Revision of the 2003 Criminal Procedure Code (the Code) has become imperative after more than ten years of implementation, especially after the new Constitution is promulgated in 2013 with many new provisions on human rights in criminal justice. This article gives an overview of prominent constitutional provisions on human rights and provides recommendations on revision of the Code in light of the new Constitution.

Trinh Xuan Thang, LL.M

State and Law Faculty

Politics Academy Region IV

Development of human rights in the new Constitution

The new Constitution shows a special respect for human rights. With the largest number of articles (36 articles), Chapter II on Human Rights, Fundamental Rights and Obligations of Citizens clearly distinguishes human rights from citizens’ rights, using the word “everyone” for human rights and the words “citizens” and “every citizen” for citizens’ rights.

For the first time ever, the Constitution lays down the principle of limitation on rights:

“Human rights and citizens’ rights may not be limited unless prescribed by a law solely in case of necessity for reasons of national defense, national security, social order and safety, social morality and community well-being” (Clause 2, Article 14).

Regarding criminal justice, the Constitution stipulates in Article 31: “A person charged with a criminal shall be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to a legally established procedure and the sentence of the court takes legal effect.”

Comparing with the provision of the 1992 Constitution that “No one shall be regarded as guilty and be subjected to punishment before the sentence of the court takes legal effect,” the new provision is better because in addition to a legally effective sentence of the court, it requires proving a person guilty according to a legally established procedure in order to limit or deprive of his human rights, especially freedom of body and right to free movement. Furthermore, the new Constitution specifies conditions for limiting human rights:

“No one may be arrested without a decision of a people’s court, or a decision or approval of a people’s procuracy, except in case of a flagrant offense. The arrest, holding in custody, or detention, of a person shall be prescribed by a law” (Clause 2, Article 20).

|

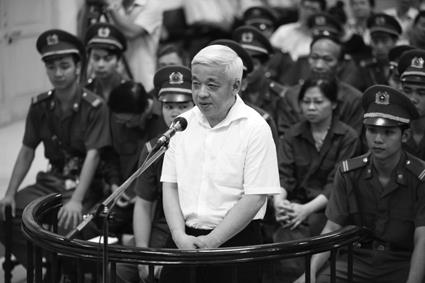

Defendants at the court hearing for their irresponsibility causing a serious traffic accident between a train and cars in Dong Nai province __Photo: Sy Tuyen/VNA |

The new Constitution adds some new human rights, such as the rights to conduct scientific or technological research, or literary or artistic creation, and to enjoy the benefits brought about by those activities, enjoy and access cultural values, participate in cultural life, use cultural facilities, and donate tissues, organs or body in accordance with law. It also reaffirms and develops the human rights already provided in the 1992 Constitution, such as rights to life, inviolability of body and private life, legal residence, freedom of belief and religion, to lodge complaints and denunciations, freedom of enterprise (in the sectors and trades that are not prohibited by law). For example, the new Constitute honors the right to defense as a human right, saying:

“A person who is arrested, held in custody, temporarily detained, charged with a criminal offense, investigated, prosecuted or brought to trial has the right to defend himself/herself in person, or choose a defense counsel or another person to defend him/her” (Clause 4, Article 31).

As a result, not only those against whom criminal cases are instituted or who are officially charged (under the 1992 Constitution), but also persons arrested, including those who are caught red-handed, held in custody or detained, involved in an investigation (under the new Constitution) may defend themselves or ask defense counsels to defend them in criminal proceedings.

The new Constitution prescribes more clearly the responsibility of state agencies to guarantee human rights: “the Government shall protect the rights and interests of the State and society, human rights and citizens’ rights” (Clause 6, Article 96); “people’s procuracies have the duty to safeguard the law, human rights, citizens’ rights” (Clause 3, Article 107); and “people’s courts have the duty to safeguard justice, human rights, citizens’ rights” (Clause 3, Article 102).

How human rights are safeguarded by courts is also more specifically provided. If the court illegally infringes upon human rights, it must pay compensations. Under the new Constitution:

“A person who is illegally arrested, held in custody, temporarily detained, charged with a criminal offense, investigated, prosecuted, brought to trial or subject to judgment enforcement has the right to compensation for material and mental damages and restoration of honor. A person who violates the law in respect of arrest, detention, holding in custody, laying of charges, investigation, prosecution, trial or judgment enforcement, thereby causing damages to others, will be punished in accordance with law” (Clause 5, Article 31).

At the same time, “a person charged with a criminal offense shall be promptly tried in an impartial and public manner by a court within a legally established time limit. In case of a closed trial in accordance with law, the verdict must be publicly pronounced” (Clause 2, Article 31).

Though the Code guarantees the most basic human rights, the practical exercise of such rights remains unsatisfactory partly due to unspecific and impractical provisions which need revision in light of the new Constitution.

Strictly controlling the application of measures to limit human rights in criminal proceedings

Procedure-conducting agencies must apply deterrent measures, including arrest, holding in custody, detention, ban on exit or entry, travel from residence or bailout, and other coercive measures such as escort, expedition, distraint or sequestration of assets, blockage of assets to prevent crimes and verify offenses and offenders. However, these measures limit to some extent certain human rights. To avoid the abuse and arbitrary application of these measures, the Code should provide clearer grounds for, the competence to decide on, procedures and time limit for, application of these measures. Meanwhile, procedure-conducting agencies have the duty to regularly check the legality and reasonability of these measures so as to cancel them as soon as they become unnecessary.

The Code should also further improve the mechanism of controlling the application of coercive and deterrent measures by procedure-conducting agencies and persons to ensure acts that limit human rights can only be conducted when really necessary and with approval of the procuracy.

Extending and guaranteeing human rights in criminal proceedings

Under the principle of presumption of innocence, a person charged with a criminal offense should be presumed innocent and, therefore, may still exercise basic human rights and citizens’ rights until proven guilty according to a legally established procedure and the sentence of the court takes legal effect. Even when he is proven guilty and deprived of citizens’ rights, he is still entitled to certain human rights. Therefore, the Code should be revised to extend some basic human rights under certain conditions. For example, Clause 2, Article 88 of the Code, which stipulates “The accused or defendants being women who are pregnant or nursing children aged under thirty six months, being old and feeble people, or suffering from serious diseases and having clear residences will not be detained,” should add some cases in which the accused or defendants are not subject to detention and other deterrent measures (ban on travel from residence, for instance) should be taken against them. These cases should involve those who are caring for their disabled, seriously ill or dying relatives and exclude those who abscond, are arrested under pursuit warrants, relapse into committing another offense or intentionally obstruct investigation, prosecution or trial, infringe upon the national security, or are likely to do so unless they are detained.

The Code also shows respect for and protects the right of detainees, the accused and defendants to their lawful property ownership, which is provided in the new Constitution as everyone’s human right. In Articles 90 and 143, the Code stipulates:

“The agencies that have issued custody decisions or temporary detention warrants shall notify persons in custody or temporary detention of applied property preservation measures,” and

“Search of residences or premises shall be conducted in the presence of the owners or their families’ adult members, representatives of commune, ward or township administrations and neighbors as witnesses.”

However, there should be additional provisions stipulating procedural forms of measures to preserve houses and property, requiring the application of such measures to be stated in case files, and establishing procedures for search in order to guarantee practical exercise of these human rights.

Guaranteeing the right to defense

The right to defense of persons held in custody or detention, persons against whom criminal cases are instituted, who are investigated, prosecuted or tried aims to safeguard their lawful rights from infringement by procedure-conducting agencies.

To conduct self-defense in the spirit of the new Constitution, arrestees, detainees, the accused and defendants need to be informed of reasons for application of deterrent measures, institution of criminal cases, prosecution or trial against them. The Code stipulates:

“A custody decision must clearly state custody reasons and custody expiration date, and one copy thereof must be handed to the persons kept in custody” (Clause 3, Article 86).

However, in case persons held in custody are foreigners or ethnic minority people who cannot speak Vietnamese, are illiterate or visually impaired, it is meaningless to hand custody decisions to them. The Code, therefore, should add the obligation of investigators to read out custody decisions so that persons held in custody can hear or interpreters to translate such decisions into the language which these persons can understand. The Code should also specify in Clause 2, Article 86 how investigators explain rights and obligations of persons kept in custody, especially to those who are uneducated or have no legal knowledge, so as they can exercise their right to self-defense.

To guarantee the right of defendants to have defense counsels, the Code should also add in Clause 2, Article 57 cases in which the court would postpone a hearing because the defense counsel is absent for force majeure reasons, allowing the court to proceed with the hearing if the defense counsel is still absent after the postpone period and the defendant refuses to invite another defense counsel, and cases in which the appointment of a defense counsel for a defendant is compulsory.

The Code, which has no specific provision on the order and procedures for granting certificates to defense counsels, should provide that when a defense counsel fully meets the conditions specified in Clause 1, Article 56 and there is a request of the accused, defendant or his/her lawful representative for selection of a defense counsel, the investigator, procurator or judge assigned to settle the case must immediately grant a defense certificate to the defense counsel.

Guaranteeing the swift and lawful settlement of cases

Perceiving that the prolonged criminal proceedings involving deterrent and coercive measures affect basic human rights, the Constitution affirms for the first time:

“A person charged with a criminal offense shall be promptly tried in an impartial and public manner by a court within a legally established time limit” (Clause 2, Article 31).

This makes it necessary to prescribe in the Code reasonable time limits for conducting criminal proceedings in a swift and effective manner. Such time limits must be long enough for procedure-conducting agencies to detect and handle offenses while safeguarding human rights. Unspecific time limits or absence of time limits for some procedural steps can adversely affect the exercise of human rights. For example, due to the absence of a time limit for a procuracy to consider and approve an investigative agency’s search warrant, such investigative agency often tends to urge the procuracy to immediately approve the warrant without carefully examining the grounds for the search, thus causing the risk of infringing upon human rights. The Code should prescribe stricter time limits for various procedural steps depending on seriousness of criminal cases, facilitating prompt and proper performance of such steps and avoiding dependence on the personal consideration of procedure-conducting persons.

Guaranteeing just convictions

The Code should provide more mechanisms for supervising all activities of procedure-conducting agencies in the course of settling criminal cases, including the mechanism for supervision within each system and from the outside, add provisions on rights and responsibilities of procuracies to better supervise judicial activities and favorable conditions for the presence of defense counsels during interrogation to prevent investigators from using corporal punishment and coercion against arrestees, detainees and the accused.

The Code should also have new provisions facilitating the democratic adversary process, explaining criminal acts in favor of defendants, creating conditions for the accused, defendants and defense counsels to prove innocence, plead for commutation, enjoy equality in collecting, weighing and using evidence, and make arguments and statements at court hearings. Substantial revisions should be made to the provisions of Article 207 of the Code: “1. Trial panel shall determine fully all circumstances of each fact and each offense in the case in a rational inquiring order. 2. When inquiring each person, the presiding judge shall put questions first, then procurators, defense counsels and defense counsels of interests of involved persons,” as they can lead to the court’s prejudgment that defendants are guilty and make questioning biased against defendants while limiting chances for defendants and defense counsels to argue against allegations and prove their innocence.-