Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry and United Nations Development Program

Introduction

This article[1] is an excerpt from the Report “Public Procurement: Findings from a Business Perception Survey”, which was the result of a collaborative research initiative conducted from July 2021 to June 2022 by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The primary data for this study came from answers to specific questions on public procurement practices in the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI) survey in 2021[2]. Highlighted here are key findings from the business survey, aiming to understand the experience and perception of businesses in public procurement activities in localities, especially in the health sector. Recommendations for the improvement of transparency, effectiveness and efficiency of public procurement in Vietnam are also noted.

The 2013 Bidding Law provides for the state management of procurement and responsibilities of concerned parties. It sets out requirements for competitiveness, fairness, transparency and economic efficiency in bidding activities. However, over the course of its implementation since July 2014, many problems have arisen in public procurement activities. Those problems include inconsistencies between the 2013 Bidding Law and other related laws that have been revised or issued recently, and obstacles in procurement procedures impeding public investment disbursement and delaying operation of works intended to serve specific socio-economic development goals, especially during the COVID-19 crisis. There have also been challenges with competitiveness, transparency and feasibility of oversight and violation settlement activities. These have contributed to increased risk of wrongdoing, corruption and waste.[3] In response to such problems, the Government issued Resolution 01/NQ-CP on major tasks and solutions for implementing the socio-economic development and state budget plans for 2021[4], in which the Ministry of Planning and Investment was assigned to amend the 2013 Bidding Law. Thus, the amendment to the law has been added to the 2023 law- and ordinance-making program, with its draft to be submitted to the National Assembly for the first discussion during the 4th session of the 15th National Assembly in 2022.[5]

The business community’s voice plays a critical role as part of these discussions. In this context, VCCI and UNDP conducted research to understand how businesses experienced and perceived public procurement, including an analysis of data on health-related public procurement activities, a topic currently drawing large public attention. In addition to summarizing key survey findings from the research, this article also highlights key recommendations for central and local governments to improve public sector performance and compliance in public procurement so as to enhance competitiveness, transparency and openness in this important field.

Key findings on businesses’ assessment of local public procurement practices

Characteristics of responding businesses

Findings presented in this article arise from the 2021 PCI survey, with a dataset comprising responses from 9,221 domestic and foreign-invested businesses operating in Vietnam. Among these respondents, 1,170 firms reported having participated in public procurement and 154 firms reported bidding to provide goods and services to public medical establishments.

The survey questions aimed to capture (i) the firms’ assessment of implementing the procedures of public procurement and (ii) the firms’ views of how their petitions, complaints and denunciations regarding public procurement are addressed at the provincial level. There was broad participation across all types of businesses, with limited liability companies accounting for the highest proportion (64 percent). Groups of sole proprietorships, joint-stock companies and others made up 9 percent, 18 percent and 9 percent of the total respondents, respectively.

Responding businesses had diverse periods of operation, ranging from newly established businesses to those that have been operating for more than 20 years. The groups of businesses operating for three to 10 years constituted 54 percent of the total business population in the 2021 PCI survey. Regarding the main economic sectors, 57 percent of the firms came from the trade/service sector and 20 percent from the construction sector - the two largest groups in the sample. Among the 154 firms engaged in health-related public procurement activities, 73 percent were in the trade/service sector and 27 percent in agriculture.

Business opportunities to join bidding at the provincial level

The survey revealed that businesses experienced many difficulties when wishing to engage in local bidding, with hurdles faced at different stages of the public procurement process: from access to bidding information, access to bidding documents, requirements for participation in bidding, to contract dispute resolution mechanisms.

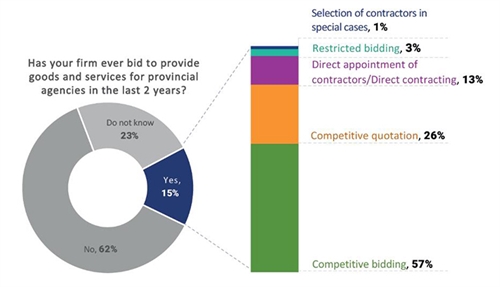

Among the 9,221 surveyed businesses, only about 15 percent said they had participated in public procurement activities over the past two years. Those who said they had not participated in public procurement in the period accounted for 62 percent, while the remaining responded “Do not know”. A barrier to participation was that public procurement often requires that businesses have certain experience and capacity meeting bidding criteria. Meanwhile, most businesses that participated in bidding and public procurement with local authorities were small-sized businesses (81 percent of them have a capital size of below VND 10 billion and 88 percent have a labor force size of fewer than 50 people) and a majority of them have had a few years of relevant business experience. The surveyed businesses operating for fewer than three years participating in bidding and public procurement accounted for merely about 7 percent of the sample.

|

| Figure 1: Percentage of businesses participating in public procurement activities and types of businesses over the past two years |

As shown in Figure 1, 57 percent of businesses that bid in the past two years said they joined “competitive bidding” with local governments, more than double the proportion of businesses participating in “competitive quotation” (26 percent). The proportions of businesses participating in direct appointment of contractors, restricted bidding and contractor selection in special cases are 13 percent, 3 percent and 1 percent, respectively.

Results reveal that 43 percent of businesses bid to provide construction and installation services - the most popular type among the groups of goods and services in the survey. Meanwhile, about 33 percent said they provided goods, 20 percent provided consulting services, and 8.3 percent provided non-consulting services. The proportion of surveyed businesses providing other goods and services was negligible.

Responses from businesses that have bid in public procurement at the provincial level showed that about 33 percent of the procuring entities were departments under provincial People’s Committees and 30 percent under district People’s Committees. The percentages of procuring entities being public schools and public medical establishments were 18 percent and 14 percent, respectively. Other public entities accounted for 17 percent.

For businesses that bid to provide goods and services for public health establishments in 2020 and 2021, the survey asked them to specify the types of procured goods or services. Among them, 29 percent revealed that they had bid to provide medical equipment, while 22 percent bid to provide pharmaceuticals. Fourteen percent of businesses reported that they had provided COVID-19-related supplies and equipment. None of the firms involved in the provision of COVID-19 vaccines participated in the survey. The largest proportion of respondents (43 percent) provided “other” these goods and services, such as services to renovate and repair infrastructure and health facilities, services related to designing, printing, provision of information technology equipment, and provision of food or other industrial hygiene services.

Business assessment of the bidding process

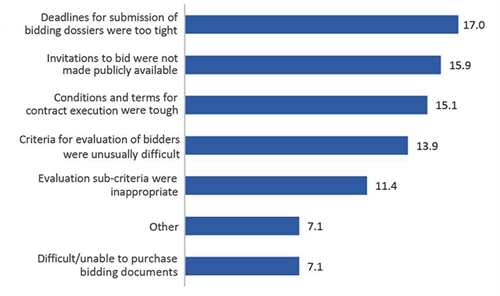

The survey asked businesses to indicate the main issues faced during the bidding process to win a contract with a local government institution.

Figure 2 demonstrates key challenges facing businesses. The short time for submission of bids was the top challenge, with 17 percent of the surveyed businesses reporting it. Next came the lack of publicity of invitations to bid (nearly 16 percent). Difficult contract terms and conditions were reported by over 15 percent. About 14 percent of the businesses reported that the criteria for evaluation of bidders’ capacity and experience given by the procuring entity were unusually difficult, while 11.4 percent said evaluation sub-criteria given in bidding requirements were inappropriate. Meanwhile, some 7 percent of the surveyed businesses had challenges with purchasing bidding documents.

|

| Figure 2: Challenges facing businesses during the public procurement process in their provinces (percentage of firm respondents) |

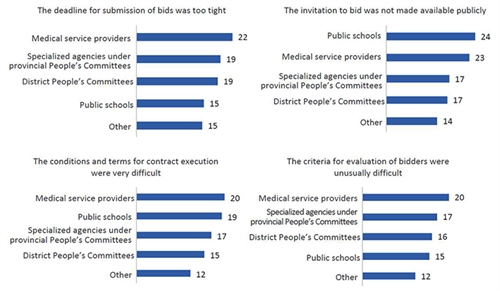

Figure 3 indicates which sector(s) the top four problems facing businesses are most commonly found in. As it reveals, 22 percent of firms participating in bids invited by public medical service providers reported that the deadline for submission of bids was too tight. Similarly, about 20 percent of businesses bidding to supply goods or services for public medical service providers mentioned obstacles in terms of difficult conditions and terms for contract execution and unusually difficult criteria for evaluation of bidders. Meanwhile, 24 percent of businesses bidding to provide goods or services for public schools said that invitations to bid were not made publicly available for them to be informed, while many businesses participating in the bid where the procuring entities are provincial departments and agencies found evaluation sub-criteria were inappropriate.

|

| Figure 3: Phenomena usually encountered by businesses during the bidding process, comparing groups of businesses based on procuring entities (by percentage of business respondents) |

Informal charges facing businesses bidding for public procurement packages

A significant problem often arising in the bidding process is the phenomenon of paying informal charges to collude and arrange bids, facilitating one party to win the bid, leading to the lack of competition and transparency in public procurement.[6] To capture how the practice is common in public procurement, the survey asked businesses to what extent they agreed with the statement that “Paying a ‘commission’ is essential to improve chances of winning the contract”.

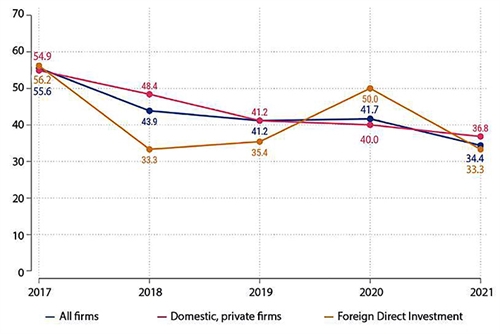

As shown in Figure 4, about 34 percent of businesses thought that paying a “commission” is essential to improve chances of winning the contract. In other words, about one out of three businesses participating in the bidding process acknowledges that success in winning a contract was unlikely without paying commissions. More domestic and private firms (nearly 37 percent) agreed with the statement than foreign-invested firms (about 33 percent). Nonetheless, Figure 4 shows a fairly positive sign that the percentage of firms perceiving a need to pay commissions to improve chances of winning the contract in 2021 was lower than those from the 2017-20 PCI surveys. This may be a result of the Party’s and State’s recent efforts in anti-corruption work, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where there has been a focus on handling a number of cases related to public procurement in the medical field since 2021.[7]

|

| Figure 4: Proportions of businesses agreeing with the statement: “Paying a ‘commission’ is essential to improve chances of winning the contract”. |

The proportion of businesses willing to pay informal charges to improve chances of winning the contract has a close relationship with the degree of “openness” of the types of bidding that they participate in. The survey results show that it is more likely for businesses to be willing to pay “commissions” in restricted bidding (70 percent) or direct appointment of contractors (51 percent) compared to competitive quotation (40 percent) or competitive bidding (27 percent). When divided by type of procuring entities, the percentage of businesses agreeing that paying “commissions” is essential to improve chances of winning a contract from a medical establishment was as high as 45 percent and from public schools was at 40 percent.

Feedback from businesses participating in public procurement in the health sector

The years of 2020 and 2021 were challenging periods for the health sector. Aside from significant challenges in COVID-19 prevention and control, the healthcare system also faced numerous problems in preventing and correcting violations in public procurement. During the pandemic, procurement of medical equipment became more essential than ever. However, the complexities of a global pandemic increased many potential risks of illegal activities such as bid rigging, forming “backyard” relations, frauds related to bidding prices, collusive overcharges for products to gain illicit profits, or “commission” shares between procuring entities, line state agencies and related agencies and contractors. For this reason, the survey included questions to help gain an understanding of how serious these problems were.

As noted earlier, the 2021 survey results show that, overall, 45 percent of businesses that responded to bidding calls from medical establishments agreed with the statement that “Paying a ‘commission’ is essential to improve chances of winning the contract”. When classifying firms by type of goods and services they provided, the data show that up to 50 percent of businesses providing medical equipment agreed that they had to pay a “commission” to win contracts. The proportions for businesses providing COVID-19 supplies and equipment, and pharmaceuticals were 38 percent and 33 percent, respectively. For other goods and services in the health sector, the proportion of businesses perceiving that paying informal charges is essential was at 39 percent.

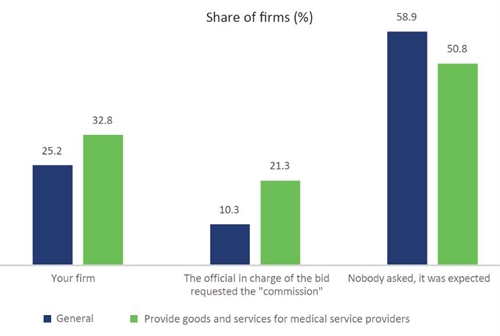

Furthermore, commission requests were often initiated by businesses or officials in charge of bidding in the health sector. However, in the majority of cases, paying commission is seen as an unwritten rule for any business wanting to join in the bidding offered by public entities. Figure 5 summarizes the survey results, indicating that nearly 33 percent of firms initiated giving commissions to arrange bids to provide goods or services for medical establishments. The proportion of businesses facing a request for “commissions” by officials in charge of public procurement in the sector was about 21 percent. It is even alarming that, nearly 51 percent of businesses bidding for medical goods and services chose the statement “Nobody asked, it was expected” as the reason for paying “commissions” to officials in charge of the bid. The study findings somewhat reflect what has happened with a rising number of trials and cases against public health officials over the past two years for having received commissions in the public procurement of COVID-19 test kits and equipment[8].

|

| Figure 5: Reasons why businesses pay “commissions” in bidding for goods or contracts with general and health-related public procurement agencies |

Non-discrimination is a key principle of public procurement. In the context of international economic integration[9], this is highlighted further when the trade and investment agreements that Vietnam signed usually have provisions on non-discrimination in public procurement. The 2021 survey has asked businesses to assess equality in the behavior of the local procuring entity. Specifically, the question was “Was your business treated equally by the procuring entity to other bidders during the bidding process?”

In the health sector, in particular, more than 30 percent of surveyed medical equipment and pharmaceutical companies reported that public procurement agencies treated them fairly, implying that the behavior of the bidding agency is not as expected in the majority of cases. Most of the businesses dissatisfied with the adherence to the principle of non-discrimination by public procurement agencies were microbusinesses with five or fewer years of operation. When dividing firms by procuring entity, the survey results showed that the proportion of businesses that were treated fairly while participating in bidding was lowest for the health sector (38 percent), while fair treatment in other sectors ranged from 43 to 48 percent.

The survey also assessed how businesses respond when they find they are treated unfairly while participating in public procurement. Firms were hesitant in choosing the method of reevaluating results of the contractor selection and any other relevant matters during the contractor selection process. Of the 32 percent of firms that disagreed with the bidding results, only 30 percent chose to send a request to public procurement agencies for reasons of why they were not being selected. Meanwhile, more than two-thirds of the surveyed businesses opted for “doing nothing” when they found they were treated unfairly in public procurement.

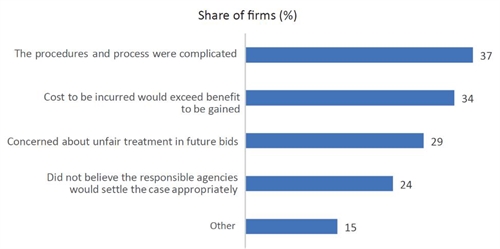

Among firms that requested for a review of bidding decisions by public procurement agencies, businesses having been operational for a longer period of time had their cases settled more satisfactorily than those having a shorter operational time. For those firms that chose to be silent when being treated unfairly (Figure 6), 37 percent said the review processes and procedures were too complicated, 34 percent were worried about the costs incurred during the review process exceeding the benefit to be gained, 29 percent were concerned about continuing to be treated unfairly when participating in a future bidding opportunity, and 24 percent reported that they did not trust the results of the settlement of petitions by state agencies.

|

| Figure 6: Reasons why businesses do not ask for reconsideration when they are treated unfairly while engaged in public procurement and bidding |

Recommendations

The survey provided a lens into how businesses perceived and experienced local practices in public procurement and bidding in Vietnam. The survey results show that public procurement needs to be further reformed both in terms of regulatory framework and policy implementation. In response to the key findings presented in this article, the following recommendations are on offer for policymakers and policy implementers.

For policymakers, the following courses of actions should be undertaken:

- Making amendments to the 2013 Bidding Law so that it clarifies the appropriate application of direct contracting and gives specific provisions on processes and procedures of direct contracting, especially in emergency cases such as disasters, epidemics or pandemics;

- Providing specific provisions on processes and procedures of direct contracting for immediate remediation or prompt handling of the consequences caused by force majeure events;

- Ensuring that the revised Bidding Law is in sync with other relevant laws like the Law on Construction, the Law on Investment and the Law on Public Investment; and,

- Reconsidering the value caps for direct contracting to match those set in international organizations’ regulations and free trade agreements that Vietnam has joined.

- Enhance dissemination of legal documents on public procurement to businesses, to ensure their compliance, and to protect their legal rights and interests when taking part in public procurement activities;

- Promote the use of the Vietnam National E-Procurement System through upgrading current technical infrastructure and strengthening the coordination between state agencies and businesses;

- Strengthen competitive bidding and competitive quotation to reduce commissioning practices in public procurement;

- Define the responsibility of the heads of procurement management agencies at the provincial level for any public procurement involving violations committed in their jurisdiction;

- Enforce penalties against corrupt officials that break public procurement regulations or ask businesses for bribes;

- Refine and promote codes of conduct for officials in charge of public procurement, especially in the health sector;

- Develop guidelines on procurement processes for businesses and attach them in invitations for bid on the Vietnam National E-Procurement System;

- Make it mandatory for all invitations for bid to be publicly and timely released on the Vietnam Public Procurement Newspaper, the Vietnam National E-Procurement System, and portals of ministries and provinces to increase process transparency;

- Engage independent parties such as a professional association or a media outlet to oversee bidding activities;

- Conduct inspections, examinations and audits on public procurement agencies;

- Convene regular training, retraining, and education activities to improve capacity, awareness and ethical conduct for officials participating in public procurement; and,

- Promote and strengthen corporate governance standards and compliance for businesses both from the private and public sectors.-