Andrew-Wells Dang, Nguyen Tran Lam, Le Kim Thai, and Do Thanh Huyen[1]

Introduction

As human and economic development in Vietnam has increased over the nearly three decades of Đổi mới (Renewal), people’s expectations of governance, or public decision-making, are also changing. Vietnam’s Constitution and political structure offer opportunities for citizens to participate in governance both directly (through in-person engagement at the local level) and indirectly (through voting for People’s Council and National Assembly delegates). These forms of participation can be summarised in the two familiar slogans of “People know, people discuss, people do, and people monitor”, and “Government of the people, by the people, and for the people”. Yet the implementation of legal rights to participation often lags behind the letter of the law. How can citizens be more actively involved in public decision making?

This article considers the question of increased citizen involvement based on findings from the research Between Trust and Structure: Citizen Participation and Local Elections in Vietnam, the result of collaboration between Oxfam in Vietnam and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)[2]. The report examines and analyses citizen participation in policy-making processes and political life. It forms part of a series of UNDP-commissioned studies on Vietnam’s governance and public administration performance conceived on the basis of the wealth of data and information provided by the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI)[3]. The report employs an innovative combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis to compare citizen participation at the national level with in-depth conditions in local communities.

Research into citizen participation in governance and public administration issues is of particular importance at this time considering that in 2016, the Communist Party of Vietnam will hold its five-year Congress, and elections will be held for a new National Assembly for the 2016-2021 period. With these upcoming events in mind, the article provides insights into people’s understanding and perceptions of local governance and suggests potential policy responses to address matters of concern surrounding direct and indirect participation.

Uneven direct citizen participation in local governance processes

Direct participation refers to people’s substantive involvement in local governance. Participation requires that citizens, first, are aware of local governance structures and opportunities for participation. Second, people typically participate through one or more organised groups or associations, which may be officially established (such as in the case of mass organisations) or informal and unregistered (as in local clan, lineage, and most cultural groups). Through these and other structures, people contribute to local socio-economic development programmes and policies, such as land allocation, budget formation and monitoring, or poverty reduction programmes implemented by state agencies, sometimes with the involvement or funding from international agencies or non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Citizens’ contributions may be monetary or in-kind, voluntary or required. Finally, people have important roles in monitoring implementation of local authorities, making formal complaints in case violations occur, and resolving disputes among citizens or between citizens and authorities.

These four roles of direct participation correspond to the commonly understood steps of “People know, People discuss, People do, and People monitor”. Our analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data shows that most Vietnamese citizens are aware of basic governance structures, but their awareness drops off rapidly when asked about more detailed or complex topics. Local officials interpret citizens’ low levels of knowledge as evidence of apathy or poor education. This may sometimes be the case, but citizens interviewed for the research state that they are more concerned about practical impacts of governance than about the slogans and theories used by officials.

Quantitative PAPI data shows that citizens’ knowledge and awareness of local governance is mixed. The results in Table 1 demonstrate that while a majority of respondents have heard of the “People know, discuss, do, and monitor” concept, the respondents are most likely to be aware of the Grassroots Democracy Ordinance (GDO). Awareness of the GDO has actually declined since 2011, when it was 34 percent overall. These results raise important questions about the usefulness of these structures. Concerning village heads, which are the leaders closest to most citizens, extremely few respondents are aware of their correct term of office. As expected, men, members of the Kinh majority, people with good economic status, and people with connections to authority showed higher knowledge and awareness, especially on more detailed questions. Urban residents also had slightly higher rates of positive responses, but this difference was not very large. (See Table 1)

Table 1. Selected national PAPI results (2013): knowledge and awareness of local governance processes

| Description | Natl Avg | Sex | Ethnicity | Rural | Urban | Econ level | Connected | ||||

| M | F | Kinh | EM | Good | Less | Y | N | ||||

| Could correctly identify 3 main local governance positions | 73% | 80% | 67% | 73% | 76% | 71% | 79% | 73% | 73% | 82% | 72% |

| Aware of Grassroots Democracy Ordinance | 27% | 34% | 21% | 29% | 19% | 26% | 32% | 37% | 26% | 61% | 25% |

| Aware of slogan ‘People know, discuss, do, monitor’ | 66% | 74% | 58% | 68% | 49% | 64% | 72% | 78% | 64% | 92% | 63% |

| Know that term of village heads is 2.5 years | 10% | 13% | 7% | 10% | 6% | 10% | 9% | 19% | 8% | 32% | 8% |

Qualitative field interviews shed light on citizens’ knowledge and awareness beyond the findings of PAPI. Interviewed citizens took a practical view of the effects of governance structures on their daily lives. In Quang Tri, which scored highest on PAPI in 2014, respondents could tell when the latest elections happened, what the correct terms of village heads are, and who are members of the commune People’s Council. In the other provinces visited, many respondents were unable to answer these questions. One group of citizens could recite the “People know” slogan, but when it came to “People monitor”, they said they were not clear what they were expected to be able to monitor. Numerous respondents could not remember clearly how the commune People’s Council is elected or who its current members are, which would make informed voting decisions difficult. A few respondents showed confusion between the People’s Council (Hội đồng Nhân dân) and People’s Committee (Ủy ban Nhân dân), which they only referred to collectively as “the authorities” (chính quyền). In short, awareness of the “People know” slogan or the GDO does not necessarily equate to understanding of their contents.

Individual interview respondents from the Vietnam Fatherland Front and state agencies frequently interpreted low levels of knowledge as apathy. “They care little about politics. They do not even know the chairman of their commune,” said one cadre about the surrounding population. In urban and more developed areas, citizen apathy was explained on the basis that politics were not important to most residents, and in rural and mountainous areas, because people are too busy working to make ends meet to have time to pay attention to public issues. If either perception is accurate, this suggests a need for re-thinking the design of any programme that aims to increase citizens’ knowledge as the basis for improved governance. Local cadres are well informed about policies concerning participation, often able to explain them in legal and theoretical terms. Ordinary citizens, by contrast, understand policies in terms of practical impacts, to the extent they are aware of them at all.

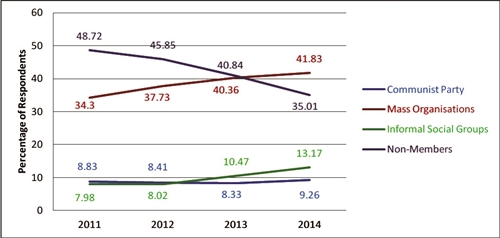

People participate in public life largely through groups of all kinds: formal associations, informal social gatherings, and many intermediary forms. Vietnamese citizens participate in a wide array of mass organizations and informal social groups at the grassroots level. Annual PAPI survey data since 2011 indicates that associational membership may be increasing nationwide over time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Changes in Associational Membership (PAPI 2011-2014)

|

Qualitative research results offer a more nuanced picture, in which membership is strong in some locations and among some citizens whilst remaining weaker for others. Participation in associations, however, does not necessarily equate to active involvement in socio-economic development, such as land use, development planning, or budget monitoring. Meanwhile, citizen monitoring of local government performance through vertical accountability structures forms the lowest performing area of direct participation, with People’s Inspection Boards (PIBs) and Community Investment Supervision Boards (CISBs) often not functioning as designed. Regardless, each of the research locations visited exemplified certain positive governance practices to be recognised and highlighted.

Whilst participation in associations involves charity, public events, and social activities, the category of “socio-economic participation” covers land issues, budget monitoring, and voluntary contributions to local development (which is usually interpreted to mean infrastructure construction.) Overall, participation in socio-economic issues is consistently lower than participation in associations, likely because citizens see less direct benefit from their involvement. The level of participation is relatively higher on issues which affect people’s livelihoods most directly. Those citizens with strong connections to mass organisations or local authorities are more likely to engage actively in socio-economic issues.

Citizen interviews demonstrated a relatively high level of interest and concern about land issues, compared with lower attention to budgets and socio-economic development planning. Levels and attitudes towards participation vary according to gender, ethnicity, and age, with migrant workers participating the least. The major mechanism for citizen feedback is the village meeting. In research locations, citizens stated that village meetings take place either quarterly or semi-annually (if the latter, to coincide with semi-annual meetings of the commune People’s Council). In one commune of Quang Tri province, for instance the local budget is discussed semi-annually and the commune socio-economic development plan once annually. Respondents emphasised that village meetings are the most effective channel for local people to raise concerns with local authorities. An estimated 70-80 percent of households send representatives to attend meetings.

According to one focus group participant in Hoa Binh, the level of personal involvement has improved over time: “Participation is better now, when I go to meetings I speak up a little more…and try a little harder”. In Phuoc Tan commune, Ninh Thuan, 38 percent of households are poor (and 96 percent ethnic Raglai), yet participation in socio-economic activities is no lower than in urban areas. Attendance at village meetings is reportedly high, and meetings combine discussion on local land use, farming and social issues with reports on commune and district plans. These plans, however, are not open for discussion.

In other locations, citizens stated (and local officials complained) that participation is frequently superficial or “in name only” (hình thức). In one commune of Hoa Binh province, meetings are said to be mainly held for the purpose of informing local people about policies and plans already decided by authorities. Often, perhaps as a result of the lack of substantive discussion, attendance is low. As a result, citizens do not receive enough information about policies and are rarely able to affect their implementation. Some local authorities viewed the “low educational level” of citizens as an explanation for weak participation; low knowledge and awareness could also be seen as a result of limited opportunities to contribute. Even when people come to events and meetings, they are not substantially involved in decision making and are often unaware of final decisions made.

In comparison to land use, budget issues and socio-economic development planning attract comparatively little interest among citizens in the research locations. As one local leader states in Hòa Bình,

On local budget transparency, it is difficult to invite all people to participate. Local people do not care much about the local budget since they are busy with their daily lives. Local authorities also find it difficult to gather people’s opinions on budget when they do not have the authority to decide how big the budget is. Hoa Binh is a poor province and still relies on the central budget. So local authorities do not have much freedom in deciding on the local budget. Direct participation of people depends on if there is an inviting environment for the participation, even in ethnic minority communities.

Responses on voluntary contributions show the same mixture of active participation and passive unconcern. Focus group interviewees in Hoa Binh, which has high rates of contributions, stated that they involve in supervising the construction of public works in their village because local people contribute a big part of the works’ investment. This contrasts with their lack of attention to the commune budget and social-economic development plan. Similarly, in Phan Rang city, Ninh Thuan, citizens participate in multiple meetings before, during and after construction projects, which are paid for by between 40-60 percent local contributions. In the upland research location in Dakrong district, Quang Tri, respondents cited poverty as a reason for the low level of contributions.

A common finding across interview locations is that youth participate at a lower rate than older residents. Many young people leave home to study and work in other provinces and cities, some of them permanently. Out-migration of youth is a significant factor in all research locations except for Phan Rang city. In rural locations, as many as half of all families have one or members working away from their home province (as many as 700 youth from one commune in Quang Tri, and 40 percent of the population in a commune of Hoa Binh province), including a small number working as export labourers in other Asian and Middle Eastern countries. With few active local youth, the Youth Union plays a limited role, concentrating mainly on charitable events and feasible local projects such as on sanitation and road safety.

Ethnic minorities, as noted above, have somewhat fewer opportunities to participate in socio-economic issues than Kinh citizens overall, but are at least as likely to make voluntary contributions for public works. Levels of participation for specific ethnic groups in specific locations may vary widely, as qualitative research showed with Raglai in Ninh Thuan, Van Kieu and Paco in Quang Tri, and Muong and Thai in Hoa Binh. In Dakrong district, Quang Tri, the quality of local governance was demonstrably less than in the Kinh lowlands, but this effect was not noticeable in the other provinces. One factor is constant in all ethnic minority areas: printed information, such as budgets and land-use maps, is available only in Vietnamese and not in any ethnic languages. Even when explanations are given in local languages during village meetings (which can happen in areas where one ethnic group forms a strong local majority), the style of discussion with many abstract terms such as “socio-economic development planning” may not encourage active participation.

Discrepancies in indirect participation in representative political institutions

Indirect or representative participation, as described in the Introduction, refers to the election of village heads, delegates to People’s Councils (at commune/ward, district, and provincial levels), and delegates to the National Assembly. Like other single-party states around the world, Vietnam uses elections to confirm the legitimacy of the ruling party, give citizens a partial voice in selection of candidates for certain leadership positions, and provide a check on accountability and effectiveness of political leaders at the local level. According to the 2013 Constitution, “The elections of deputies to the National Assembly and People’s Councils shall be conducted on the principle of universal, equal, direct and secret suffrage” (Article 7). Further legal requirements for elections are set out in the Law on People’s Council Elections (2003), Law on National Assembly Elections (2010), and the Grassroots Democracy Ordinance (for village head elections).

The analysis in this section focuses on election of village heads and commune People’s Councils. These elections are conducted separately: village heads (and neighbourhood block leaders in urban areas) are elected for terms of 2.5 years, while commune and ward People’s Council elections take place every five years together with national elections for district/provincial People’s Council and the NA. We first examine election processes for both village head and People’s Council elections by comparing PAPI survey results and qualitative interview data with legal provisions of how elections should be run, paying particular attention to who does and does not cast ballots directly. The discussion then turns to the important questions of candidate nomination and selection for village and commune offices: whose names appear on the ballot, and what qualities do voters look for in electing local representatives? Answers to these questions relate not only to technical questions of election administration, but also illuminate a balance between central control and lower-level responsiveness in local political structures.

Regarding elections, the research notes discrepancies between the very high nationally reported turnout and PAPI data on election participation. Official turnout in Vietnamese elections is extremely high by global standards. The most recent national election, in 2011, achieved a stated turnout of 99.51 percent nationwide; in several northern provinces, among them Hoa Binh, the reported turnout reached 99.99 percent. PAPI survey results have consistently shown different results: the percentage of surveyed citizens who said that they voted in person in the 2011 national election was 66 percent. For village head elections, which are held more frequently, PAPI findings have remained between 66-73 percent, with the highest reported participation recorded in 2012.

It is argued that a large portion of this gap can be explained by the prevalence of proxy voting by family members, which is legal in village elections and overwhelmingly acts to disenfranchise women. Constitutional guarantees of election quality are realised in elections of deputies to the National Assembly and People’s Councils more than in village head elections, and more consistently in some locations than others. In addition to women who do not vote in person, youth and migrants are under-represented in local elections, which often do not meet Vietnam’s own standards for equality and secrecy. For voters, trust or confidence (uy tín), sometimes also stated as “morality” (đạo đức), is the most important characteristic in choosing elected representatives, rather than policy positions. To officials, the key qualification is candidates’ education level (trình độ or năng lực). Authorities maintain a “structure” (cơ cấu) to promote representation of all social groups in People’s Councils (and the National Assembly). The exact composition of the structure varies by location, but the result is that candidates are selected on the basis of a mixture of meritocracy and corporatism.

In all research locations, national elections (for People’s Councils and NA) were described as “like a community festival”: citizens put on their best clothes, and “everyone is told to stop working and go to vote”. Almost 100 percent of local people participate in the festival, said focus group interviewees in Ninh Thuan. Village and commune officials invite everyone to vote, and “after having been invited, we have to go!”. The only people who do not come to vote, in this perhaps idealized picture, are those too elderly, ill or disabled to come to the polling station - and in these cases, election officers bring ballots directly to them at their houses, consistent with Article 50 of the Law on Election of Deputies to People’s Councils.

PAPI results show that most village head elections satisfy the criteria of secret ballots and no influencing of voters’ selections, while the criteria of public counting of results is met about two-thirds of the time. However, only slightly more than half of PAPI respondents said that at least two candidates were nominated for village head. (In the provinces visited in this study, over 70 percent of village elections were competitive in Hoa Binh and Quang Tri, while for Ninh Thuan this figure was 47 percent, and only 36 percent for ethnic minority respondents.) Proxy voting in village elections, at 28 percent, when added to those who voted directly, equals 98 percent or almost the officially reported election turnout. In Hoa Binh, only 36 percent of women voted directly in person; the remainder reported that someone else voted on their behalf. PAPI data also suggests that proxy voting is nearly as common in urban areas as in the countryside. While some women also apparently voted as proxies for men, the overwhelming effect of proxy voting is to disenfranchise women in village elections, calling principles of universal and equal suffrage into question.

Suggested ways forward for improvement in citizen engagement

Beyond analyzing the current situation of participation in political life, the research team asked both individual and focus group respondents their views on a set of potential electoral reforms that are either already piloted or proposed in Vietnam. All ideas were supported by at least some respondents, though levels of acceptance varied widely among both citizens and local officials. The reforms with the highest overall support were a change in election procedures to guarantee “one person, one vote” and a restriction on the number of dual appointments between government and elected bodies.

Qualitative research on direct and indirect participation in local governance, combined with analysis of PAPI data, reveals a number of specific ways in which implementation of citizens’ constitutional rights, laws and policies on grassroots democracy and elections can be promoted within the present Vietnamese political system. Efforts to promote substantive participation are already being made through pilot and experimental programmes of the Vietnamese government, donors, and international and domestic NGOs. These programs should be expanded and promoted with cooperation of local authorities and mass organizations, particularly the Fatherland Front.

Specifically, the report recommends the following actions to increase direct participation in governance:

l Clarify and increase implementation of mechanisms for citizen input to local authorities, via the Law on Local Government, Grassroots Democracy Ordinance, related decrees and government programmes.

l Expand innovative and informal channels for citizen feedback via NGOs and technology-based surveys and scorecards.

l Merge PIBs and CISBs to form citizen supervision committees, under the oversight of People’s Councils.

l Promote the use of ethnic minority languages, as stipulated in the Constitution, in order to increase participation of all ethnic groups.

To improve electoral participation, several important steps can be immediately implemented before the next national elections in 2016:

l Apply one set of common laws and procedures to all elections for village heads, People’s Councils and National Assembly.

l End the practice of proxy voting to ensure the direct voting rights of women, youth, and migrants, in accordance with Constitutional requirements for ‘universal, equal, direct and secret suffrage’.

l Increase the diversity of local candidates, reducing the practice of dual appointments.

l Deploy domestic election monitors, in particular during popular consultation processes (hiệp thương) to verify increased election quality, in cooperation with mass organizations and other social institutions.

In the medium term, participation can be further strengthened through policy changes and re-structuring in the medium term that will meet the interests of citizens and authorities alike, improving governance and public administration quality to sustain Vietnam’s pace of human development. Among our recommendations for the next five years are:

l Standardize village elections as part of the five-year national election cycle, with a single set of election legislation applying at all levels.

l Increase the role of People’s Councils at all levels.

l Require that People’s Council (and National Assembly) members are professional representatives without dual appointments in the government system.

l Balance budget allocations for quality local governance, reducing infrastructure construction and promoting streamlining of some Party and government functions.

Such reforms to enhance citizen participation would promote effectiveness and stability in politics and society. A key feature of the Đổi mới period has been the responsiveness and openness of state authorities, which has spurred human and economic development. The present trends towards lower citizen involvement, as seen in lack of change or decline in PAPI scores on participation-related measures, are a sign that it is time to promote further responsive reforms. Achieving this goal will require the efforts of Vietnamese citizens and political institutions alike.-