Đặng Ngọc Dinh, Đặng Hoàng Giang, Edmund J. Malesky,

Paul Schuler, Sarah Dix and Đỗ Thanh Huyền[1]

Introduction

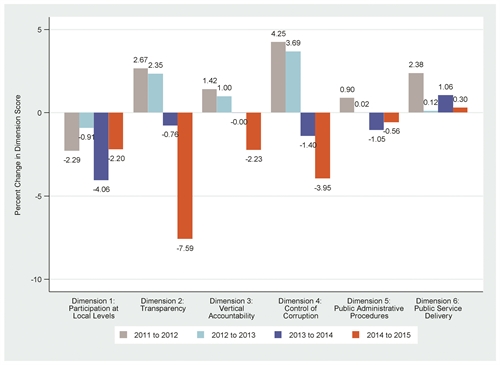

Findings from the 2015 Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI), which assesses citizen experiences with national and sub-national government performance in governance, public administration and public service delivery, show declines at the national level in five out of the six governance dimensions the survey measures. Specifically, there was a substantial drop in scores in the transparency and control of corruption dimensions, and a significant decline in local level participation and vertical accountability. There was also a slight decrease in the performance of public administrative procedures in comparison to previous years. On a positive note, public service delivery scores continued to increase modestly.

The Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI)[2] is a policy monitoring tool that reliably assesses citizen experiences and satisfaction with government performance at the national and sub-national levels. PAPI aims to improve the performance of local authorities to meet their citizens’ needs in two ways.

First, it creates constructive competition and promotes learning among local authorities. Second, it enables citizens to benchmark their local government’s performance and advocate for improvement. It does this by offering a unique opportunity for a nationally and provincially representative sample of the population to provide feedback to government, as well as an opportunity for government to hear citizens’ voices. In doing so, PAPI is helping to build a performance culture within national and provincial governments to support better policymaking, management of public resources and public service delivery.

The past five years of annual nationwide PAPI surveys coincide with the 2011-2015 government term, providing both a retrospective evaluation of the Government’s accomplishments and a benchmark to gauge performance during the next term. In addition to six performance indices - which are based on a core set of questions every year - the 2015 PAPI survey includes new questions on a range of topics. Responses from 13,955 citizens in 2015 offer policymakers a look at what issues citizens care most about as well as policy measures that can address citizens’ rising expectations.

Declines in Governance Performance

Looking across the six dimensions that PAPI measures, the 2015 results reveal a dip in performance in the four measures of governance. Most noticeably, the transparency dimension declined sharply, falling more than 7 percent in 2015 compared to previous years (see Figure 1). This is partly because of less public awareness of poverty lists and, among those who have seen the lists, less confidence in their accuracy as compared to previous years. Also, fewer citizens were aware of the commune budget and expenditure information and did not feel confident about the accuracy of this information. In addition, there was less publicity of local land-use plans and land price frames, and citizens had fewer opportunities to comment on land-use plans. The issue of compensation for land seizure remains problematic, with ethnic minorities proving to be less satisfied with compensation levels than ethnic Kinh. (See Figure 1)

|

|

The updated PAPI findings continue to show the endemic nature of corruption in Vietnam. Overall, the control of corruption dimension fell by 3 percent in 2015. This is because in a number of indicators, such as bribes in primary education and bribes for land use rights certificates, scores are worse than before. Citizens across the country consider nepotism and bribery in the public sector to be prevalent, and they sense a lack of willingness to fight corruption on the part of the local government and citizens themselves. Results from a new question on the issues of greatest concern to citizens show that corruption was the third most concerning issue, after personal economic issues (such as poverty, employment and income) and roads (which are essential for transport and commerce).

Another problematic area is the decline in citizen participation in political life and policymaking. The indicator on opportunities for participation has continued to fall since 2011. Much of this decline is likely due to the fact that the latest round of National Assembly and People’s Council elections was four years ago, in 2011. With elections coming up in 2016, this indicator will be one to watch in the next PAPI report. On participation in law-making, only 13 of respondents across the country reported being asked to participate in the drafting of ordinances and laws. Participants were much more likely to be men, party members, members of mass organizations or have higher levels of education.

Based on a review of the national results, the following recommendations are made for policy interventions and actions in 2016 and beyond:

1. While the 2013 Land Law may have tightened procedures, more work needs to be done to ensure that land-use plans and land price frames are publicized and that compensations for land seizures are more fair for land users of different demographic backgrounds. In particular, a closer examination is necessary of why ethnic minorities report receiving lower levels of compensation or no compensation at all for land seized.

2. Vietnam must step up its efforts to curb corruption. Despite the high-level attention paid to the issue, the 2015 PAPI results show that corruption is pervasive. Effective anti-corruption action plans are needed, in addition to greater willingness of public officials and civil servants to curb corruption at all levels of government.

3. To increase citizen participation all voters, especially women, should be encouraged to vote directly in the 2016 elections. Also, the rule of ‘one person, one vote’ needs to be observed by both electoral committees and voters.

Civic Knowledge, Access to Information and Political Participation

As Vietnam prepares for its 2016 National Assembly election, the 2015 PAPI Report examines in detail the factors that determine citizen participation in voting and in contributing opinions on laws. As different citizens have different interests, views and experiences, encouraging participation from a demographically representative group of citizens is essential to ensure that the feedback the Government hears is representative of the country.

Findings from the analysis show that factors such as gender, education and mass organization membership impact citizen participation in Vietnam through political knowledge and access to information. With regard to elections, the PAPI survey shows that gender, ethnicity, mass organization membership and education directly impact voter participation. Women, ethnic minorities, those who are less educated and those who are not members of mass organizations are less likely to vote. Political knowledge and access to information also play a role, with politically uninformed citizens being less likely to participate in elections.

However, in terms of participation in law-making the picture is different. As mentioned earlier, participation in local government discussions on laws or ordinances is low, at only 13 percent. Party membership is by far the largest predictor of whether or not an individual is asked to participate (see Table 1). A closer look at the survey results suggests that many more citizens are willing and potentially interested in contributing, but are currently disengaged from the process.(See Table 1)

| Table 1: Patterns of Participation in 2015 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The challenge of how to increase political participation is clearly a multifaceted problem. The PAPI 2015 findings suggest the following:

1. Mobilizing more women and minorities to vote in elections and increasing their awareness of and interest in politics are important. The less educated and those who are not members of mass organizations should also be encouraged to vote. In general, greater political knowledge and access to information have the potential to increase the number of people who vote and to make voting more representative of Vietnam as a whole.

2. To increase citizen participation in policymaking, greater efforts could be made to include a broader representation of society. Including citizens outside local political networks leads to better decisions because it brings new expertise to the table and helps tailor local initiatives more closely to the needs of citizens.

3. There is the potential for a virtuous circle to develop. Convincing underrepresented citizens that their voice matters in policy creation, implementation and monitoring gives them a greater stake in the process and outcomes, which in turn encourages them to seek out more information and education on the issues. As a result, policy decisions will be improved because of the higher quality of information available to decision makers. From the citizen perspective, greater participation enhances legitimacy and ultimately leads to greater compliance with the law.

Provincial Performance in 2015 and a Five-Year Comparison

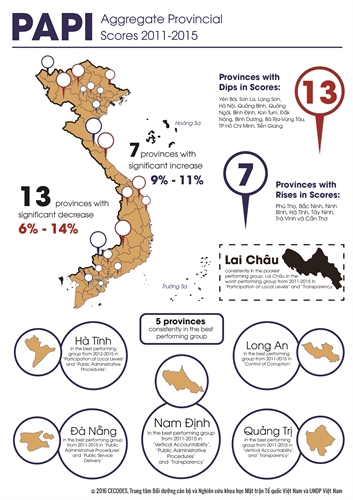

Not only does PAPI identify good and poor performers, it also enables good practices at the provincial level to be shared with provinces with similar socio-economic and geographic characteristics. Overall, the better performing provinces in 2015 are found in the north-eastern, central and south-eastern regions of the country. The poorest performing provinces are found along the northern border and in the south-central and Central Highland regions. These geographic patterns have been consistent over time since 2011.

The efforts of local governments in Nam Dinh, Ha Tinh, Quang Tri, Da Nang and Long An, who have all been in the top performing group in overall provincial performance for the last five years, should be acknowledged (see Infograph 1). Thai Binh has been in the top performing group since 2012. At the other end, Lai Chau has been in the poorest performing group since 2011 and Ninh Thuan has been rated poorly since 2012. Seven provinces (Bac Ninh, Can Tho, Tra Vinh, Ninh Binh, Tay Ninh, Phu Tho and Ha Tinh) have improved significantly since 2011, with an increase in their aggregate unweighted scores between 9 percent and 11 percent. Meanwhile, 13 provinces have seen significant drops in their scores over the course of five years, with Ba Ria-Vung Tau and Binh Duong dropping the most, as compared to their 2011 baselines.

| Infograph 1 |

|

Participation at Local Levels: Practice Citizens’ Constitutional Right

Participation in political, social and economic life is a Vietnamese citizen’s constitutional right, enshrined in the country’s Grassroots Democracy Ordinance and other legislation. As such, citizen participation is a fundamental aspect of governance in Vietnam. PAPI measures citizens’ knowledge of their participation rights and how they exercise them.

Participation at the local level remains limited in the aspects PAPI measures, with scores in the three sub-dimensions (knowledge of the right to participate, opportunities to participate and quality of village head elections) declining compared to the 2011 baselines. Village head elections remain largely symbolic, with widespread practices such as having just one candidate and candidates being suggested by the authorities in place. The ‘voluntary contribution’ sub-dimension score was more positive, as citizen participation in starting a local infrastructure project was higher in 2015.

Most of the best performing provinces in 2015 are in the north-eastern and central regions. This pattern has existed since 2011 and seems to have become even stronger in the north-central part of the country during the past five years. Thai Binh and Ha Tinh have been in the best performing group for four years in a row. Overall, there has been a significant downward trend in citizen participation in two thirds of the 63 provinces between 2011 and 2015. The largest drops are in Lang Son, Son La, Lai Chau and Ba Ria-Vung Tau, where provincial dimensional scores dropped by at least 25% over five years. The north-western province of Lai Chau has been in the poorest performing group since 2011.

Improving citizen participation in local governance would not require a large financial investment from the state budget. It, however, needs strong commitment from relevant state agencies and local governments to putting the Grassroots Democracy Ordinance into force and to engaging citizens in political life and policymaking. The upcoming 2016 National Assembly and People’s Council elections also offer an opportunity to ensure ‘one person, one vote’ and greater participation in voting.

Transparency: Observe Citizens’ Rights to Know

PAPI measures citizens’ “rights to know” about state policies that affect their everyday lives and livelihoods. Transparency here is based on sub-indicators in three areas: transparency of poverty lists, commune budgets and expenditures, and local land-use planning and pricing. Information relating to these is required by the Grassroots Democracy Ordinance and recent legislation to be made publicly available so citizens across the country can “know, discuss, do and verify”.

As indicated earlier, transparency declined sharply due to the downturn in almost every measure in 2015 in most provinces. Among the 63 provinces, 11 saw improvements of more than 5 percent in 2015 compared to 2011, while 17 saw a significant decrease over time. More northern and central provinces are found in the group of better performers than southern ones. In a number of provinces, there is consistent performance over time. For instance, Nam Dinh and Quang Tri have been in the best performing group for five consecutive years. Meanwhile, Lai Chau, Bac Lieu and Kien Giang have been in the poorest performing group since 2011.

To improve transparency, it is important for local governments to find and adapt different means of disclosing trustworthy information to citizens with different demographic backgrounds. This can be done through government portals at provincial and district levels, although as PAPI findings show only about 25 percent of respondents have Internet at home and very few (about 7 percent) go onto the Internet to search for information about land price frames. For this reason, in rural and remote areas notice boards at the commune level or loudspeakers at the village level would help disseminate information.

Vertical Accountability: Facilitate Citizens’ Rights to Discuss and Verify

This dimension measures key ‘vertical accountability’ aspects, including interactions with local authorities and the coverage and effectiveness of People’s Inspection Boards (PIBs) and Community Investment Supervision Boards (CISBs). These mechanisms help to make local governments and public officials accountable to their citizens.

Overall, in most provinces vertical accountability has slightly decreased as compared to previous years. The largest drops in 2015 relate to the presence and effectiveness of PIBs and CISBs, which are set up to represent citizens on oversight at the grassroots level. For instance, only 30 percent of citizens surveyed are aware of a PIB in their locality and only 19 percent of citizens are aware of CISBs in their communities. Despite higher frequencies nationwide of citizen-government interactions at the grassroots level, the effectiveness of such interactions was lower in 2015.

Most of the top and high-average performers in this dimension for the 2011-2015 period are north-central provinces. Notably, Da Nang, Quang Binh, Ha Tinh and Quang Tri have been rated highly on citizen interactions with local authorities. Bac Ninh’s dimensional score rose 23 percent in five years, while Ha Nam’s dropped 15 percent. A promising new trend is seen in the north-western and Mekong south-western regions, with more provinces here emerging in the top group.

In light of these findings, it is recommended local authorities interact more with citizens through regular and ad-hoc direct meetings as chartered in their provincial decisions on meetings with citizens and constituents. The Law on Citizen Reception, effective from July 2014, provides the legal framework for better government-citizen interactions. Another recommendation is that the Vietnam Fatherland Front, mass organizations and civil society should play a key role in reviewing the interaction mechanisms and finding ways to improve their effectiveness. To ensure more effective PIBs and CISBs these should be combined, better equipped with the appropriate skills, better resourced and actively engaged with citizens and civil society organizations.

Control of Corruption in the Public Sector: Incentivize Citizen Reporting

PAPI measures four aspects of citizen experiences with local government performance in controlling corruption: limits on public sector corruption, limits on corruption in public service delivery, equity in state employment and willingness to fight corruption. It also measures the tolerance of corruption practices by citizens.

As mentioned earlier, efforts to control corruption at the provincial level have had limited effects. That said, more than a third of provinces have improved their performance by at least 5 percent since 2011. Cao Bang improved by 33 percent and Tra Vinh improved by an impressive 47 percent. Tra Vinh was also the best performing province in 2015 thanks to the highest scores in the ‘limits on corruption in service delivery’ and ‘equity in state employment’ sub-dimensions. Nam Dinh was the best performer in terms of willingness to fight corruption from both local authorities and local citizens.

Looking across the country, central and southern provinces tend to do better on corruption control than northern ones. In 2015, among the top 16 best performers, 11 are southern provinces and four are from the central region. Long An and Soc Trang have been in the best performing group for five years in a row. However, the greatest drop was witnessed in the southern province of Binh Duong, with its score falling by more than 30 percent compared to 2011. In the same period, Hanoi has consistently remained in the poorest performing group.

Poorer performing provinces can learn from better performing ones about their experiences in ensuring greater equity in state employment and reducing bribery in public services. They can also learn important lessons on how to curb the abuse of public officials’ power to divert state funds and obtain informal payments in the provision of public administrative services and in state employment. Ensuring positive change also requires greater willingness by citizens to denounce corrupt acts. This kind of reporting can be facilitated by the participation of both non-governmental actors and the media, who can serve as channels for citizens to report corruption.

Public Administrative Procedures: Continue Reforms in Land Procedures

This dimension examines the quality of public administrative services in areas important to citizens, including certification services and application procedures for land use rights certificates, construction permits and personal documents. Citizens are asked about their experiences with using these public administrative services. The criteria include the transparency of procedures and fees, the competence and behavior of civil servants, paperwork loads, deadlines and overall satisfaction with the public administrative services.

The performance of provinces has remained relatively stable over time in this area. Moreover, as compared to other dimensions measured by PAPI, this dimension has a smaller gap between the best (Bac Ninh) and the poorest (Quang Ngai) performing provinces. Although there is little difference between the groups, Da Nang, Quang Binh, Ha Tinh and Nam Dinh have been in the best performing group since 2011, while only Soc Trang has been in the poorest performing group for five consecutive years. Over the five-year period, just six provinces made significant improvements, with the most change happening in Can Tho whose dimensional score increased by about 16% compared to the 2011 benchmark.

Among the four public administrative services measured, the quality of the administrative service to obtain land use rights certificates has since 2011 been scored the lowest and has even declined significantly compared with previous years. Although the quality of certification services also declined slightly, these services still performed much better than services for construction permits and land use rights certificates. On the other hand, the application procedures for personal documents handled by commune-level People’s Committees received the highest user satisfaction, with 96 percent of those who used the service reporting they had a good experience with it. However, commune-level one-stop shops for personal documents saw a slightly lower level of user satisfaction in 2015 compared to previous years.

It is clear from the findings that transparency in application fees and meeting deadlines are key attributes of higher user satisfaction with administrative services in general. Measures to increase citizen satisfaction with public administrative services therefore include relevant local government agencies displaying fees and charges at one-stop shops and notifying applicants of changes in deadlines. For commune-level administrative services, it is essential to improve the competence of commune officials handling the procedures for applicants.

For land title related services, it is important for provincial departments of natural resources and environment in all provinces to strengthen and supervise the functioning of district affiliates by almost every criterion in order to increase user satisfaction. By providing clear information about required procedures, increasing the transparency of fees and charges, simplifying paperwork requirements, providing a clear deadline of when final results are returned and performing the service within the promised deadline, this service will improve. All these suggestions are also covered in the 2013 Land Law and its by-laws, which relevant local government agencies have to implement.

Quality of Public Service Delivery: Ensure Coverage for All

The quality of public service delivery is examined in PAPI through four key public services: public health care, public primary education, basic infrastructure and residential law and order. Citizens are asked about their experiences with the accessibility, quality and availability of basic public services in their communes, districts and provinces.

Findings from the 2015 PAPI survey confirm the stable trend in provincial performance in public service delivery over the past five years. The gap between the best performing province (Vinh Long) and the poorest performing (Dak Nong) is the narrowest among the six dimensions. This shows a convergence of provinces toward a relatively similar level. Among the public services assessed, basic infrastructure (electricity, roads, clean water and garbage collection) improved slightly, while public primary education and law and order remained consistent and public health care experienced a decline in user satisfaction. In health care, there was also a greater gap between the best and poorest performing provinces in terms of the quality of public district hospitals.

Over the past five years, better service delivery performers have tended to be concentrated in the south. The five provinces of Vinh Long, Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh City, Kien Giang and Ba Ria-Vung Tau have been in the best performing group since 2011. Meanwhile, Binh Phuoc and Dak Nong have been in the poorest performing group for five consecutive years. On the whole, none of the provinces have fallen behind dramatically over the past five years. In the same period, there has been some improvement in 28 provinces. The most impressive improvers are Ha Giang, Hung Yen and Ninh Binh, with increases of more than 15 percent compared with their 2011 baselines.

It is worth highlighting the findings on basic infrastructure provided by local governments since, as mentioned above, this area (in particular roads) was cited as a top concern among respondents. The findings show that mountainous provinces need to overcome unfavorable conditions in order to catch up with lowland provinces. Across the country, about 97 percent of households had access to electricity in 2015. However, in the north-western province of Lai Chau only 58 percent reported access to national gridlines. The northern mountainous province of Ha Giang was at the bottom of the list on quality of roads. In the Central Highlands province of Gia Lai only 2 percent have access to clean water, while in the central coastal city of Da Nang almost every household has access to clean water.

Although citizens assess that the provision of public services and basic infrastructure is stable, it is important for provinces to continue improving these services. Better public services, in particular health and education, will contribute to better human resources that can foster innovation and creativity. Moreover, better infrastructure and law and order will help boost productivity and efficiency. Poorer provinces, especially those in the northwest and Central Highlands regions, need to invest more in basic public services, such as public hospitals, schools, roads and basic infrastructure, so that more equitable opportunities are created and their citizens are able to catch up with citizens in other provinces. This will help unleash local potential and lead to sustainable development.

Final Remarks

Over the years, PAPI has been used by a wide range of stakeholders both inside and outside of Vietnam for government performance assessment and policy review. For example, a growing number of provincial government authorities have responded to PAPI’s findings. To date, over 26 provinces have used PAPI in their action plans, directives and resolutions to improve their implementation of general governance measures, administrative procedures and service delivery. More than 40 provinces have hosted workshops to look more closely at citizen feedback of their performance. In addition, PAPI data and information have played an important role in an emerging number of policy documents from think tanks, international development partners and universities.

The impact PAPI is having is testament to how data and evidence is helping improve public policies in Vietnam. An important message for policymakers and practitioners is that PAPI scores should be read as an opportunity to assess performance across a wide range of issues, and not as a critique or call to improve a particular score. Therefore, for poorer performing provinces to catch up with better performing ones, it is important for local governments to systematically look at the specific indicators that show where they have performed well and where they need to improve. By creating action plans to respond to gaps, and implementing them, local governments are able to increase citizens’ satisfaction. It is also important to create equity in access to good governance and public administration, especially for women, ethnic minorities, young people and citizens who are not party members. Together, these actions will help Vietnam harness its human potential, benefit the country’s development and support the fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, which Vietnam has committed to.-