Institute for Sustainable Development (National Economics University) and United Nations Development Program

|

| The seminar themed “Internal Migration in the Red River Delta and the Mekong River Delta: Current Issues and Policy Implications” held by the National Economics University in coordination with UNDP Vietnam__Photo: UNDP |

Abstract

Internal migrants in the Red River Delta (RRD) and Mekong River Delta (MRD) encounter significant challenges related to social welfare, housing, education, and integration. A recent study titled “Internal Migration in the Red River and Mekong River Deltas: Current Issues and Policy Implications,”[1] commissioned by the Institute for Sustainable Development (the National Economics University - NEU) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Vietnam, highlights the issues. The research covered nine original and destination provinces in the RRD and MRD, providing insights into the drivers of migration and the obstacles faced by migrants in their daily lives. This article presents key findings regarding the drivers of migration; and the challenges and opportunities faced by migrants regarding their livelihood, access to public services, and social protection. It also provides an extensive list of recommendations for policymakers and practitioners to consider when designing and implementing policies and solutions to guarantee the rights of migrants to be recognized, protected and respected.

Internal migration push and pull factors in the two deltas

Since the “Doi moi” (Renovation) policy was initiated in 1986, Vietnam has achieved remarkable results in economic growth and development, transforming the country from a poor to a lower middle-income country in 2009. However, the next stages of economic development require deeper reforms in resource allocation within the country. Greater economic and social development not only requires the efficient exchange of goods and services, but is also reflected by the mobility of people. As part of the development path, dynamics such as industrialization, urbanization, poverty, and demographic changes have posed great challenges, also related to the management of within-country migration. In the short term, within-country migration represents the more efficient allocation of labor conducive to growth, but, in the long run, unplanned migration might severely affect wellbeing and the quality of life of migrants, widening the gaps between migrants and permanent residents. This creates a critical policy challenge given the outdated household registration system (the “ho khau” system), and low preparedness of local authorities in dealing with internal migration.

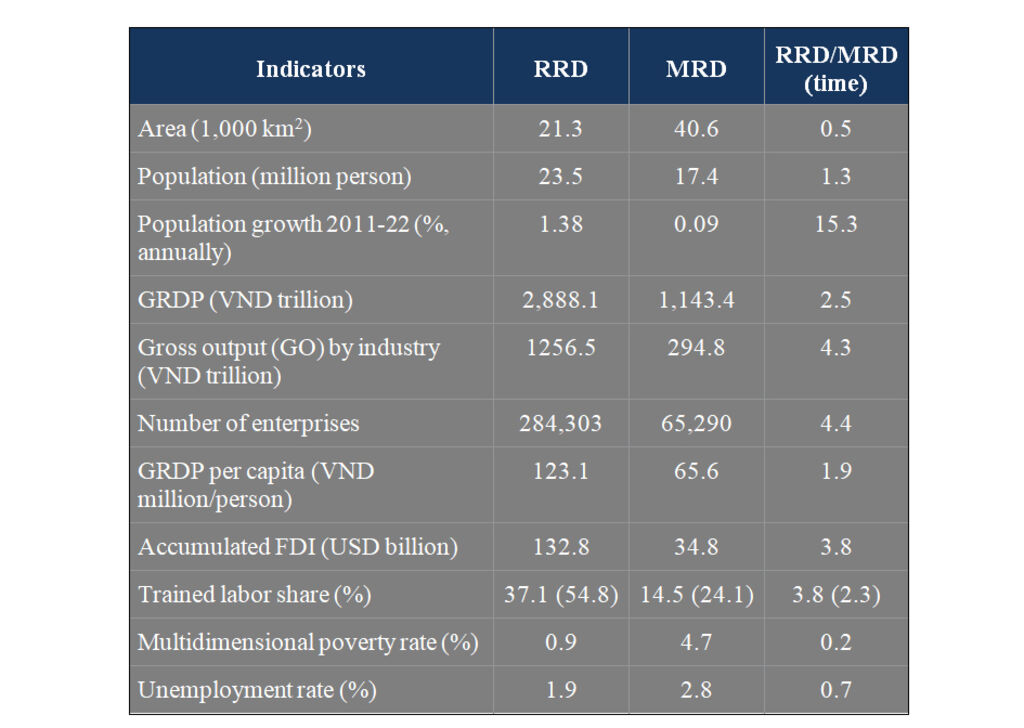

Some regions in Vietnam have experienced a very dynamic mobility of people, notably the RRD and MRD regions. Although they are similar in the population size, the former experienced net outflows of people, and the latter exhibited net inflows. As presented in Table 1, the two deltas also differ in their socio-economic conditions, where the MRD is under-industrialized, with a dominant economic role played by the agri-aquaculture sector. Meanwhile, the RRD is densely populated and highly industrialized, attracting high foreign direct investment (FDI) directed to big industrial sites and manufacturing facilities coexisting with many small-sized and family-owned businesses. These different socio-economic conditions result in diverse pull and push factors for migration dynamics in the two regions. In this context, a greater understanding of the living and working conditions of migrants will provide insights into local governments’ preparedness to effectively manage migration flows and ensure that migrant people are not left behind.

Table 1: “Push” and “Pull” factors in the Red River and Mekong River Deltas

|

| Source: General Statistics Office, 2023 |

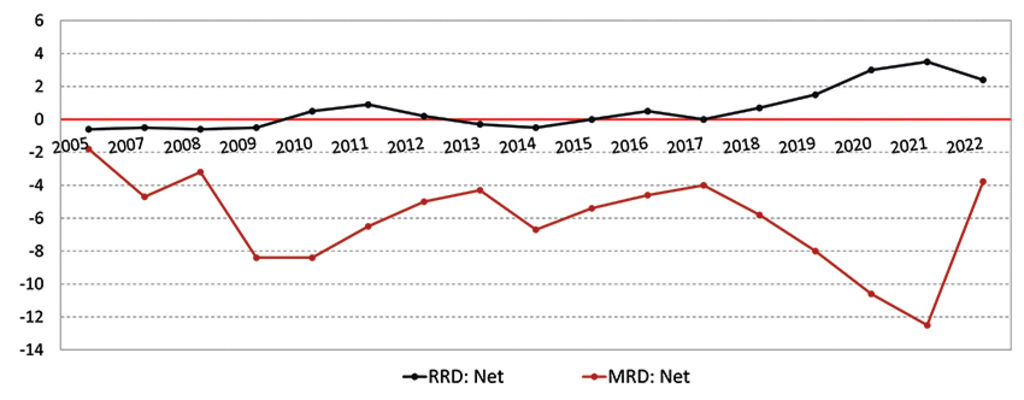

According to the 2023 statistics from the General Statistics Office (GSO), during the period from 2018 to 2022, the MRD region persistently experienced a net outflow of people, while the RRD region encountered a net inflow of people (see Figure 1). Among provinces in these two delta regions, Soc Trang, Ca Mau, Tra Vinh, and An Giang exhibited the largest outflow of people, and Bac Ninh was the largest recipient of people nationwide in 2022. According to the survey on people mobility and family planning, also conducted by the GSO, in 2021, urban-urban migration accounts for most within-country migration, 33.8 percent, followed by rural-rural migration, 32.5 percent, and rural-urban migration, 24.6 percent. Most migrants are young, with the most dynamic mobility cohort of 20-24 years old, then 25-29 years old and 15-19 years old. The top drivers of migration are economic reasons, family union, education, and living environment, which are consistent with the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) survey findings from 2020-23.[2]

|

| Figure 1: Positive net migration in RRD vs. negative net migration in MRD, 2005-22 |

Furthermore, the PAPI surveys in 2020-23 showed persistent disparities between migrant and permanent residents’ assessment of destination provinces’ performance in governance and public administration performance. Since 2020, the PAPI surveys have collected feedback from migrant citizens (both short-term and long-term) on the drivers of migration and their perception and experiences on the quality of public administration and public service delivery in 12 provinces with net inflows of migrants. Among them, Hanoi and Bac Ninh are in the RRD, and Long An and Can Tho are in the MRD. All the other provinces are outside the two river deltas. The PAPI surveys have data from the migrants’ host provinces, thus lacking insights about the migrants’ home provinces that could underline the push factors in the migration decisions. Thus, the findings from the qualitative study presented in this article help give insights into why people opt for leaving their original provinces.

Internal migration is a multi-faceted issue that calls for examining it from different angles and stakeholders, both from citizens and public officials. In addition, besides the driving forces of industrialization, urbanization, poverty, and demographic changes, the drivers of migration decisions might come from recent phenomena of lifestyle and climate change, particularly in the MRD. Historically, both internal and cross-border migrants have played a crucial role in socio-economic development. However, their contributions hinge on the existence of fair and inclusive migrant management mechanisms that uphold and promote migrant rights in host communities. Considering the recent enforcement of the 2020 Residence Law and roll-out of the National Population Database, it is therefore important to have insights into what internal migrants confront at both original and destination places.

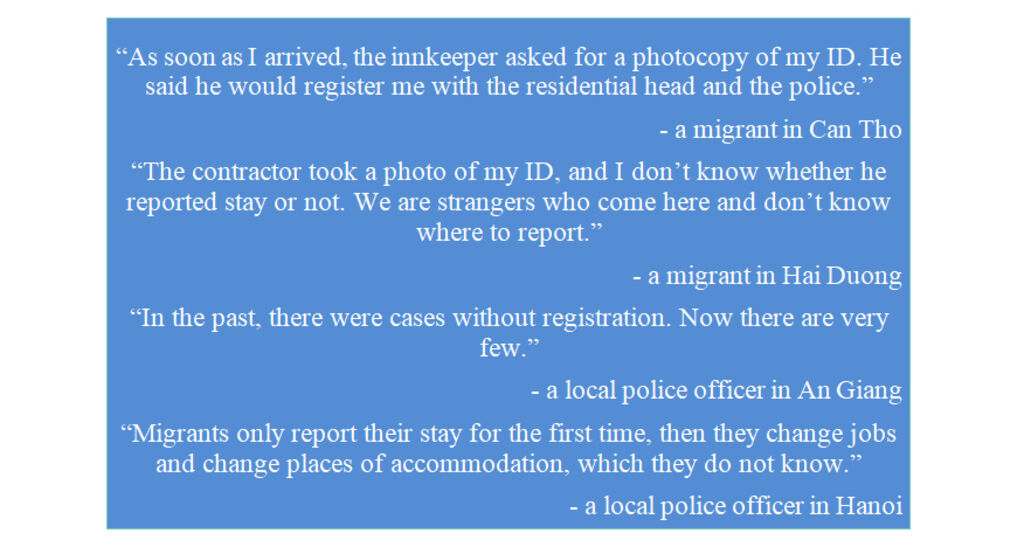

Internal migrants featured in this article are those living in a different province for one month or more, or for less than one month but with the intention to stay longer or having lived in a different province for a total duration of more than one month. Also, there are two types of internal migrants: registered migrants (those staying for more than one month with temporary residence registration, or for less than 30 days with a staying report), and unregistered migrants (those staying for more than 30 days without temporary residence registration, or for less than 30 days without reporting their stay).

Tales about internal migration governance

To arrive at the main findings presented below, the research team conducted interviews with 67 public officials and civil servants from the Departments/Divisions of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs, commune/ward People’s Committee officials, and commune/ward police in nine provinces, including four provinces in the RRD (i.e., Hanoi, Bac Ninh, Hai Duong, and Nam Dinh), four provinces in the MRD (i.e., Can Tho, Long An, An Giang, and Soc Trang), and one province in the Southeastern region (i.e., Binh Duong which receives many migrants from the MRD). Direct interviews with 96 interprovincial migrants and five families with members who had migrated out of their original provinces were also conducted, in addition to 16 focus group discussions with inter-provincial migrants. The interviews and focus discussion groups with the migrants focused on the reasons and processes of migration, residence registration, employment, living conditions, access to public services, community integration, and migration strategies. Furthermore, the research team analyzed statistical data on various socio-economic variables and migration flows in the two deltas to gain a deeper understanding of the research area and the “push-pull” factors of migration.

The key findings from the study are the followings:

· Migration in the RRD is significantly influenced by “pull” factors, whereas migration in the MRD is primarily driven by “push” factors related to economic and social aspects. Migrants have not clearly identified climate change as a direct cause of their migration.

· The rural-to-urban migration flow remains the predominant trend in both deltas; however, rural-to-rural migration in the RRD and urban-to-urban migration in the MRD represent the second largest flows. The trend of relocating industrial production closer to rural areas is expected to alter migration patterns shortly, particularly in the MRD.

· Migrants to the RRD are inter-regional, primarily originating from Northern midland and mountainous provinces, to seek employment opportunities. In contrast, most migrants to the MRD are intra-regional, mainly from neighboring provinces, to look for higher-income job opportunities, with climate change acting as an indirect push factor.

· Many migrants are not well-informed about their rights and obligations regarding temporary residence registration and residence notification. However, they generally comply with these requirements when requested. More importantly, migrants do not fully understand the need of temporary residence registration for accessing social protection systems.

|

· Migration management is under meticulous control by local authorities in the MRD. However, local authorities in the RRD find migration management overloaded.

· Coordination between registration and labor management authorities is inadequate, as registration authorities have not shared data on laborers and children migrants. This lack of data prevents labor management authorities from conducting effective forecasts of the needs for school, healthcare, housing, and budgeting to meet increasing demands.

· Policies related to migrants are set out in various legal documents and regulations, with the level of implementation varying across localities. Provincial policies often distinguish between permanent and temporary residents, with many policies only applicable to permanent residents.

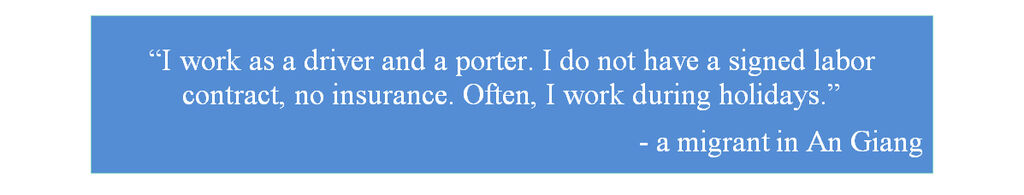

· Most migrants in the study sample do not receive sufficient social welfare benefits such as health insurance and social insurance in their new locations. Employed migrants in low-skill positions in businesses have labor contracts; but, most of them work overtime and receive little or no benefit. Many are exposed to unstable jobs or frequent job changes. Meanwhile, seasonally hired or freelance migrants have no labor contracts, low or no benefits and, seasonal work, and a high risk of job change and/or workplace relocation.

|

· Many migrants experience material deprivation, poor mental wellbeing, limited social lives, low income, difficult living conditions, and a lack of family support. They have access to poor quality housing because of cheap rents and temporary accommodation “just for sleeping”. Many also are separated from their families, especially their children and spouses. They almost have no recreational activities at their temporary residence places.

|

· There are gender inequalities in the work and lives of migrants, notably in three aspects: (i) female migrants are less likely to undertake jobs requiring mobility and physical strength; (ii) female migrants are more willing than their male counterparts to accept poor working conditions to secure employment and income; and (iii) female migrants face greater psychological, social, and community integration challenges than male migrants.

· Many migrants encounter difficulties accessing public education services for their children. Access to public preschool and primary education is particularly challenging for children from migrant households in the RRD. There is a serious lack of public kindergartens for children of internal migrants in destination provinces. The primary schools are too often overcrowded. Any available space in public schools is reserved for children of citizens with permanent residence or long-term temporary residence.

|

· Migrants rarely participate in community meetings and are involved in decision-making processes and community gatherings in their places of temporary residence. Most do not exercise their voting right at their temporary locations. Additionally, many community integration activities for migrants are limited due to cultural and lifestyle differences.

· Most migrants in the study sample do not possess a clear migration strategy, as their plans depend on job-seeking opportunities and security. In the short run, they depend on jobs and income. In the long run, they depend on the stability of employment, life integration, and housing. Home return is the last-resort option for those interviewed.

|

Policy implications and recommendations

Based on the results of field research and the best practices observed in the sample provinces, below are key policy implications and actions for policymakers and practitioners to consider. The suggested courses of policy action focus on ensuring three basic rights for internal migrants in destination localities: recognition, protection, and community integration.

Recognition and enforcement of the rights of migrants. Recognition and enforcement of the rights of migrants are essential for protecting their interests and needs. First, it should be explicitly acknowledged that migration is an inevitable socio-economic phenomenon that cannot be reversed. Improving both the material and spiritual wellbeing of migrants, as well as supporting and protecting their social welfare, should be a consistent policy priority. Second, policies should be designed to ensure equal rights and obligations for both permanent residents and migrants. Third, relevant authorities should promote and protect the rights and benefits associated with temporary residence registration, emphasizing the roles of landlords, labor contractors, and village leaders at destinations. Fourth, authorities need to enhance their responsibility to explain and guide local officials, including civil servants, police, and public administrative service providers at the commune level.

Strengthening coordination between residence management agencies and migrants-related management agencies. Strengthening coordination between the agencies is crucial to ensure data are shared effectively. This will facilitate timely inputs for formulating policies and plans to support and protect migrants. Specifically, three courses of action should be undertaken: (i) ensure and evaluate the effectiveness of coordination between agencies involved to develop methods related to population data collection, and electronic identification and authentication to support national digital transformation from 2022 to 2025, with a vision extending to 2030; (ii) promulgate and implement an inter-sectoral coordination plan that considers the needs and rights of migrants concerning housing, education, health, and social security; and (iii) integrate internal migration into strategies, local socio-economic development plans, and public budgeting processes to anticipate future internal migration flows and effectively manage expected migration flows.

Increasing opportunities for formal employment for migrants. To ensure social welfare services and protect the wellbeing of migrants, four solutions derived from the research findings are proposed. Firstly, labor management authorities should oversee the hiring and employment of workers, particularly regarding contractual arrangements between employers and employees in their respective localities. Secondly, relevant authorities and labor supply firms should provide information about labor markets in destination areas. In the RRD, it is particularly important to provide timely information to migrants from Northern midland mountainous provinces; in contrast, in the MRD, higher attention should be focused on migrants moving between rural areas within the region. Thirdly, migrants should receive skill development training, vocational training, and professional knowledge in both origin and destination provinces. Fourthly, local authorities should facilitate the transition of migrant workers from informal to formal employment sectors as a strategic long-term plan.

Increasing access to housing for migrants. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and Ministry of Construction should improve the land planning process to release house construction permits or ease renovation and maintenance of existing works in order to ensure decent housing for low-income earners, regardless of whether they are permanent or temporary residents. Local authorities receiving migrant workers should diversify the forms and types of housing available for workers (e.g., sales, rental options, or housing subsidies). Additionally, relevant authorities need to standardize and oversee minimum conditions for rental housing to ensure health safety, privacy, and fire prevention for tenants.

Managing migration driven by push factors and encouraging circular migration in the MRD. Managing migration driven by push factors is a major concern in the MRD. Issues such as poverty reduction, lack of vocational training for workers, unemployment, and the need to improve social welfare are key challenges. Circular migration can help resolve employment issues without disrupting lives or placing undue pressure on education systems, housing availability, public administrative services, or social welfare at destinations. To facilitate circular migration in the MRD, relevant authorities in the region should: (i) facilitate the creation of decent jobs in the agricultural and rural sectors to retain workers within the region; (ii) effectively implement multidimensional poverty reduction policies alongside social welfare programs; and (iii) develop mobility networks to improve transportation and connectivity for daily commuting within the MRD.

Encouraging network-based migration. Network-based migration involves utilizing social capital to assist individuals in moving, transitioning, and adapting to new contexts at their destinations. This approach enhances job stability, living conditions, access to public services, mental wellbeing, and community integration for migrants. To promote network-based migration effectively, it is important to: (i) encourage young migrants to relocate with their nuclear family members; (ii) motivate migrant workers to migrate within community groups that share customs, cultural values, and lifestyles; and (iii) strengthen the responsibilities of labor supply companies, employers, and labor unions in facilitating connections among migrants within community groups at their destinations.

Supporting migrants, especially inter-regional migrants in the RRD, to integrate into communities at destinations. The study findings underscore the important roles played by local government authorities, migrants, labor supply companies/contractors, and local communities at destinations in facilitating community integration for migrants. In the RRD, provincial authorities from the host provinces should openly share information regarding labor demand while coordinating with their counterparts in migrants’ home provinces in Northern midland mountainous regions. Migrants should be encouraged to proactively seek information to facilitate their integration into local communities at their destinations. Employment agencies ought to provide information about socio-economic conditions and cultural contexts at these destinations for hired workers. Local communities should slightly change their perceptions and treat migrants as members of their communities by involving them in local activities while respecting their customs and cultural values. Local authorities and civil society organizations are key stakeholders in facilitating and stimulating this social integration process.-

[1] This article is an excerpt from the Institute for Sustainable Development - ISD (National Economics University - NEU) and the United Nations Development Program - UNDP (2024) Internal Migration in the Red River and Mekong River Deltas: Current Issues and Policy Implications, a working paper by NEU-ISD and UNDP in Vietnam in the series of policy discussion papers on governance and participation. Hanoi, Vietnam: September 2024. For more information about the study, visit https://papi.org.vn/eng/di-cu-noi-dia-o-dong-bang-song-hong-va-dong-bang-song-cuu-long-van-de-hien-nay-va-ham-y-chinh-sach/.

[2] See the 2020-23 PAPI Reports at https://papi.org.vn/eng/bao-cao/.