Erwin Schweisshelm[1] and Truong-Minh Vu[2]

Following the launch of a transition process from a planned to a market economy in 1986, the textile and clothing industry was one of the first industrial sectors to establish itself and start growing. It is a trend that has continued until today, and one that was given an extra boost following accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007. The textile and clothing industry receives a great deal of support from the Vietnamese government: ambitious plans were drawn up to develop the sector further.

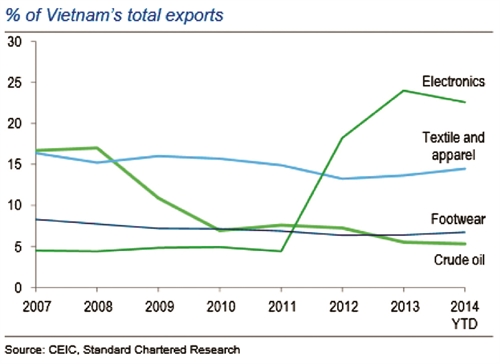

Although the figures vary, it is estimated that 2.5 million people are employed in this sector, with most of the workers being women.[3] The Vietnamese Textile and Apparel Association (VITAS) recently estimated that the sector comprises a total of more than 5,000 companies, of which approximately 4,500 are sewing rooms, 500 weaving mills and 100 spinning mills. Currently, textile and apparel account for 13.6 percent of Vietnam’s total export value[4]; accordingly the sector ranks second only to electronic products in terms of net proceeds.[5]

Table: Export industries in Vietnam

|

The share of Vietnam in the global apparel export market was 3.7 percent in 2013.[1] VITAS forecasts a total export volume of approximately USD 24 billion[2], i.e., an increase of about 19 percent compared with 2013. (Growth rates in China and India were substantially lower.) In 2015, the aim was to increase volumes by a further 20 percent. This was not unrealistic given the drop in oil prices and the drop in costs for fiber materials. And VITAS predicts that the textile exports will grow at an annual average rate of 11.5 percent until 2020.

Big but not a strong

The global supply chain in the production of Ready-Made Garments (RMG) is complex, diversified and global. It is typically divided into five basic stages: 1) Supply of raw materials, including natural cotton, thread, etc; 2) Production of intermediate goods; products of this stage are fibers, fabrics provided by weaving, knitting and dyeing companies; 3) Design and manufacture of finished products by garment companies; 4) Export by commercial intermediaries; and 5) Marketing and distribution[3].

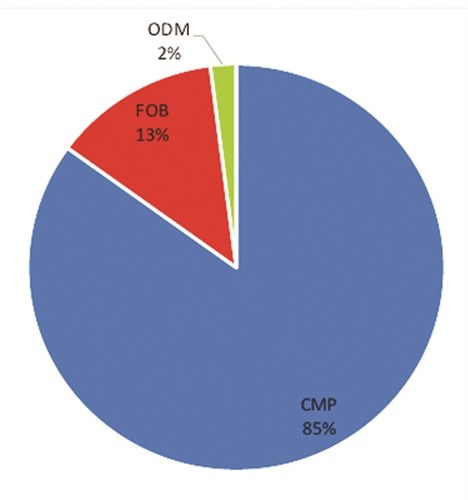

Accordingly, the highest added value appeared to be in the design and marketing and distribution stage. Meanwhile, the added value will decrease and reach the lowest level in the labor-intensive Cut-Make-Pack (CMP) process. This is the stage where production in Vietnam is presently mainly located. 85 percent of Vietnamese enterprises manufacture in the form of CMT, incontinence output and input materials, low-added value. Only the remaining stages reach higher stages of value adding like Free on Board (FOB) on a lower level (inputs and supplies from sources designated by the lead brands) or original design manufacturing (ODM) which includes elements of design. (See Figure)

Figure: Vietnam in the global garment and textile value chain (2015)

|

Source: Lefaso (2015)

At present the Vietnamese share in global RMG exports is still small. China remains the unchallenged market leader with 39 percent (2013). Nonetheless, growth in the Vietnamese textile and clothing industry has proven very dynamic over the course of the country’s economic opening, underway since the 1990s. According to VITAS, Vietnam’s exports are sent to 50 countries and territories. 52.8 percent goes to the US (Bangladesh: 24.1 percent), while 17 percent is exported to EU countries[1] (Bangladesh: 59.7 percent) followed by Japan and Korea.

For the next decade the TTP will be especially important for Vietnam. Peter Petri’s seminal study “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment,” is being widely discussed in Vietnam. This study argues that Vietnam would be the largest beneficiary of the TPP. It is cited as the key reason Vietnam joined the negotiations, and has bolstered a growing number of pro-TPP voices among the public. According to another estimating research of the World Bank released in 2016, Vietnam is in a position of getting more gains than losses from TPP. In economic terms, Vietnam will arguably be one of the biggest beneficiaries from TPP. Vietnam’s export in apparel and footwear will increase by about 50 percent.

The effect of TTP can be exemplified by the ready-made garments sector in Vietnam. The TPP will incorporate Vietnam in this sector into the global value-added chain to an even greater extent than has hitherto been the case. The TPP member countries represent 40 percent of global GDP and 30 percent of world trade volume. Especially the textile sector of Vietnam would strongly benefit from creation of the TPP and overtake Bangladesh in a few years in terms of market share in global exports. This will depend on how the “rules of origin requirements” will be applied in the TPP for Vietnamese apparel exports to the US. According to a recent report of the World Bank, if the TPP takes effect Vietnam’s garment and textile sector could grow 41 percent by 2020. This is especially true for the US market where tariffs will come down to zero from the current 17.5 percent and export volume may reach USD 55 billion in 2025.[2]

These very optimistic expectations contradict with persistent problems in the Vietnamese textile and clothing industry. On the one hand the industry complains about rising labor costs, whilst on the other hand there is the persistent dependency on imported raw materials and pre-products for garments. One of the conditions attached to TTP is that the intermediate products for textiles, which are to be exported in the TTP area on preferential terms, must also come from a TPP member country. This is called yarn forward rule or triple transformation. Yet China and South Korea alone (both no TPP countries) account for 54 percent of all imports, and are accordingly still Vietnam’s main source for intermediate products. Imports from other countries might be substantially more expensive than from China or South Korea. Although the US has insisted on the yarn forward rule to promote its vanishing domestic textiles industry.

If Vietnam could quickly meet the rules of origin requirements, the market share in the global clothing industry could increase from approximately 4% at present to 11 percent in 2024. Vietnam would then rank second behind China, whose share would drop. Bangladesh’s market share would only rise from 5 percent to 7 percent. The losers would be the Central American producers, who at present primarily serve the American market[3] within the NAFTA framework. If there will be less flexibility on sourcing for Vietnam (triple transformation), in 2024 Vietnam and Bangladesh would each have a market share of 8%, according to this study. Also countries like Cambodia, Myanmar, Indonesia and Pakistan will lose market share to Vietnam in RMG trade.

Many investors see Vietnam as an alternative. This is also due to increasing labor costs in China and the tragic accidents in Bangladesh. But especially the upcoming Free Trade Agreements enforces the trend of relocating textile and garment production from China to neighboring countries, especially Vietnam. The Chinese government does encourage such investments of Chinese companies overseas, under a program called “Going Out”. According to the China National Textile and Apparel Council (CNTAC), Vietnam is the first choice for overseas investment, because of its potential savings on cotton material, labor cost, logistic cost and duty-free barriers, and Vietnam is also a potential consumer market.

China is still the world leader in garment exports with a value of USD 170 billion in 2015, but Vietnam is catching up. The National Bureau of Statistics now says the mainland’s average manufacturing wage in 2014 (the latest data available) was the equivalent of USD 8,300 a year. The comparable figure for Vietnam is about USD 3,000 and for Bangladesh about USD 1,000.[4]

The question of productivity

Despite this promising development, VITAS emphasizes that there are persistent problems in the Vietnamese textile and clothing industry. On the one hand are rising labor costs, whilst on the other there is the persistent dependency on imported raw materials, especially from China. Notwithstanding the above, the domestic industry has invested heavily, and significant progress has been made. The degree of localization has been increased in a relatively short period of time, including localization of cotton fabrics made of natural or synthetic fibers. Furthermore, the focus of production has successfully been shifted to quality products over the last years. Design, product development and marketing are also set to be provided by domestic firms at an increasing rate.

The Vietnam Textile and Garment Corporation (VINATEX) wants to raise the local content of its products to 60 percent as of 2018. In October 2014, Japanese investment group Itochu Corporation bought approximately 5% of the publicly offered shares. VINATEX plans on investing approximately USD 440 million in production sites, dyeing mills, fiber production and infrastructure. All the same, when compared to foreign competitors, VINATEX is losing ground given the poor investment potential of its subsidiaries[5]. Another important player is the aforementioned inter-branch organization, VITAS. It has more than 700 members, including foreign companies mainly from Korea, Taiwan and Japan.

Helping local enterprises enlarge local content and move up the RMG value chain should be a crucial element of industrial policy of the Vietnamese government. In a sign that the country has felt which way the wind is blowing, a number of Vietnamese companies are already starting up, or expanding, their own fiber manufacturing operations in order not to be left behind when the TPP is finally implemented. Key companies include the Century Synthetic Fiber Corporation (CSFC), Thanh Cong Joint Stock Co (TCM), and VINATEX.

But also foreign investors are flocking into the establishment of spinning, knitting and dyeing factories in Vietnam, among others the Japanese Itochu Corporation, Far Eastern New Century Corporation from Taiwan or Crystal Group from Hongkong, to name just a few. Additionally, in a further bid to enhance the competitiveness of the country’s fiber manufacturing industry, Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade has proposed levying a two percent import tax on polyester staple fiber (PSF). Currently PSF imports are not subject to tax. Also numerous Japanese fabric companies increase their relocation of production to Vietnam, assuming that Vietnam can also be used as a gateway to ASEAN markets because of its strategic location.[6]

The big fear of the Vietnamese enterprises is that they may lose out to the foreign investors because they have more financial capabilities and experience. Compared to other exporters of apparel in the region though, there is limited machinery, little equipment and technology, and the productivity of workers is still relatively low. This disadvantage can no longer be offset by an abundant supply of labor. Mergers and acquisitions with foreign and local companies in the Vietnamese textile and garment industry are on the rise.

In a way the upcoming free trade agreements can either accelerate the race to the bottom and drive Vietnam in the trap of FDI-driven, export-oriented, low-wage manufacturing with little value-adding or become a driver for productivity growth and scaling up not only in the textiles and garment industry. The government is attempting to solve this problem by investing in training and the service infrastructure but a comprehensive master plan for the industry is yet to be seen.-