Introduction

Migration remains an issue of prime concern in Vietnam. Disparities often encountered by growing numbers of migrants were further amplified in 2021 by the unprecedented social and economic losses left behind by COVID-19 as it swept across the country and recent economic uncertainties because of disruption of global supply chains. As such, there is a critical need to identify and explore gaps in access to good governance and quality public services between migrants and permanent residents in receiving provinces as well as drivers of migration within Vietnam in 2021, which result in wide-ranging social and economic impacts in need of agile and inclusive policy responses.

This article is the third excerpt from the 2021 PAPI Report, after the national and provincial overviews published on Vietnam Law and Legal Forum magazine in May and June issues of 2022.[2] First, it presents key findings about the gaps in access to good governance and quality public services experienced by migrants and permanent residents in receiving provinces across the eight PAPI dimensions (i.e., Participation at Local Levels, Transparency in Local Decision-making, Vertical Accountability, Control of Corruption in the Public Sector, Public Administrative Procedures, Public Service Delivery, Environmental Governance, and E-Government). In 2021, the PAPI survey also engaged 1,042 non-permanent residents from the 12 provinces with the highest numbers of internal migrants, apart from permanent adult residents, to understand how internal migrants assess their host provinces in terms of governance and public service delivery. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 exacerbated governance challenges for migrants themselves, residents and local governments in receiving provinces compared to what was observed through the 2020 surveys.

Second, this article zooms in findings about the Vietnamese population’s choice of preferred destinations for domestic and international migrations and the reasons why they would leave their home provinces from the 2021 PAPI sample of 15,833 respondents from the age of 18 years randomly selected from across Vietnam.

Third, it looks at the willingness of citizens to learn about the effects of international trade liberalization on their livelihoods and whether it would affect any decision to migrate. In this case, the 2021 PAPI survey looked at Vietnam’s entry into the European Union-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA) on a hypothesis that, on average, citizens (particularly migrants) facing income insecurity would be more likely to take the time to understand the effects of major economic changes in their localities.

Finally, this article suggests policy implications for central and local governments to act upon to ensure equality between temporary and permanent residents, especially during health emergencies and economic uncertainties, while guaranteeing their right to freedom of migration within the country.

Migration impacts on local governance

This section presents findings on migrants’ perceptions of and experiences with local governance and public services as well as drivers of inter-provincial migration. The 2021 PAPI survey repeated the previous year’s module, which asked long-term and short-term migrants about their experiences in receiving provinces. As reported by the state media between September and December 2021, about 1.5 million temporary migrants left migrant-receiving provinces under full or partial lockdowns to return to their home provinces. The 2021 PAPI survey, however, could reach a sizable population of 1,042 migrants in selected 12 receiving provinces with the highest numbers of internal migrants.[3] This helps provide important insights to understand how internal migrants assess their host provinces in terms of governance and public service delivery.

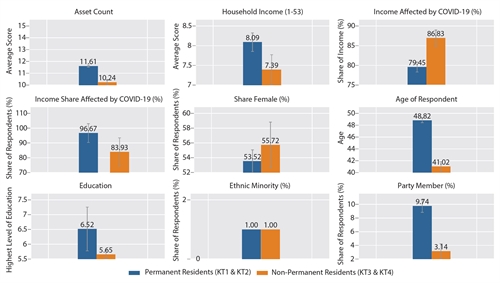

Findings from the survey show that, there are clear differences between the demographics of migrants and permanent residents (Figure 1). Migrants tend to be poorer with fewer household assets and marginally less income than residents. They are about seven years younger on average, less educated and more likely to be women. Most dramatically, they are significantly less connected: only 3.14 percent are likely to be Party members, compared to 9.74 percent in the permanent resident sample.

|

| Figure 1: Differences in demographic characteristics of permanent residents vs. migrants, 2021 |

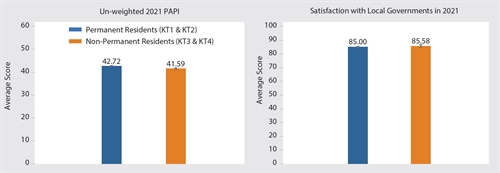

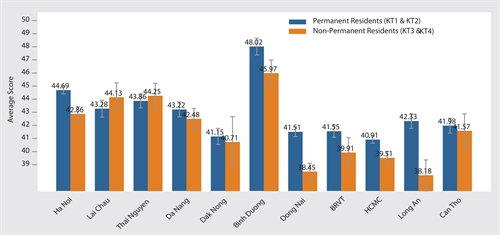

The demographic differences highlighted above reveal that migrants encountered sub-optimal local governance experiences in 2021, also observed in the 2020 PAPI Report.[4] Migrants and permanent residents reported different local governance experiences, as shown in the left graph of Figure 2. Migrants scored provinces of destination at 41.6 on the scale from 10 to 80 points of the aggregate PAPI score, compared to 42.7 given by permanent residents of the same provinces.

|

| Figure 2: Differences in governance and public administration as experienced by migrants in migrant-receiving provinces, 2021 |

The 2021 difference of just over one percentage point appears small, but is statistically significant[5] and substantively meaningful in that it is equal to one-half of a standard deviation. To put this number into perspective, if migrants were in a province on their own, they would have the second lowest PAPI ranking of all 63 provinces and the gap to catch-up with the level of governance experienced by residents would require them to leapfrog 10 other provinces.

Surprisingly, however, both residents and migrants reported equal satisfaction with local governments when asked about their perception of performance, as shown on the right graph of Figure 2. These scores may be infused with reactions to the second year of the pandemic.

When broken down by 11 receiving provinces (Figure 3), migrants in Long An experienced the greatest inequality in governance, measured by the difference between migrant and resident perceptions. In contrast, migrants in Lai Chau and Thai Nguyen reported better experiences with local officials. It is worth noting that in both provinces, the migrants tend to be Kinh people moving into minority locations in pursuit of jobs in the tourism sector.

|

| Figure 3: Governance divide as experienced by migrants in migrant-receiving provinces, 2021 |

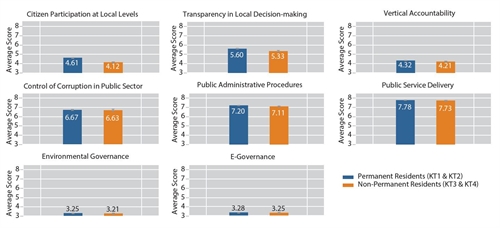

The resident-migrant differences were largest in the PAPI dimensions of Participation at Local Levels and Transparency in Local Decision-making (Figure 4). As per Vertical Accountability, Environmental Governance and E-Governance, both groups shared the same low assessments. Also, both groups shared some good experience with Public Administrative Procedures and Public Service Delivery.

|

| Figure 4: Differences in governance and public administration as experienced by migrants in migrant-receiving provinces, by dimension, 2021 |

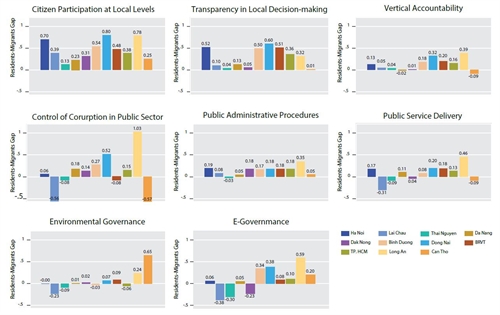

When examining the gaps by migrant-receiving provinces (Figure 5), residents in Binh Duong, Dong Nai, Hanoi and Long An claimed more opportunities to participate at local levels and have greater access to information than migrants. Residents in Long An experienced significantly lower corruption than migrant peers. However, the situation was reversed in Can Tho and Lai Chau, where migrants reported less exposure to bribe requests and informal charges.

|

| Figure 5: Differences in governance and public administration as experienced by migrants in migrant-receiving provinces, by province, 2021 |

Preferred destinations and drivers of migration within Vietnam

This section examines motivations for migration among the Vietnamese citizens in 2021. It presents the 2021 PAPI survey results about citizen choices of destinations for internal migration, communities of origin and drivers for migration (economic opportunity, governance quality, family reasons and disasters, among others). All 15,833 respondents in the 2021 PAPI survey had the chance to share their views. The survey results are expected to help inform central and local governments about key policy areas to respond effectively to migrants’ concerns and what drives them away from home communities, especially during health and disaster crises.

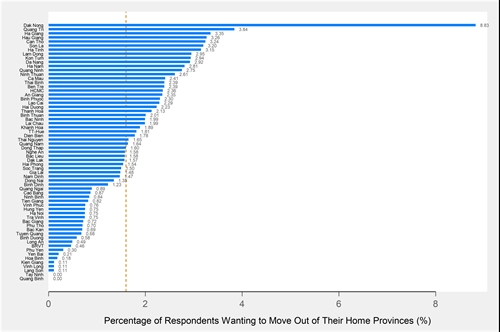

|

| Figure 6: Percentage of respondents who want to move out of their provinces, 2021 |

Compared to the 2020’s findings,[6] fewer respondents (1.6 percent) nationwide reported an urge to move permanently outside of their home province in 2021. This might be because of the spreading COVID-19 pandemic during the second half of 2021 that kept people from wanting to move. As shown in Figure 6, a critical exception was Dak Nong, where nearly 9 percent of citizens were interested in moving. Nevertheless, even in this Central Highlands province, the proportion of potential migrants fell by more than half from that reported in 2020. An open policy question is what is driving residents away from the young province of Dak Nong, which was established in 2004.

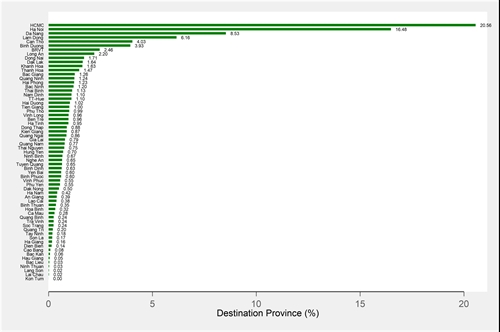

Meanwhile, the top six preferred destinations for those wanting to move in 2021 in order of preference were Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, Da Nang, Lam Dong, Can Tho and Binh Duong, while the least preferred destinations were Kon Tum, Lai Chau, Lang Son, Ninh Thuan and Bac Lieu (Figure 7).

|

| Figure 7: Preferred destinations by percentage of respondents wanting to move, 2021 |

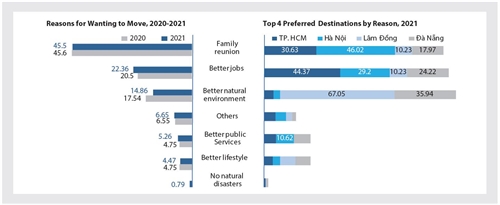

Three key reasons for respondents across the country wanting to move in 2021 dovetailed with those in 2020, including family reunions (primarily for those who wanted to move to Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City), better jobs (to Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi and Da Nang) and a better natural environment (to Da Nang and Lam Dong) (Figure 8).

|

| Figure 8: Reasons for wanting to move from 2020-21, and top four preferred destinations in 2021 |

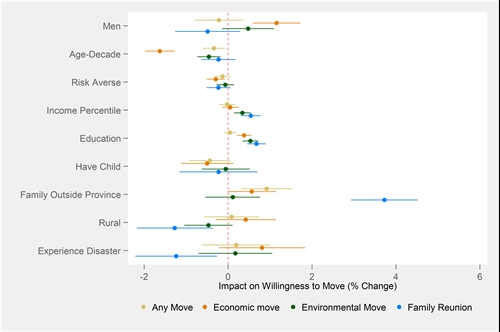

Having family outside a province strongly predicted residents’ willingness to move, particularly for family reunions (Figure 9). In addition, men and younger people are more willing to move, particularly for better jobs. Surprisingly, experiences with disasters and climate events did not heighten the willingness to move.

Migrants’ willingness to learn about economic opportunities from trade liberalization

The strong role of jobs in inducing migrants to leave their home provinces, as the previous section shows, generates an important set of questions about how they learnt about those employment opportunities and their willingness to familiarize themselves with factors that might improve their economic situation and make the migration risks worthwhile. This section presents the findings from a randomized experiment associated with the 2021 PAPI survey to answer the question whether Vietnam’s increasing international economic integration might influence citizens’ willingness to learn about the effects of trade liberalization on their livelihoods.[7] The analysis shows how internal migrants might respond to the EVFTA based upon the hypothesis that, on average, citizens (particularly migrants) facing income insecurity would be more likely to take the time to understand the effects of major economic changes associated with the EVFTA.

|

| Figure 9: Drivers of migration motivations, 2021 |

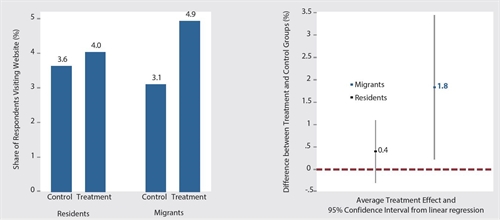

To conduct the analysis, all PAPI respondents were randomly assigned to two groups, namely the treatment group with those who received the trade literacy questions and the control group with those who did not. The treatment group was exposed to a set of questions about the economic effects of the EVFTA,[8] while the control group did not receive any priming about the EVFTA.

To proxy for willingness to learn, the key outcome variable, respondents were invited to visit a website that contains an explanatory video about the EVFTA. The video is available to all respondents who completed the survey. To match respondents who viewed the video to their survey responses, users were requested to type in a code prior to accessing the video. Respondents were handed a card with a survey identity number. The user handing out the card wrote down a four-character code, which the respondent was asked to input when visiting the website. Based on the belief that migrants are more concerned about economic uncertainty, the effects were disaggregated by permanent residents and migrants included in the expanded PAPI sample from 2021.

Figure 10 demonstrates that the experiment had no effect on the larger population or permanent residents. The trade literacy experiment did not make them seek more information online about the EVFTA. The left panel of the graph shows that, among permanent residents, 3.6 percent of the control group visited the website versus 4 percent of the treatment group. The right panel of the graph shows that this 0.4 percentage-point difference is not statistically significant, as the 95 percent confidence interval overlaps with the zero line, indicating that the difference is not statistically distinguishable from zero.

|

| Figure 10: Impacts of experiment on website searches by resident and migrant subgroups, 2021 |

Note: Control stands for Control Group and Treatment stands for Treatment Group.

By contrast, the experiment had extremely large effects for migrants. About 4.9 percent of migrants, who were exposed to the trade literacy questions, visited the EVFTA website - compared to only 3.1 percent of the control group. This difference of 1.8 percentage points is highly significant, indicated by the fact that the full 95 percent confidence interval is greater than zero.

The results indicate that migrants have more to gain than permanent residents from greater economic integration. Therefore, they were the most willing to invest time and effort in educating themselves about its consequences.

One last aspect is about the choice to migrate overseas in 2021. The 2021 PAPI survey asked the whole sample of 15,833 respondents whether or not they would move internationally for good. Only 113 respondents would move outside Vietnam if they ever left their home provinces. The top three desired destinations are the US, Australia and Canada.

Conclusions and policy implications

As this article reveals, the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated governance challenges for migrants and residents in receiving provinces. The gaps remain in access to good governance and quality public services between migrants and permanent residents in receiving provinces in 2021. Clear differences are visible between the demographics of migrants and permanent residents in receiving destinations. The demographic differences explain why migrants’ experience with governance may be worse similar to the 2020 PAPI findings. Migrant residents did not experience local governance similarly to permanent residents. The resident-migrant differences are largest in the PAPI dimensions of Participation at Local Levels and Transparency in Local Decision-making.

Inter-provincial migration will still play an increasingly pressing concern, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. As the 2021 PAPI survey results show, drivers of internal migration, including family reunion, jobs and better natural environment, mean greater demand for access to housing, employment and clean environment in preferred destination provinces. To prepare for post-pandemic waves of internal migration for such opportunities, policymakers and provincial leaders should understand how internal migrants assess their host provinces in terms of governance performance and public service delivery to enhance their inclusion as well as the pushes and pulls of internal migration.

In addition, the 2021 survey experiment on citizen willingness to learn about economic opportunities from trade liberalization also shows that economic uncertainty has a statistically significant effect on migrants. The results indicate that migrants are likely to gain the most from greater integration of Vietnam into the global economy and, therefore, they are most willing to invest time and effort in educating themselves about the EVFTA effects. The results also suggest that central and local governments disclose more information about trade liberalization policy and economic opportunities for citizens to make their own choices of employment and doing business, especially when the country has reopened its borders after the COVID-19 pandemic.-