Pham Thi Duyen Thao, LL.D

Law Faculty

Hanoi National University

Judicial integrity constitutes a category with rich contents, which can boil down to the requirement of society for a clean judicial system with clean judicial officers devoted to the defense of common sense and justice. In specific terms, judicial integrity is demonstrated through such basic aspects as professional responsibility, honor and conscience, and combat against corruption to maintain a clean judicial system. Necessary guarantees for judicial integrity include an independent justice system and citizens’ access to justice, aiming to promote the responsibility of judicial bodies[1].

In Vietnam, in the course of building a law-ruled socialist state, the Party and State have charted out a judicial reform strategy aiming principally “to build a clean, strong and firm judicial system for the defense of justice and respect for and protection of human rights.”[2] This goal is guaranteed by “improving criminal and civil policies and laws, judicial procedures, strengthening the organization of judicial bodies in a scientific and synchronous manner, and heightening the independence, objectivity and law observance of every judicial body and title.”[3] On this path, we are approaching judicial integrity as a means of materializing the goal of building a law-ruled state. In the course of improving our policies and laws, it is necessary to study the country’s past criminal procedure law.

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le (the National Procedural Regulations of the Royal Dynasty or the Code for short), promulgated by King Le Hien Tong in 1777, is an original legislative achievement of the late Le dynasty. Its originality, as assessed by researchers, consists in its appearance as a separate procedural code in the then circumstances of Dai Viet (Great Vietnam) and the feudal Orient. The Code’s uniqueness also lies in its judicial ideology, including judicial integrity - a category which should have been guaranteed only in a law-ruled system.

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le was composed of 31 Regulations. The first Regulation sets forth general procedures while the subsequent ones provide specific legal proceedings for different types of affairs, like filing of lawsuits and complaints, adjudication time limits, legal costs, litigation for murder cases, litigation for land-related and robbery cases, and so on. The Code demonstrates basic, albeit initial, ideas of judicial integrity.

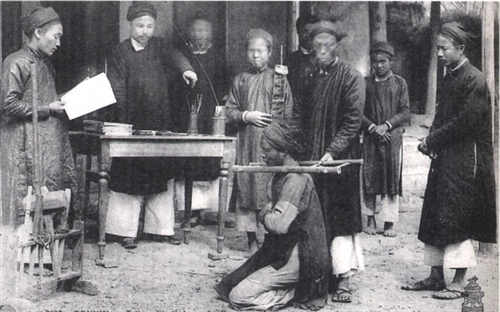

|

| A convicted criminal listens to the pronounced entence __Photo: Internet |

Professional responsibility and conscience of judicial officers to respect and protect human rights

Transparency, fairness and protection of people’s interests were regarded as the professional mission, responsibility and conscience of judicial officers under the late Le dynasty.

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le provides legal procedures in the spirit of defending justice and protecting human rights.

Generally, under the Code, competent authorities who commit wrongful acts against the people all face severe punishment as stated in the Regulations on litigation against repression, litigation against misappropriation, litigation against power abuse, etc.

It protects and rewards eye-witnesses, denouncers and courageous persons: “Those who pursue and arrest or truthfully denounce criminals shall be awarded with mandarin ranks, money, or relief from public duties, depending on important or minor cases. If unfortunately getting killed, their deeds shall be reported to local mandarins and responsible authorities for award of funeral money and certificates of merits. Those who cover up criminals shall be degraded or dismissed if they are mandarins, or punished for the crime of robbery or burglary if they are commoners...”[4].

The Code also severely punishes those who cover up or tolerate criminals, especially slanderers. “High-ranking mandarins, military or civilian, may not harbor robbers or burglars. If doing so, mandarins shall be degraded or dismissed, while commoners shall be punished as for the crime of robbery or burglary”[5]; and “All false reports or denunciations that give rise to litigations against others shall be subject to punishment by strokes of beating with a heavy stick....”[6].

Regarding reconciliation, Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le contains flexible provisions aiming to best protect lawful rights and interests of people. For less serious crimes such as deliberately causing slight injuries, the Code encourages reconciliation among the involved parties: “ If the injury is minor, the inflictor shall be admonished.”[7] Yet, reconciliation is disallowed for serious and complicated cases such as adultery and murder: “Those who commit adultery with well-founded evidence shall be punished in accordance with law without reconciliation”[8]; and “as murder cases fall under criminal law, the involved parties are not allowed to reconcile; even judicial mandarins may not permit reconciliation.”[9]

The Code does not permit reconciliation in murder cases because it aims to prevent other related law violations. This provision is of highly educative nature, demonstrating the spirit for justice. Criminals must be held accountable not only to their victims but also to the law and people: “... there have been cases of causing injustice for the purpose of robbing money; cases of killing people then clandestinely giving money and land to victims’ families for reconciliation without filing lawsuits; or cases of post-litigation reconciliation allowed by judicial mandarins, thus making sinners more domineering and helping rich criminals escape punishment under law. From now on, if the victim and the criminal make reconciliation in any case of injustice or murder with clear evidence, both parties shall be judged and punished under law...”[10]

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le demands judicial officers to adhere to the procedural principles while also providing exceptions so as to best protect human rights.

Every Regulation in the Code establishes the procedural order, time limits and statutes of limitation for each case. Specific time limits for settlement require both commoners and authorities to be accountable and active in their acts. They also express the royal court’s commitment to fulfill its duty to defend justice. Respect for the procedural order and time limits is an important measure to guarantee human rights as it prevents delay in the hearing of criminal cases and ensures interests of involved parties.

While the Code demands mandarins to strictly follow time limits set for adjudication, it says that delays that are on the part of people can be tolerated if they have justifiable reasons. These reasons may include “farming work in harvest time”[11] or “holding a funeral for a dead relative.”[12]

Regarding jurisdiction to hear cases, the Code lays down a general principle that all lawsuits shall be filed and heard according to the prescribed jurisdiction in order to ensure the procedural order and restrict abuse of power. “All complaints and lawsuits of people shall be settled according to regulations by local district mandarins, provincial mandarins, then royal mandarins. Lawsuits filed ultra vires shall not be accepted.”[13] However, the Code allows some exceptions aiming to ensure human rights and restrict injustice and loss caused to people. “All cases of suffering or injustice caused by authorities’ repression about which people do not know where and how to file their complaints, or cases already heard but unreasonably settled, may be filed through drum beatings.[14] In addition, “judicial officers may not obstruct the adjudication of filed cases; otherwise, they shall be punished in accordance with law.”[15]

As for the legal proceedings, Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le provides: “When adjudication is due, judges may not delay it and persons summoned for trial must be present.”[16] However, adjudication can be postponed in cases specified in the Code such as absence due to being on a working mission, a relative’s funeral, sickness or another plausible reason.[17]

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le heightens the judicial officers’ duty to protect human rights throughout legal proceedings

The Code attaches importance to the professional responsibility, honor and conscience of judicial officers. All of its regulations were designed in the spirit that competent authorities must uphold their responsibility throughout the hearing of cases. Protection of human rights of not only the victims but also of vulnerable parties in legal proceedings such as defendants, the accused and persons held in custody, is determined as the ultimate goal.

The Code clearly determines relevant responsibilities of judicial officers at various procedural stages. At the stage of receiving a petition, competent persons shall guide the petitioner how to write the petition properly, which must state the grounds and evidence (such as contracts for land-related litigation, wedding presents for marital litigation.[18]) For cases of murder, each petition may state no more than two perpetrators and four assaulters and must name the accused....”[19] For falsely denounced or minor cases causing no or little damage, judges may not accept them but may summon persons concerned for admonition.

The Code also make detailed provisions on scene investigation and autopsy, which “shall be carried out immediately without delay”[20] with exhibits and scenes strictly protected. Written records must be made and submitted to higher-level authorities for safe keeping.

Arrests, according to the Code, must be made by competent persons who must present clear evidence to district-level mandarins. In their turn, these mandarins shall send official letters to commune chiefs for notification to persons to be arrested. Failing to do so, they shall be held accountable and “people may file their complaints or denunciations against judicial officers.”[21]

During adjudication, judicial officers must base themselves on the law to judge the cases, citing relevant official legal documents.[22]

The spirit of combating corruption to ensure a clean justice system

The idea of judicial integrity in Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le is clearly manifest in its regulations bearing the anti-corruption spirit to ensure a clean justice system and interests of innocent people: “People of rank and fashion, who suppress others and offer bribes to judicial mandarins... shall be sentenced to degrading or dismissal.”[23]

The Code prevents corruption right from the stage of arresting persons related to litigation cases: “Any mandarins in charge of arresting persons who are reported to commit harassing acts shall be judged and punished.”[24]

Regarding litigation costs, Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le provides: “Defendants shall pay litigation costs for the plaintiffs and the complained persons.” This provision not only helps reduce state budget spending but also has preventive and educative effect. Expenses, including meals, for district mandarins “shall be paid by the instigators and their accomplices...”[25] But commune and district mandarins “may not ask for investigation, examination and meal money from the former’s relatives”. If doing so, “they shall be penalized in accordance with law.”[26]

According to the Code, the compensation paid to victims “shall not be collected arbitrarily from instigators and their accomplices by victims’ relatives or villagers...”[27].

The Code also sets specific court fee amounts and their payment time, and investigation and examination costs in order to prevent over-collection.

Besides, Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le states that annual review of adjudication work shall be conducted according to the principle that the superior shall review adjudication work by the subordinate: “At the end of every year, provincial mandarins shall review adjudication work of district mandarins; ministerial-level mandarins shall review adjudication work of provincial mandarins...”[28]

Measures to guarantee judicial integrity

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le initially provides a mechanism to ensure independence of parties involved in legal proceedings

The decentralization of jurisdiction and areas of adjudication provided in the Code contributes to creating a certain degree of independence for judicial officers. Cases, matters and areas falling under the jurisdiction of every level and every body were listed and specified by the Code, although without true separation as seen in modern procedural law. Judicial officers who fail to perform their assigned or decentralized duties and powers in the receipt and processing of lawsuits, investigation and adjudication shall be held accountable before law.

Especially, the Code aims to protect the judges’ independence in adjudication and heighten the investigators’ impartiality so as to restrict the abuse of power or self-seeking: “Judicial mandarins may neither interrogate without superior mandarins’ order, nor privately accept to help litigants, receive lawsuits, make arrests and conduct search.”[29]

It also places importance on judges’ rulings and arguments, which constitutes a precondition for judicial independence. In their judgments, judges “shall reason the wrong and the right for the involved parties to understand...”[30] This also testifies to the judges’ committed responsibility for their verdicts.

Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le initially sets a mechanism to ensure people’s access to justice with a view to promoting the responsibility of judicial bodies

Such mechanism is expressed through regulations on “a reasonable time limit” required for the settlement of lawsuits. This “reasonable time limit” is referred to in the Code in various procedural aspects and stages. First, it provides that state bodies must make public their timetables for reception of citizens and handling of affairs: “Monthly on working days, judicial offices must post up notices for litigators to know...”[31], and “on the first day of every month, judicial offices must post up the adjudication days in that month for people involved in litigations to know and come for settlement.”[32]

The Code also prescribes time limits for making arrests such as “half or one day” for arrests ordered by district mandarins, and “up to seven, 20 days or even a month” for arrests ordered by ministerial-level mandarins, depending on short or long distances[33].

For cases of murder, it clearly sets time limits for scene investigastion in order to ensure the objectiveness of the cases: “Commune and district mandarins shall immediately go to the scene for investigation... within no more than two or three days and must not deliberately delay.”[34]

Particularly, the adjudication time limits are specified for every type of case, which the judges must strictly observe if they do not want to be penalized: “The adjudication time limit is three months for cases related to land, robbery or burglary; four months for murder cases; and two months for uncomplicated cases related to civil status, marriage or public disorder. Judges shall be degraded or dismissed if they delay the adjudication for one month or three months or over, respectively.”[35]

Values of Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le

Despite its limitations such as non-separation of executive and judicial powers (commune chiefs would perform both the administrative management and the adjudication of lawsuits in their communes), permission for torture to take statements, design of legal proceedings based on types of cases, etc., the biggest value of Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le is its spirit. The late Le dynasty’s lawmakers designed it in the spirit of establishing a system of procedural rules for judicial officers to strictly comply with, and to constantly uphold their responsibility to protect lawful rights and interests of people, especially vulnerable groups, in legal proceedings.

This spirit has made some points of the Code transcend time in terms of the content and ways of building the regulations in the Code. Its most prominent point is a focus on the public-duty responsibility and legal liability of competent authorities, which were always placed in correspondence with the interests of the parties involved in legal proceedings and of people in general. Most of its regulations were designed to include manners of conduct and specific measures to handle violations committed by judicial officers in legal proceedings as a guaranty for maintaining the effect of the Code. This originality and the talent of the late Le dynasty’s lawmakers made the Code bear the spirit of the rule of law, truly reflecting the mission of a procedural code as decreed by King Le Hien Tong upon the promulgation of the Code: “Regarding litigation, the core lies in cleanness and fairness... so that commoners can rely on.”[36]

Although not really compatible with the international standards on judicial integrity, the spirit of judicial integrity in Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le not only is of significance in the nation’s procedural law history but also has modern values that are worth to inherit in the course of advancing the judicial reform.-