The 2020 Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) Report,[1] released on April 14, 2021, assesses citizen experiences with national and local government performance in governance, public administration, and public service delivery at the provincial level.[2] Apart from national and provincial findings on governance and public administration performance from permanent residents, in 2020, the PAPI research outreached temporary residents in six largest internal migrant-receiving provinces to understand how temporary residents perceive of and experience with local governments’ performance in governance and public service delivery. This article introduces key findings from this pilot study.[3]

Center for Community Support and Development Studies, Vietnam Fatherland Front Center for Research and Training, and United Nations Development Program

Introduction

Migration is an increasingly central concern in Vietnam. Inter-provincial migration has become an important trend over the past decade as Vietnam develops into a complex economy with growing concentrations of industrial activities and urban centers with rapidly growing service sectors. According to the 2019 Census, 12 of Vietnam’s 63 provinces have received noticeable shares of migrants from other provinces over the past decade.[4] In major industrial provinces like Binh Duong, Dong Nai and Bac Ninh, the share of migrants moving into the province (the in-migration rate) is over five times the share of those leaving (the out-migration rate). To put this in stark relief, in Binh Duong the net migration rate (in-migration over out-migration) is over 200 percent. As a result, among every five residents over five years old (2.3 million people) in Binh Duong, one person is a migrant from another province (489,000 people). Similarly, in Hanoi, Da Nang and Ho Chi Minh City, urbanization and employment opportunities have been major factors pulling in migrants from other provinces.

This article reflects on a pilot effort to include non-permanent residents in the 2020 PAPI survey in order to better understand how migrants are experiencing governance in the six provinces with the highest number of internal migrants (Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Bac Ninh, Da Nang, Dong Nai and Binh Duong). It first discusses the research design of the pilot effort. It then presents the results of the analysis and discusses how they will inform future iterations of the PAPI research agenda.

|

| Carrying out procedures for grant of chip-based ID cards for people in Ho Chi Minh City__Photo: Thanh Chung/VNA |

Growing internal migration in Vietnam and its impact on local governances

Over time, internal migration has begun to affect the precision of PAPI data and findings. Since its origin in 2009, the PAPI sampling strategy has focused on permanent residents (or those with the hộ khẩu (household registration) status in the surveyed commune, district or province).

The reasoning for this approach was four-fold. First, the research team was trying to maintain equity across provinces to allow for fair comparisons. Because migrant shares differ significantly, the team worried that including migrants might unfairly move scores up or down, depending on migrants’ experience with government. Second, according to the 2013 Law on Residence, only permanent residents can access all local public services. Those with temporary resident status need to return to their home provinces for their personal paperwork, such as marriage certificates and birth certificates, to obtain government certification of documents and to access public services. As a result, the original PAPI research team did not feel that migrants would have enough knowledge about public administration and services in their new homes to be able to answer the detailed survey questions.

A third factor for considering altering the PAPI sampling strategy is that migration has become highly relevant in national policy discussions. In 2020, the National Assembly began discussing migration reforms in the amendment to the 2013 Law on Residence and many expected that the priority status of permanent residency versus non-permanent residency would be removed.[5] Finally, the publication of the 2019 census data provides a more accurate picture of demographics and migration, allowing the research team to improve the sampling strategy.

As a result of the national importance of internal migration and the opportunity costs of an empirical study built solely on permanent residents, the PAPI research team decided to experimentally expand its sampling scope to include migrants in the six provinces mentioned above. The purpose of the expanded sampling strategy was two-fold: (i) to reflect the opportunities and challenges the receiving provinces are facing while welcoming more people to their provinces; and (ii) to understand how inter-provincial migrants experience services in their new home provinces.

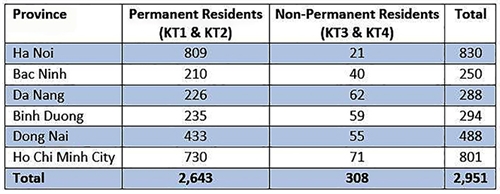

The first decision was to focus on Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Da Nang, Binh Duong, Dong Nai and Bac Ninh, which are the six largest migrant-receiving provinces according to the 2019 Census. In order to optimize budgetary and time resources, the research team built the migrant sample into the original cluster sampling strategy, which sequentially selects districts, communes and villages through cluster and probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling procedures, and ultimately individual respondents through random sampling. Target provinces were divided into two groups. In the three large sample provinces of Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City and Dong Nai, migrants were surveyed in eight randomly selected villages of the 24 sampled villages. In the smaller sample provinces of Da Nang, Bac Ninh and Binh Duong, additional migrants were sampled in all villages.[6] The following analysis compares the answers of the 308 non-permanent respondents to the answers of the 2,643 permanent residents from the same provinces (see Table 1).

|

|

Migrants differ markedly from permanent residents in 2020

|

|

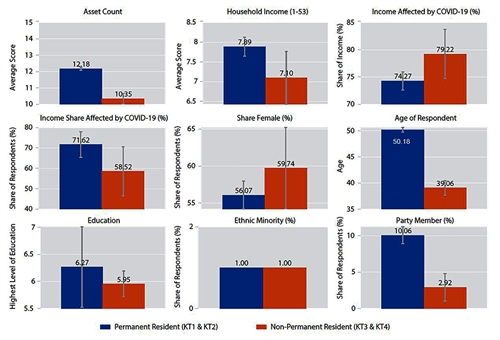

Figure 1 presents a series of bar graphs that show demographic differences between migrants and permanent residents. The blue bar represents the responses of permanent residents, while the orange bar represents migrant responses. The grey range lines at the top of each bar represent 95 percent confidence intervals. When these lines do not overlap (the maximum range of the lower group is not higher than the minimum of the lower group), it is possible to conclude that the differences between the two samples are statistically significant and not an artefact of this particular sample.

The graphs inside Figure 1 show clear differences between the demographics of migrants and permanent residents. Migrants tend to be poorer with less household assets, with about a two-item difference on a 20-point count of items such as televisions and motorcycles.[7] They marginally have less income. They are also about 11 years younger on average, are less educated and are more likely to be female. They are dramatically less connected: only 3 percent are likely to be party members, compared to 10 percent in the permanent resident sample. These demographic differences explain why migrants’ experience with governance may be worse, as they lack the education and government connections to adequately advocate for themselves.

Migrants experience significantly worse governance in 6 largest receiving provinces

|

|

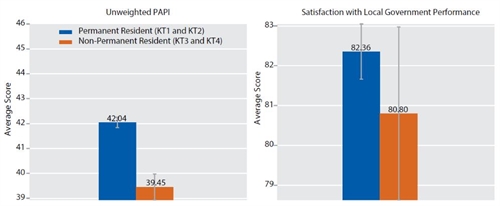

Figure 2 explores the hypothesis that migrants experience worse governance than other residents in the same province. To do this, separate unweighted PAPI indices for provincial residents and migrants were created. The figure shows that migrants rank the overall governance in their locality about 2.5 points lower (39.5 versus 42) on the 80-point PAPI total score. To put this number in perspective, the lowest provincial score in the 2020 PAPI survey is 40.1 points, which means that the governance experienced by the average migrant is worse than that experienced by residents in the worst performing province in the country. Furthermore, the 2.5 points difference in governance between migrants and permanent residents is the same distance between the median province in the 2020 PAPI survey (ranked number 32) and the fifth ranked province. The bottom line is that migrant residents interact with the local bureaucracies in their current province much less than permanent residents. This same sentiment is reflected in the right panel of Figure 2, where citizens’ satisfaction with their local government performance is displayed using a 100-point feeling thermometer. To create this measure, the average assessment of provincial, district, commune and village leaders is calculated. As can be seen, migrants rate local officials that they interact with at 80.8 points, compared to 82.4 for permanent residents.

Governance gap differs by receiving provinces in 2020 PAPI

|

|

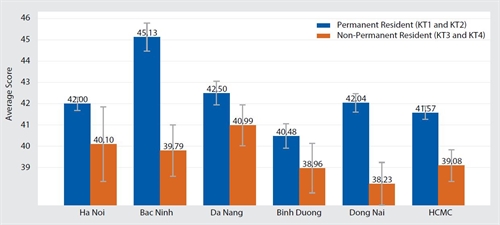

The governance gap between migrants and permanent residents in each of the six provinces is shown in Figure 3. While there are differences between the two groups in every province, the differences in the gap size are quite stark. Migrants in Bac Ninh experience the greatest inequality, with a 5.3 points difference between their unweighted PAPI scores and those of permanent residents. In Dong Nai there is a gap of 3.81 points, while Ho Chi Minh City with a gap of 2.49 demonstrates moderate inequality. By contrast, migrants in Da Nang have the best experience with local officials, with their unweighted PAPI score the highest in the country at 41 points, only 1.51 points below the governance assessment provided by permanent residences. Hanoi and Binh Duong also demonstrate smaller gaps, but also lower overall governance scores for migrants.

The gaps in governance dimensions are large for migrants in each of the eight PAPI dimensions

|

|

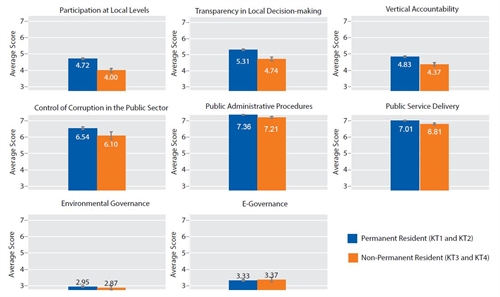

Figure 4 looks at the gap in governance for migrants in each of the eight PAPI dimensions. It is quite clear that the differences are most pronounced in the first four dimensions (Participation at Local Levels, Transparency in Local Decision-making, Vertical Accountability, and Control of Corruption in the Public Sector). By contrast, there are very few differences between migrants and permanent residents in their experience with Public Administrative Procedures, Public Service Delivery, Environmental Governance, and E-Governance. That the largest gap is in political participation makes sense, as non-permanent residents are not included in local decision-making institutions. However, the other scores are more surprising. Migrants claim to have significantly less access to information, are less able to file complaints or connect with local officials and are more exposed to bribe requests by unscrupulous bureaucrats.

Implications for migrant receiving provinces

The findings above imply important public policy that should be considered for provinces that receive internal migrants. Findings from the pilot analysis of migrants in six provinces within the 2020 PAPI research show that there are significant demographic differences between migrants and permanent residents. Migrants tend to be poorer, less educated, more female and less connected to party and government officials. Thus, in addition to being outsiders, they also lack the resources to advocate for themselves in interactions with the bureaucracy. Correspondingly, there is a significant gap in their experience with governance compared to permanent residents in the same village.

In fact, the average migrant PAPI score is significantly lower than that of permanent residents in the province with the lowest PAPI scores. This gap in governance is most pronounced in the first four dimensions of PAPI. Migrants clearly have less access to formal channels of participation and accountability and to local complaint mechanisms. More surprising, however, is that they have less access to information and are more exposed to bribe requests from unscrupulous officials, who likely know they have less resources to dispute and protect themselves. The gap in migrant experience varies heavily across provinces. In Da Nang, the governance experienced by migrants is not much lower than that experienced by the average permanent resident. In Bac Ninh, on the other hand, there is a more than five points difference between the experience of migrants and that of permanent residents.

Efforts to narrow these gaps would be the equivalent of moving a province in the bottom five provinces in the country to the top five on the PAPI index. This means that migrant-receiving provinces will need to double their efforts to adequately address the needs and expectations of both permanent and non-permanent residents. More importantly, it is a time for Vietnam to remove the hộ khẩu status and to apply universal identification numbers, so that every citizen can access all governance and public services equally in every province within the country.-