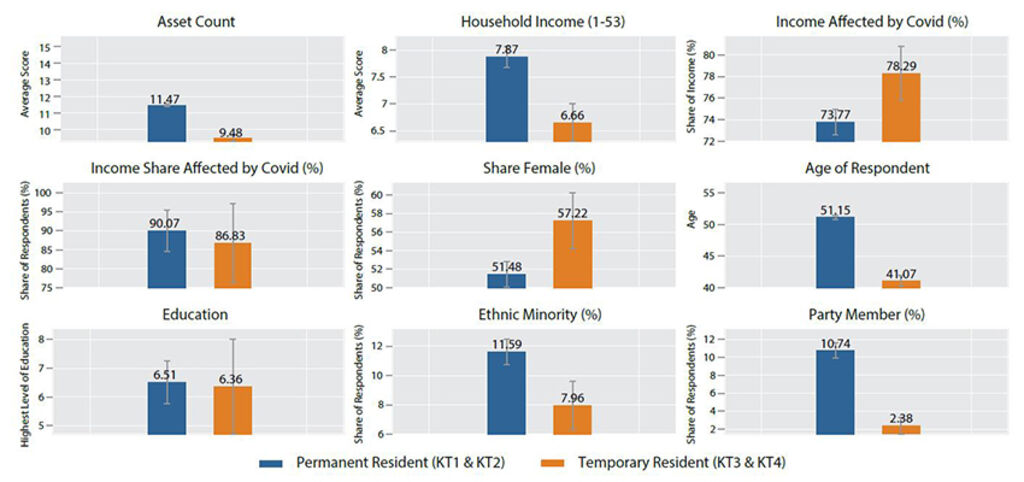

Findings from the 2022 survey show that, there are clear differences between the demographics of migrants and permanent residents, similar to findings in 2021.[5] As Figure 1 reveals, migrants tend to be poorer with fewer household assets and marginally less income than residents. They are younger on average, less educated and more likely to be women. Most dramatically, they are significantly less connected to people of political influence as only 2.4 percent are likely to be Party members, compared to 10.7 percent in the permanent resident sample.

|

| Figure 1: Differences in demographic characteristics of migrants vs. permanent residents, 2022 |

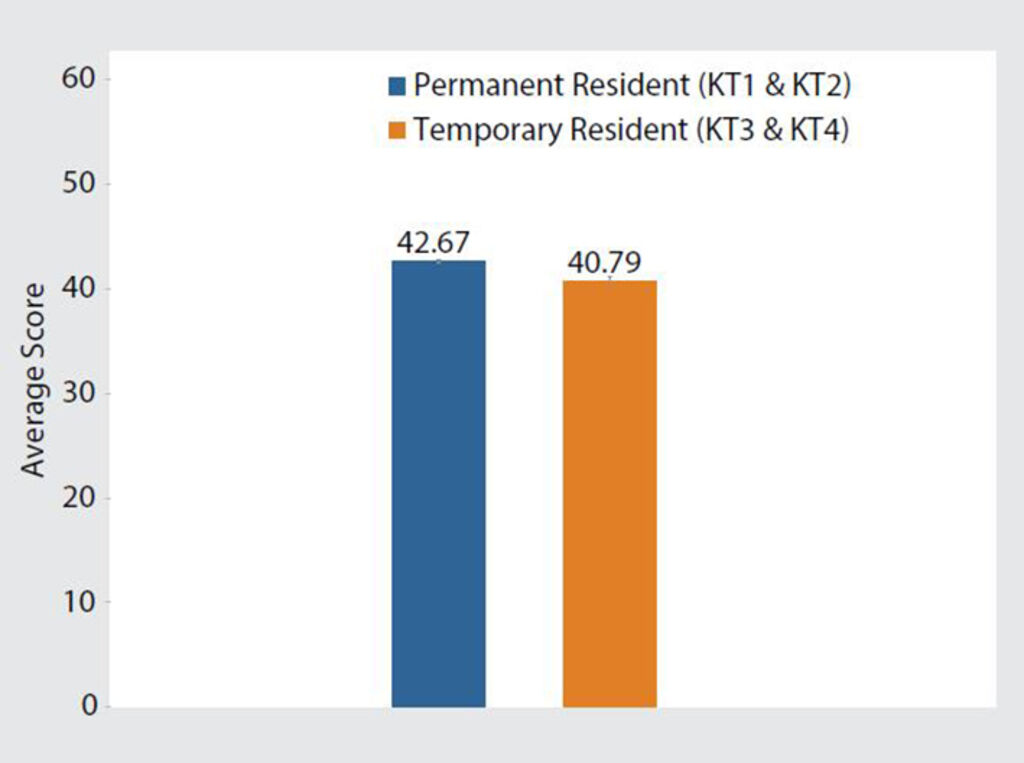

Regarding migrants’ evaluation of governance and public administration performance, their assessments in 2021 indicated they encountered sub-par local governance conditions and inferior public services compared to local residents. This trend continued in 2022, as shown in Figure 2. Migrants gave their destination provinces an aggregate PAPI score of 40.79, which is at the average level on the scale from 10 to 80 points, while permanent residents scored the same provinces at 42.67. The difference of nearly two points is both statistically significant and meaningful since the 95 percent confidence intervals do not overlap.

|

| Figure 2: Differences in governance and public administration as experienced by migrants in receiving provinces, 2022 |

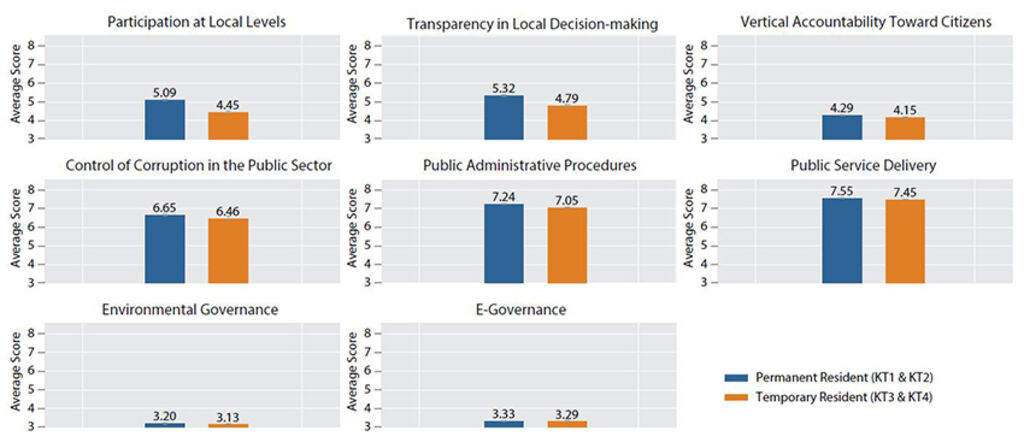

A deeper look into all governance and public administration dimensions, as experienced by the two groups in receiving provinces in 2022, reveals differences in all eight PAPI dimensions as seen in Figure 3. These resident-migrant contrasts were largest in the two dimensions of Participation at Local Levels and Transparency in Local Decision-making, similar to the 2021’s findings.[6]

|

| Figure 3: Differences in governance and public administration as experienced by temporary residents in receiving provinces, by dimension, 2022 |

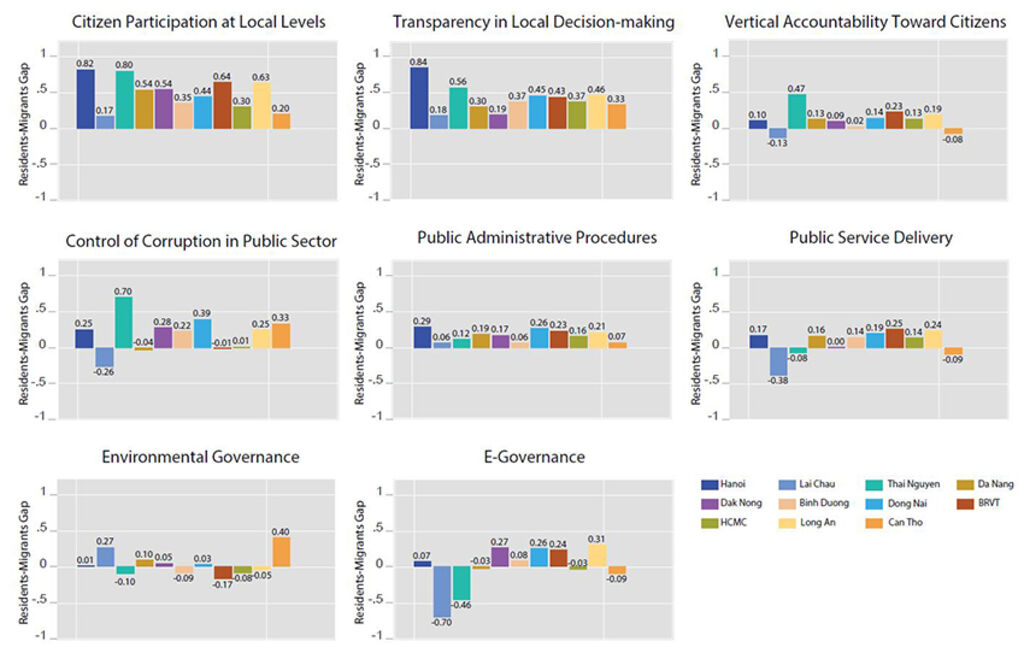

On how inclusive local governance and public administration performance is for short- and long-term temporary residents, the 2022 PAPI survey revealed profound differences in Participation at Local Levels and Transparency in Local Decision-making visible across all 11 receiving provinces (with Bac Ninh excluded due to data noises). The gaps in Hanoi are larger with more favorable feedback from residents in Participation at Local Levels, Transparency in Local Decision-making and Public Administrative Procedures. Gaps are smallest in Binh Duong. In Lai Chau and Thai Nguyen, temporary residents had more favorable feedback on E-Governance. Figure 4 shows the differences by receiving provinces.

|

| Figure 4: Differences in governance and public administration performance as experienced by migrants in receiving provinces, by province, 2022 |

Issues of greatest concern for internal migrants

With such differences, it is important to look into how a migrant status impacts their attitude toward priorities and economic situations. On one hand, migrants could be most vulnerable, working in jobs that separate them from families and facing challenges to access public services, such as schools for their children and hospitals. On the other hand, migrants may be more likely to have jobs in relatively high paying, industrial sectors.

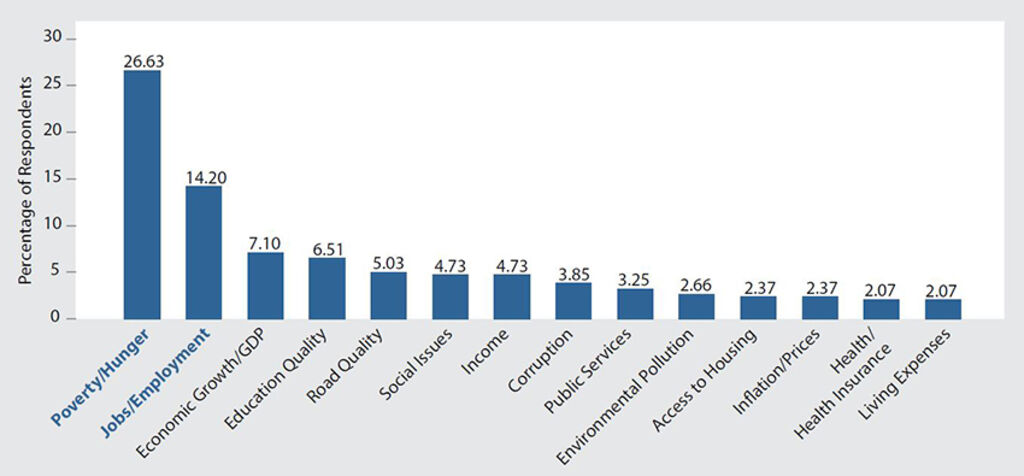

Figure 5 shows migrants’ issues of greatest concern. As with 2022 PAPI respondents who are permanent residents,[7] the most important issues for migrants in 2022 centered on their livelihoods: poverty and hunger first, jobs and employment second. Different from their permanent peers, migrants in receiving provinces were concerned about education quality for their children and this concern is among the top five issues.

|

| Figure 5: Issues of greatest concern for migrants, 2022 |

Figure 6 reveals these personal concerns were more pronounced, as the comparison of temporary and permanent residents in receiving provinces shows the former were substantially more concerned with poverty and employment. Also reflecting an interest in their economic well-being, migrants more focused on social issues, living expenses and education quality for their children.

|

| Figure 6: Differences in issues of greatest concern by residency status for temporary vs permanent residents, 2022 |

Meanwhile, as responses to a follow-up question in the 2022 PAPI survey about what services are made available for migrants in their receiving provinces indicate, migrants most frequently received support for access to health insurance and then to housing. It seems there are differences between what migrants were most concerned about and what governments of destination provinces could provide.

Figure 7 presents the estimated impact of migrant status, gender and ethnicity on respondents’ evaluations of their current and future economic situations, perceptions of changes in household economic conditions, and the national economic situation. As depicted in the figure, temporary residents have comparable views to permanent residents in their provinces, with one exception. Migrants were more positive about their future household economic prospects, with a score 0.12 higher on a 5-point Likert Scale question asking whether their future conditions would be: much worse (1), worse (2), no change (3), better (4), or much better (5). Thus, despite their personal economic concerns, migrants had a relatively optimistic outlook on their economic future. However, when it came to the national economic situation, migrants appeared less upbeat than residents.

|

| Figure 7: Impact of migrant status, gender, and ethnicity on economic attitudes, 2022 |

Preferred destinations and drivers of migration within Vietnam

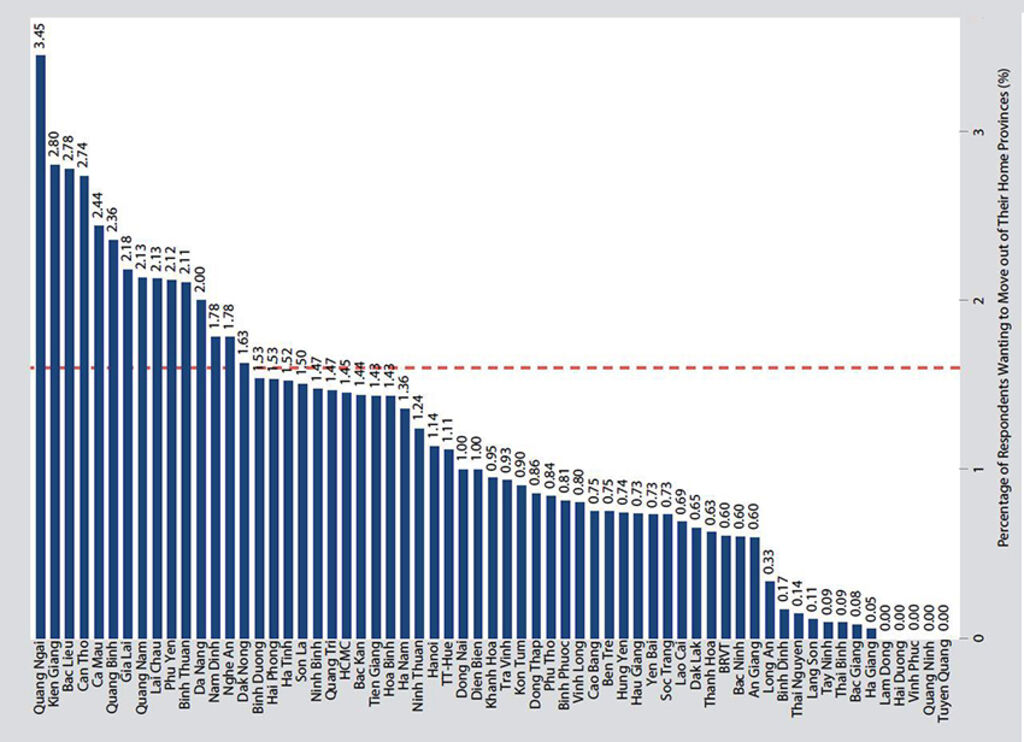

As in 2021, the 2022 PAPI survey looked into citizens’ interest in domestic and international migration. Compared to the 2021’s findings, the same number of respondents (about 1.6 percent) nationwide reported an urge to move permanently outside their home province in 2022, as shown in Figure 8.

|

| Figure 8: Percentage of respondents who want to move out of their provinces, 2022 |

Among all 63 provinces, Quang Ngai emerged as the province with the most citizens (3.45 percent) wanting to migrate domestically, replacing Dak Nong as the province with the greatest number of citizens wanting to move out in 2021. Then came the Mekong River Delta provinces of Kien Giang, Bac Lieu, Can Tho and Ca Mau. Interestingly, Can Tho became the sixth most preferred destination for many respondents in 2022 (Figure 9).

|

| Figure 9: Preferred destinations by percentage of respondents wanting to move, 2022 |

Meanwhile, the top five destinations for those wanting to move in 2022 in order of preference were Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Hanoi, Da Nang and Lam Dong, with Binh Duong replacing Can Tho to become the fifth most desirable destination in 2022. Meanwhile, the least preferred destinations in order of preference were Bac Kan, Dien Bien, Bac Lieu, Ha Giang and Hau Giang (Figure 9). Bac Lieu has been at or near the foot of the table since 2020.

Three key reasons for wanting to move in 2022 dovetailed with those in 2020 and 2021: family reunions (primarily for those who wanted to move to Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City), better jobs (to Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi and Da Nang) and a better natural environment (to Da Nang and Lam Dong) (Figure 10). The percentage of respondents wishing to migrate for better natural environment was on the rise again in 2022.

|

| Figure 10: Reasons for wanting to move from 2020-22 |

As found in 2020 and 2021, having family outside a province strongly predicted residents’ willingness to move, particularly for family reunions (Figure 11). In addition, men were more willing to move than women for nearly all reasons, except family reunions. Younger people were more likely to migrate, particularly for economic motivations, while the wealthy and educated were more likely to relocate for environmental reasons. Rural residents were less willing to move than urban residents for all of the reasons except economic ones.

|

| Figure 11: Drivers of migration motivations, 2022 |

According to the 2022 PAPI survey, there is a low willingness among Vietnamese citizens to migrate internationally. Only a small percentage (less than 0.8 percent) of respondents, specifically 124 people expressed a desire to live abroad. Among those who wanted to leave, the top three preferred destinations were the United States, Republic of Korea, and Australia.

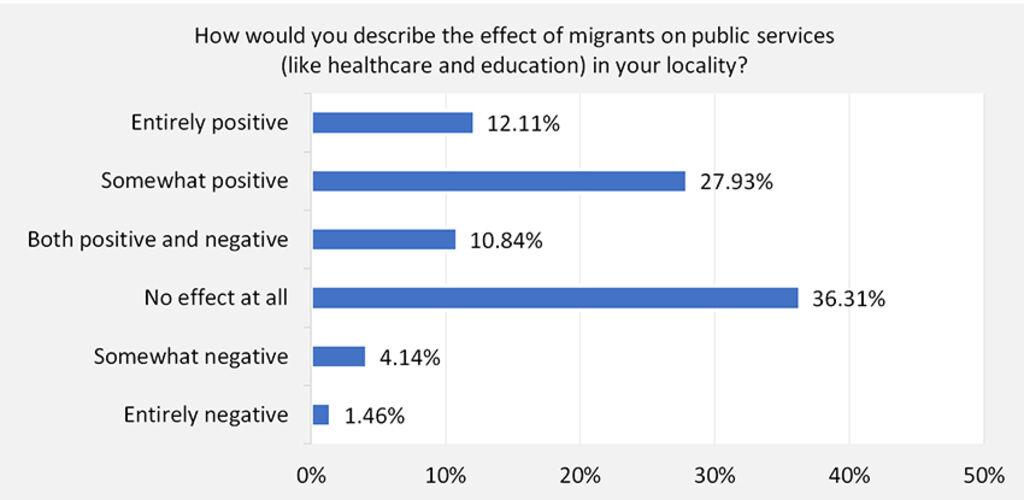

On how permanent residents view migrants’ effect on local public services in receiving provinces, as Figure 12 shows, about 5.6 percent said the effect was negative. Meanwhile, more than 36 percent said there was no effect at all, and about 40 percent were positive about migrants’ effect on local public services.

|

| Figure 12: Permanent residents’ assessment of migrants’ effect on local public services in receiving provinces, 2022 |

Conclusions and policy implications

As this article reveals, disparities in governance and public administration experiences remain apparent between temporary and permanent residents in receiving provinces. It reveals the consistent differences in temporary and permanent residences’ experiences since 2021, when PAPI officially included temporary residents in its annual survey samples.

The gaps varied by provinces of destination in 2022. Migrants in Hanoi tend to be a lot less inclusive in Participation at Local Levels, Transparency in Local Decision-making and Public Administrative Procedures than in other 10 provinces. The differences are felt less by migrants in Binh Duong province. Migrants in Lai Chau and Thai Nguyen had more favorable feedback on E-Governance in 2022 than those in other nine provinces.

The findings highlight the need for efforts from receiving provinces’ governments to bridge gaps to ensure migrants can fully realize their rights and achieve equality with residents of receiving communities in access to good governance and quality public services. This is crucial as temporary migrants are a significant source of human capital for provinces’ economic development. Besides, addressing migrants’ immediate concerns related to poverty, employment, and education can contribute to their overall well-being and facilitate their integration into receiving communities.

Finally, understanding patterns of internal migration is important for both central and local governments. Insights into why citizens want to migrate from their provinces of origin will help anticipate the levels of needs for basic public services such as healthcare, education, administrative procedures, housing and job information.-

[1] See General Statistics Office (2022). Report on socio-economic development indicators in Quarter 4 and Year 2022. Available at https://www.gso.gov.vn/bai-top/2022/12/bao-cao-tinh-hinh-kinh-te-xa-hoi-quy-iv-va-nam-2022/#_ftn2, accessed on January 15, 2023.

[2] This article is written by Do Thanh Huyen, UNDP Vietnam Policy Analyst, and substantially contributed by Dr. Edmund J. Malesky (Director of the Duke Center for International Development, Duke University, and the PAPI Chief Technical Advisor) and Dr. Paul J. Schuler (Senior Assistant Professor from Arizona State University and PAPI Data Quality Controller).

[3] See the article covering the national overview of 2022 PAPI findings published on the Vietnam Law and Legal Forum in May 2023 at https://vietnamlawmagazine.vn/poverty-economic-growth-jobs-road-quality-and-corruption-top-concerns-of-vietnamese-citizens-2022-papi-report-69826.html?utm_source=link.gov.vn#source=link.gov.vn.

[4] See General Statistics Office (December 2019). The 2019 Population and Housing Census at 0:00 hour, April 1, 2019, available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YK6iY-j0AfZTuip28Py2Gmz5P8zw04Rn/view. See Map 7.1 on p. 105.

[5] See Chapter 2 of the 2022 PAPI Report, CECODES, VFF-CRT, RTA and UNDP (2022), pp. 23-33 at https://papi.org.vn/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2022_PAPI_REPORT_ENG_E-book.pdf

[6] See the 2021 PAPI, CECODES, VFF-CRT, RTA and UNDP (2022), pp. 31-32.

[7] Ibid., p. 22.