The 2020 Vietnam Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) Report,[1] released on April 14, 2021, assesses citizen experiences with national and local government performance in governance, public administration, and public service delivery at the provincial level. Apart from national and provincial findings on governance and public administration performance from permanent and temporary residents[2], the PAPI Report had a special section to look into drivers of migration inside and out of Vietnam. This article introduces findings from this thematic discussion in the Report.[3]

Center for Community Support and Development Studies, the Vietnam Fatherland Front Center for Research and Training, and United Nations Development Program

Introduction

Drivers for migration within and out of Vietnam have been previously studied because of the dynamics, costs and benefits of migration. This article examines motivations for international and internal migration from the 2020 PAPI survey with 14,732 respondents who were face-to-face interviewed in the second half of 2020. Besides questions regarding local governments’ performance in governance and public administration, the respondents were queried about what would make them leave their provinces of permanent residents and where would they choose to move to internationally and domestically.

The reasons for the PAPI research team to look deeper into the drivers of migration are two-fold. First, as a result of the tragic incident in October 2019, where 39 Vietnamese migrants died in a lorry while trying to reach the United Kingdom,[4] there were also extensive discussions about migration in 2020. Many commentaries suggested that large numbers of Vietnamese citizens, particularly from poorer regions of the country, were likely to put themselves at a great risk to migrate. Second, the impact of climate change on migration was also raised in 2020. This became a public concern when maps showing the possible effects of climate change in Vietnam were widely reported in the media.[5] The maps showed the possibility that vast swathes of Vietnam, particularly in the Mekong Delta region, could be flooded by 2050. Such catastrophic flooding raises concerns about a wave of internal “climate refugees” in Vietnam, which could place great strain on the country’s urban areas.

Destinations and reasons for migration

To understand motivations for migration, it is important to know who want to move out of their localities permanently and where to. The 2020 PAPI survey includes a question about the likelihood that a respondent will move permanently outside her/his province in the future on a scale of one to 10. The survey also asks the preferred destination the respondent desires to move to.

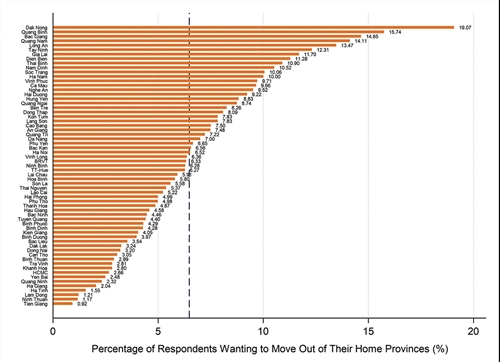

According to the survey, only about 6.5 percent of the population expressed any desire to move permanently out of their province. Figure 1 shows the breakdown by province. As can be seen, provinces in the Central Highlands and Central regions of the country have the highest percentage of respondents expressing they want to move. Dak Nong, in particular, has 19 percent of respondents wanting to move out of the province. By contrast, consistent with findings from other countries,[6] those in large urban areas express less desire to move. Fewer residents from Can Tho and Ho Chi Minh City, for example, expressed a desire to leave their province.

|

|

To assess the provincial determinants of a resident’s desire to move, statistical analyses show that governance did not play a major role. There was no relationship between provinces that are better governed and a resident’s desire to move. This may suggest that economic factors play a more important role.

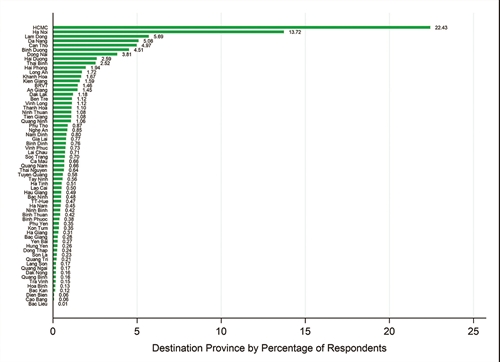

Figure 2 shows the preferred destination within Vietnam for migrants. The two most popular destinations are Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, with the latter attracting 22 percent of respondents wanting to move, doubling the amount of those who want to move to Hanoi. Lam Dong is the third most popular destination, with 5.6 percent of those responding that they would move to another province choosing Lam Dong as their destination. Da Nang and Can Tho were the fourth and fifth most popular destinations at about 5 percent each. Closely following were Binh Duong and Dong Nai, peri-urban industrial areas. This clearly shows that as in other countries, most migrants prefer to move to urban or peri-urban areas within the country. The one, perhaps, surprising province is Lam Dong, but this is likely a popular province because of Da Lat’s role as an economic hub for those in the Central Highlands.

|

|

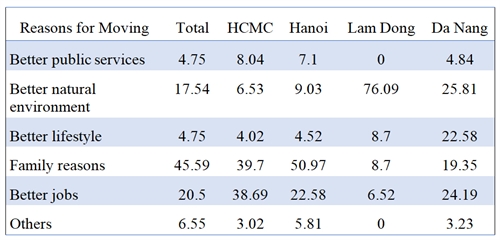

Table 1, which shows the motivation for moving, provides an explanation for the inclusion of some of the surprising provinces. Across the country, the biggest driver of a desire to move is family reasons. Nearly half of those expressing their expectation to migrate suggested that a family reunion was the primary reason. This is followed by a desire for a better job and a better natural environment. A deeper look at the top four provinces (Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, Da Nang and Lam Dong) reveals that those desiring to move to these provinces differ in their reasons. Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi and Da Nang are preferred destinations for family reasons and job opportunities, while Lam Dong’s attraction is its natural environment.

Table 1: Reasons for wanting to move, 2020 (%)

|

The findings suggest that better jobs and family reunion are an important draw, with urban and peri-urban areas providing the greatest magnet for migrants. At the same time, there is evidence that environmental factors can be a draw.

With regard to international migration, very few want to move internationally. Less than 1 percent of respondents said they would move outside Vietnam if they left their province. For those who want to move to another country, the top three desired destinations are the USA, Japan and Australia. This confirms other research findings suggesting that international migration is largely not on citizens’ minds, unless approached by a broker.[7]

Drivers of migration

What types of people are more likely to move? How do poverty, gender, age and other factors drive a propensity to move? Existing research suggests that a person’s propensity to move out of their current home province is driven by factors such as:

- Gender: Social norms may make it more acceptable for men to move.

- Age: Younger people may be more willing to take risks.

- Risk aversion: Those less willing to take risks may be less willing to move.

- Income: Lower income could increase a desire to move, but at the same time decrease the ability to move.

- Education: Education could lead to a greater desire to move to maximize income from higher education levels. Education can also increase awareness of opportunities elsewhere.

- Public services: Citizens may prefer to move of a desire for better public services.

- Family obligations: Having children may constrain the ability to move.

- Social networks: Having family outside the province could act as an information source, a network to attract migrants and help provide access to public services.

- Area: Those in rural areas may be more likely to move to urban areas for economic opportunities.

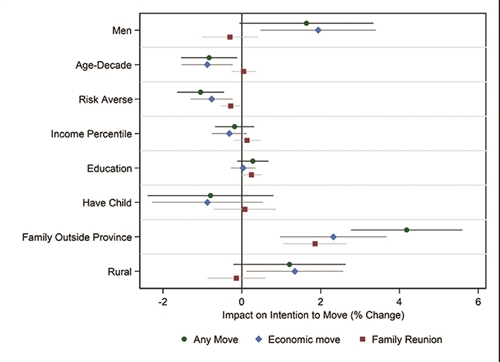

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the factors listed above and the desire to move in general and for job and family reasons. The colored points are estimated effects of a one-unit increase in that factor on the willingness to move. For instance, men are nearly 2 percent more likely than women to want to move for any reason. Men are also more likely to move for better jobs than women, with men about 2 percent more likely than women to express this desire. However, there is no difference between men and women in their wish to move for family reasons. In terms of age, younger respondents are more interested in migrating. Each decade increase in age decreases the intention to move by about 1 percent. Interestingly, education and income play a smaller role. There is only a small effect of an increase in one’s personal income decreasing the desire to move for job opportunities. The effect of increasing one’s income by 20 percentage points results in less than a 1 percent decrease in the willingness to move. Similar small effects are found for education.

|

|

Other factors that matter are risk aversion[8] and living areas. Those who are risk averse are less likely to want to move, particularly for better jobs. An increase in risk aversion by one standard deviation decreases one’s propensity to move by about 1 percent. Rural respondents are also more than 1 percent more willing to move. However, the strongest factor in determining willingness to move is having family outside the province. Those with family outside the province are 4 percent more likely to express their desire to move compared to those without family outside the province.

This analysis shows that younger, male Vietnamese residents - poor and wealthy alike - are the most willing to move. In particular, those who are willing to accept risks and who live in rural areas are more likely to move to urban and peri-urban areas. Having a family outside the province further increases the readiness to move, emphasizing the importance of a family network. Despite this, the analysis shows that unless approached by e.g., a broker, most Vietnamese residents do not consider international migration a viable option. Finally, while one’s individual income level is not the strongest determinant of the motivation to move, the wealth of one’s province of origin is.

Possible impact of climate change on migration

This section assesses the potential impact of climate change on population movements within the country. There is growing concern that climate change is going to lead to an explosion of international migration, or “climate refugees.” This became a particularly pertinent issue in Vietnam last year when several media outlets published articles citing a report from Climate Central showing how hard Vietnam would be hit by climate change.[9] The report estimates about 31 million people in Vietnam - almost a third of the population - could be impacted by rising sea levels. This has already led to the migration of some in the Mekong Delta and could potentially lead to more “climate refugees” in the future.[10]

To assess the potential impact of climate change - and information about climate change - on the desire to migrate, the 2020 PAPI survey included an experiment that looked at how exposure to information about climate risks, such as a sea level rise, impacted citizens’ desire to move. The survey provided a subset of respondents with different levels of information about climate risks in Vietnam by 2050. The goal of the experiment was to see how information about the possibility of a sea level rise, particularly in regions most likely to be impacted by the rise, would impact respondents’ desire to move.

A random subset of PAPI respondents received five different versions of the survey question on the desire to migrate. The first version, intended for the control group, included no prompt about a possible sea level rise. The second group received a prompt emphasizing the risk of a sea level rise by 2050 due to climate change. The third group was relayed the same information as the second one, and was also given the map from Climate Central showing clearly the areas that would be most likely impacted by climate change. The fourth group received the same prompt as the second group, but was also given a prompt that hinted that a Vietnamese official expressed doubt in the Climate Central findings. The reason for adding this prompt is because research shows that skepticism from a minority group of experts can have the effect of muddying consensus on matters of relative scientific certainty.[11] This means it is important to assess the potential negative effect of experts decrying science, for whatever reason. The fifth group was given all three prompts that the other three preceding groups received.

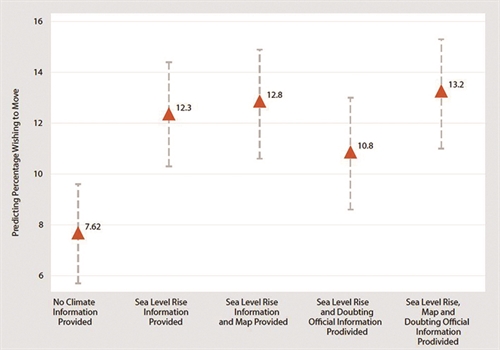

Figure 4 shows the different predicted levels of desire to migrate according to the prompts each PAPI respondent received. As can be seen, the control group, which received no prompt, had relatively low levels of desire to migrate. About 7.6 percent of respondents in this group said they would want to move permanently outside the province. The percentage of those wanting to migrate jumps substantially when citizens are given information about climate change. Simply receiving information about the risks of climate change results in a dramatic increase in the number of respondents willing to migrate, from 7.6 percent to about 12.3 percent. However, adding the map that shows which areas are most likely to be affected does not drastically increase the percentage.

|

|

What is interesting is the effect of an official expressing doubt about the scientific findings. When an official casts doubt on the science, this decreases the willingness to move from 12.3 percent to 10.8 percent. However, when the map is included, the negative comment from the official no longer reduces the impact of the information about a sea level rise. What this suggests is that the more concrete the information is, the less doubt there is among respondents, and the more the information will be absorbed.

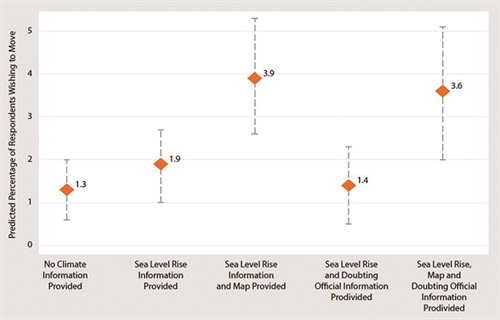

To ensure that the increase in desire to migrate was indeed due to an increasing concern about climate change, analysis about the reason given for wanting to move was conducted. This helped assess the degree to which those who received the information expressed a desire to move because of concerns about environmental conditions. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 5, the Climate Central map of where Vietnam is most prone to a sea level rise has the strongest effect. While general information does slightly increase the percentage of residents wanting to migrate for environmental reasons (from 1.3 percent to 1.9 percent), only when prompted by the map did more respondents say they would migrate (from 1.9 percent to 3.9 percent between the second group and third group, and from 1.4 percent to 3.6 percent between the fourth and fifth groups). It appears that general information about the climate may cause people to want to migrate, but not necessarily due to the climate. However, when confronted with clear and visual evidence of the impact of climate change, interest in a better natural environment is the key driver of migration.

Implications for international migration governance and climate change response policy.

|

|

The above findings also show that the desire to move internationally remains quite low in Vietnam. Most respondents who expressed a desire to move wanted to move within the country. This suggests that international migration is largely a function of opportunity - citizens will not move internationally unless directly offered the opportunity to do so. Additionally, different citizens have different reasons for moving. To avoid a tragic end to individual international migration instances, as in the case of the 39 deceased Vietnamese trying to make it to the United Kingdom, local governments should try to understand the motivations for their citizens to move abroad and proactively offer legal advice in sending areas.

Furthermore, information about a sea level rise as a result of climate change may have an impact on the desire to migrate. The findings provided in this article have several policy implications for Vietnam. They show that in the absence of information, Vietnamese citizens may underestimate the risk of climate change and express less likelihood to relocate. Clear information about climate risks increases the desire to migrate. This suggests that the Government should provide clear information about the risks of climate change so that both local leaders and citizens can appropriately assess the risks of climate change. Without transparent and clear information, local officials and citizens may, for example, also continue to overbuild in areas vulnerable to the risks of climate change.-