This article takes initial steps in understanding causes and effects of land conflicts in Vietnam after the effect of the 2003 Land Law (the Land Law) and its subsequent amendments. It examines institutional arrangements that govern land rights security but may have created biases toward different land users upon conflicting land use purposes. The analysis also examines the values of the two available large sample surveys in Vietnam (the citizen perception-based Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) and the firm perception-based Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI)) in informing potential different treatments toward citizens and firms as land users. It suggests more balancing acts from local governments in response to both businesses and citizens in terms of land transparency and compensation policy.

Do Thanh Huyen, Policy Analyst

United Nations Development Program in Vietnam

Land conflicts: causes and effects

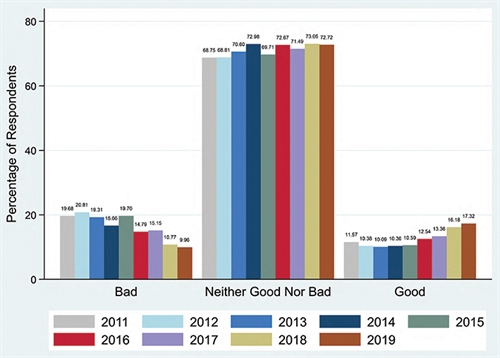

This section aims to analyze key causes and effects of land conflicts from the available data from PAPI and PCI. It provides some evidence to explain why land conflicts have risen in recent years in Vietnam. Figure 1 provides an analysis of what have triggered land conflicts in Vietnam. The analysis starts with the root causes of land conflicts from deep down to surface causes as gathered from various research papers and reports.[1] It also reveals negative short-to-medium term effects of land conflicts that require investigation by Vietnam’s political and government agencies.

Figure 1: An analysis of causes and effects of land conflicts in Vietnam

|

Note: The researcher’s own literature review and research with NEU and UNDP (2017).

Land conflicts since 2004 when the Land Law came into force and more recently have been triggered by the fact that land has become increasingly scarce and valuable due to Vietnam’s rising level of population, industrialization and modernization. Nonetheless, one of the root causes for land conflicts is closely associated with how different or similar the State behaves with the Market and the Society. Because of the needs for economic growth and national development, the market forces have been given more incentives in access to land compared to residential users.

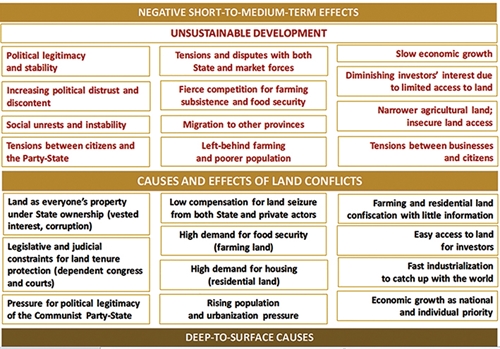

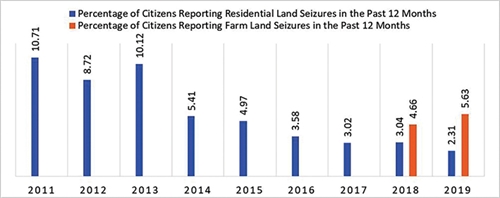

In many cases, and as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, households using residential and farming land seem to be more prone to land confiscation than firms. Although the proportion of households losing residential land was decreasing toward 2019, the proportion reporting that they lost farming land was on the verge of increasing (the PAPI research started collecting data about citizens’ experiences with farmland seizures in 2018). Often, suburban farmers are pushed to become urban dwellers or inter-provincial migrants living on alternative livelihoods that are much less sustainable. As the PAPI survey findings have shown, since 2015 when the question about what top three issues of greatest concern for citizens are, it has always been poverty and hunger that was ranked first.[2] Historically, poor farmers and peasants were those who fought for access to land and for national security. For now, people working in the farming sector and rural areas still account for the largest share of Vietnam’s population.

Figure 2: Citizens’ experience with land seizures (PAPI)

|

Source: PAPI data (2011-19)

Meanwhile, as Figure 3 shows, land expropriation risks facing businesses were on the downward trend, from more high likelihood (2.9 points) in 2011 to low likelihood (1.58 points) in 2019. The numbers indicate that things have improved since 2015 for firms, since the drop from 2.34 (which is still not relatively high) down to below 2 points for the past four years seems to indicate that firms feel relatively secure in their tenure.

Figure 3: Firms’ rating of risks of having land expropriation (PCI)

|

Source: PCI data (2011-19)

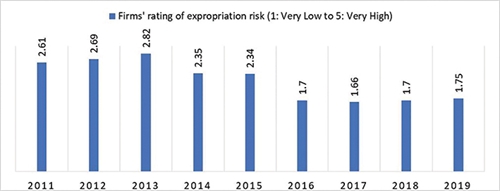

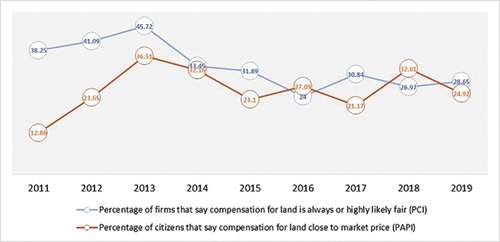

A key trigger of contemporary land conflicts in Vietnam is inadequately low compensation for both farming and residential land confiscated by the State for other purpose. When asked about compensation through the PAPI surveys over the past 11 years, inadequate compensation has been the key indicator that has lowered provincial scores for the land transparency sub-index. As shown in Figure 4, the trend for citizens’ experiencing compensation that was around the market price was rising toward 2013 and 2014, and then became steady toward 2019. Firms were happier with compensation prices than citizens before 2014 but shared the same observations since 2014.

Figure 4: Firms’ and citizens’ satisfaction with compensation for seized land

|

Source: PAPI and PCI data (2011-19)

Of more than 3,000 land-related complaints and denunciations the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment received and addressed within its authority between 2014 and 2018, 21 percent were about compensation.[3] The case studies conducted by UNDP in Vietnam and the NEU (2016) also provide real-life stories about upsetting citizens having had their land seized who kept staying in houses to demand “close-to-market land prices” for their land being converted into a satellite urban city near the capital city of Hanoi or the commercial hub of Ho Chi Minh City. Widespread community resistance in the case of the Ecopark City near Hanoi, the violent and deadly demonstration in Dong Tam commune, My Duc district, of Hanoi, and the large-scaled community protests in the case of Thu Thiem urban area in Ho Chi Minh City, which remain lingering challenges for the State to resolve, have been all about compensation.

Among the four provinces that are populous and receiving large numbers of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) and inter-provincial migrants, Hanoi and Bac Ninh (in the North), and Binh Duong and Ho Chi Minh City (in the South), the two in the South saw a sharp rise in citizen dissatisfaction with land compensation. Hanoi maintained the status quo, while Bac Ninh seems to have satisfied land losers’ expectation better. More importantly, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City stood out as localities where citizens have been much less satisfied with compensation for land confiscation for other purposes.

Easy or difficult access to land use rights certificates (LURCs) is another source of land conflicts between different users. Foreign and domestic investors are being welcome with easy access to land as one of the luring tactics for provinces in their competition for domestic and foreign investment, which is expected to yield higher economic growth and job creation. As findings from PCI over time (Table 1) show, domestic firms have stressed the importance of easy access to land through their increasing level of satisfaction with how local governments have responded to their need for land for industrial production or real estate development.

Table 1: Businesses’ perception of land access and tenure

| PCI Indicators (median values) |

2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Percentage of firms that own land and are in possession of an LURC | 65.55 | 73.96 | 69.74 | 55.38 | 60.14 | 54.96 | 59.24 | 50.12 | 59.55 |

| Percentage of firms that have completed land procedures in the last two years and have encountered no difficulties in land-related procedures | 47.54 | 39.10 | 44.04 | 41.62 | 24.30 | 39.13 | 42.42 | ||

| Percentage of firms that want to have LURCs but don’t have them because of complicated procedures and troublesome officials | 26.52 | 27.06 | 32.95 | 28.34 | 18.42 | 15.00 | 14.63 |

Source: 2011-19 PCI data

An examination of the common indicator between PAPI and PCI on the number of days firms and citizens could obtain LURCs shows different behavior by state agencies in charge of granting LURCs. Figure 5 shows that, after 2014 when on average firms had to wait up to 190 days for their LURCs, there was a huge drop in the waiting time for firms to barely 40 days. Meanwhile, citizens’ experience was consistent over the nine years, despite a fall from the peak in 2015 (89 days on the national average) and now citizens had to wait longer than firms to obtain LURCs (more than 50 days since 2013). It means that it has taken citizens more time to obtain LURCs than firms on average. Meanwhile, under the Land Law-guiding Decree 1 issued in 2017, both types of applicants should obtain LURCs within at most 30 days (Article 2.40).

Figure 5: Mean numbers of days firms and citizens waited to obtain land use rights certificates

|

Source: PAPI and PCI data (2011-19). PAPI = citizens’ perceptions and PCI = businesses’ perception.

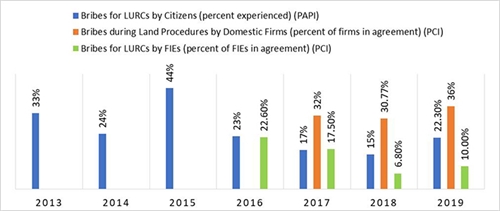

Such differentiated behavior by the State has led to public scrutiny of the motives and intentions of institutions that are mandated with legislative, judicial and executive functions. Those who have had their land seized for other use purposes may think the State and the Market have been in collision for someone’s interests, not for their or national development interests. Since 2013, findings from PAPI surveys have shown that bribes for land use rights have been steady (see Figure 6). This is also the case for domestic firms wishing to get access to land leases, as evident in the PCI findings. For foreign-invested firms, it seems fewer of them have had to pay bribes for LURCs. This might be attributed to a better bribe-controlling mechanism from the 2015 Penal Code that took effect in 2018 with a new ban on bribing foreign public officials (Article 364.6)[4].

Figure 6: Bribes for LURCs by citizens and businesses

|

Source: PAPI and PCI data (2011-19)

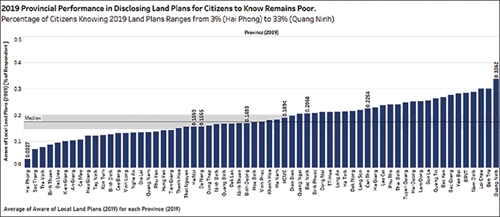

Information asymmetry about local land plans is an important trigger for land conflicts. It goes hand in hand with the lack of transparency in land use plans and land price norms and bribes for LURCs. Under the Land Law and the 2016 Law on Access to Information, local land plans must be posted for public views at all levels and online. However, access to local land plans remains limited, with about one-fifth of national respondents answering they were aware of local land plans since 2011 at the national aggregate level. PAPI findings by province in 2019 (see Figure 7) show the percentage of citizens knowing 2019 land plans ranging from 3 percent (in Hai Phong) to 33 percent (in Quang Ninh).

Among the four provinces in question, in 2019, only 15.5 percent of Hanoi citizens were informed about local land plans. The proportion in Binh Duong was 17 percent; in Ho Chi Minh City, 19 percent; and in Bac Ninh, 20.7 percent. Also, none of these four provinces improved much in making land plans better known to more than a quarter of the local population after five years. The findings show that Bac Ninh and Ho Chi Minh City did a better job in disclosing information about land plans to citizens than Hanoi and Binh Duong. Binh Duong, the heavily industrialized provinces with the highest inter-province migrants for labor and the largest investment inflows, was rated poorer in terms of land plan transparency, while the impact of local land planning on citizens in 2019 was much less beneficial than in 2014. This might explain, though indirectly, land conflicts involving large projects in Hanoi and Binh Duong in recent years.

Figure 7: Citizens’ access to local land use plans by province in 2019

|

Source: 2019 PAPI Data

Knowing where to get governments’ official land price frames is also important for citizens to evaluate whether the prices being offered for land being transferred to other users are equivalent to the market value. It is also a measure of whether local governments fix land prices at their own stake or at real market prices. Findings from 2014 and 2019 PAPI surveys show that fewer than half of all provinces made improvement in making information accessible for citizens. Among the four selected provinces, only Bac Ninh made some improvement, with about 15 percent more of the citizens knowing where to get information about local land price frames than five years ago. In Binh Duong, fewer people were able to get access to information in 2019 than in 2014. Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City made little move over the five years.

The Society as represented by individual and household users seems to have a limited say on land use plans. The 2011-19 PAPI survey results in Figure 8 show that, the percentage of respondents that had a chance to provide comments on local land plans dropped dramatically in 2015 after the effect of the Land Law. After going to the peak of barely 35.28 percent, the percentage was on decline again to 27.66 percent in 2019.

The findings presented above depict preferential behaviors toward firms as well as the information asymmetry as experienced by both firms and citizens. These are two of the causes of tensions among the State, citizens and firms when land governance is concerned. In fact, tensions between the State and citizens or between firms and citizens have been well-documented (see The Asia Foundation 2013 and UNPD and NEU 2016, for instance).

Discussions and policy implications

Fast economic growth for Vietnam to become a middle-income nation remains a top national policy priority, as the discussions on the 2021-30 socio-economic development strategy go on, especially at the arrival of the global Covid-19 pandemic. Whether the market forces will take over the development agenda in the socialist-oriented market economy remain open for further exploration.

For firms, land conflicts can pose serious risks in terms of costs of doing business and investment viability. This can be a result of social unrest and/or political instability in the medium and long terms if firms fail to negotiate with local land users as required by the Land Law. In many cases, firms try to avoid land conflicts with citizen users by requiring provincial governments to provide them with “clean and cleared” land as a prerequisite for investment.[5] Many provinces have welcomed investors for economic growth and political interests of local government officials by offering clear land plots, upon confiscation of land from individual land users. The differentiated behaviors by provincial governments as evidenced in this article speak to the preference given to investors, which in return is being seen as state-business collision for land taking from farming users for vested interest. Without government backup, investors, especially foreign-invested enterprises, would choose a place with more supporting incentives, including favorable land rental schemes for them.

The findings presented in this article imply more work to be done to improve land transparency for citizens, who play critical roles in securing the regime legitimacy and contributing to the sustainable development of Vietnam. Better law enforcement, better government responses to citizens’ expectation and feedback, robust evidence-based policy making and implementation, and more importantly active leadership from all government levels in civil service inspection will help create a more level playing field for the Society and the Market in relation with the State in land governance to mitigate potential conflicts when Vietnam attempts to enter a higher middle-income status.-