Nguyen Hong Thao(*)

The new Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) opened for signature on September 20, 2017, and will enter into force in 90 days after getting 50 instruments of ratification. After one year, 19 ratification instruments were deposited, near one third of them from Asia-Pacific countries (including Thailand, Palau, Vietnam, New Zealand, Cook Island and Samoa).[1] This fact shows that Asia-Pacific is in the forward position to totally eliminate nuclear weapons in the world for the peace, security and human being. How to move forward the process of ratification of the TPNW? It’s is a big question before the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), other organizations and civil society to build a strategy to assist governments in achieving the final goal.

In order to clarify partly this question, the paper will focus on the three parts as follows: 1) Asia-Pacific and International Humanitarian Law; 2) Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons - a step towards the nuclear disarmament and 3) Ratification of the TPNW.

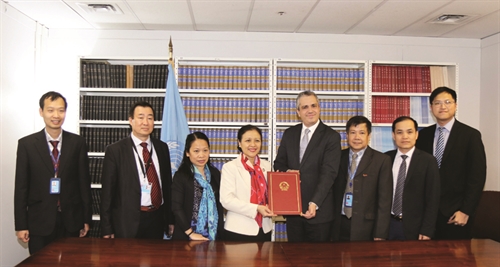

|

| On May 17, Ambassador Nguyen Phuong Nga, Permanent Representative of Vietnam to the United Nations, deposits with the UN Secretary General Vietnam’s instrument of ratification of the Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons__Photo: Huu Hoang/VNA |

Asia-Pacific and International Humanitarian Law

Asia-Pacific is the region that heavily suffered from mass destruction weapons. The first and unique nuclear attacks in 1945 killed about 140,000 people in Hiroshima, and a further 74,000 in Nagasaki.[2] The first widespread use of cluster munitions was in the Vietnam War period 1965-1975, during which American forces deployed roughly 800,000 cluster bombs.[3] In addition, 7.85 million tons of bombs were thrown over Vietnam, which was triple of the total bombs used by countries in the Second World War and compatible to the power of 250 nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima. The use of nuclear weapons, cluster munitions or land mines brought terrible unrecoverable consequences to civilians, goes straight against principles of international humanitarian law and the desire of human beings to live in a safe and clean environment.

Facing the challenges of ‘’war crimes”, international humanitarian law (IHL) has also arisen to punish those who use methods that unnecessarily increase the suffering caused by warfare.[4] With the huge effort of the ICRC, the world’s guardian of IHL, Asia-Pacific nations have made considerable contributions to the building, compliance and implementation of IHL. The Geneva Conventions adopted on 12 August, 1949[5] and the Additional Protocols of 1977 and 2005 supplementing to the Geneva Conventions[6] created a core of IHL. They imposed conventional obligations of ending the use of weapons that cause heavy sufferings to civilians in the wars. Those obligations own also the customary character and are binding even on non-parties to the Geneva Conventions. Any nation that has ratified the Geneva Conventions but not the Protocols is still bound by all provisions of the Conventions.[7] Article 35 of Protocol I prohibits to “employ weapons, projectiles and material and methods of warfare of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering,” It prohibits also “to employ methods or means of warfare that cause widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment”.[8] The basic rule of this article is that the right “to choose methods or means of warfare is not unlimited”. On the basis of this rule, new conventions on arms control have been developed such as 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), 1980 Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons, 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-personnel Mines, 2008 Cluster Munitions Convention, 2013 Arm Trade Convention, and 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Asia-Pacific has three among five nuclear weapons free zones in the world, except Antarctica and Outer Space: 1985 South Pacific Nuclear Weapons Free Zone Treaty (Treaty of Rarotonga), 1995 Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free-Zone (SEANWFZ) Treaty (Bangkok Treaty), and 2009 Treaty creating a zone free of nuclear weapons in Central Asia. Mongolia is Nuclear Weapons Free State. The other NWFZs are African and Latin America zones.

The Protocol to the Bangkok Treaty is open for signature by China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. These nuclear weapons states would undertake to respect the treaty and not to contribute to any act, which constitutes a violation of the Bangkok Treaty or its protocol by States Parties. They would also undertake not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against any State Party to the treaty and not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons within the SEANWFZ. Compared to other four NWFZ treaties, the Bangkok Treaty provides two additional elements: the zone of application also includes the continental shelves and EEZ of the contracting parties; and the negative security assurance implies a commitment by the nuclear weapons states not to use nuclear weapons against any contracting State or Protocol Party within the zone of application. This is the reason why some nuclear weapon states have not yet signed the Protocol.

On November 19, 2011, during the ASEAN Summit, ASEAN members and the nuclear-weapon states reached an agreement to pave the way for the nuclear powers to sign and ratify the updated protocol. This determination was confirmed by the Chairman’s statement on the 32nd ASEAN Summit in April 2018. ASEAN maintains its commitment to preserve the Southeast Asian region as a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone that is also free of all other weapons of mass destruction as enshrined in the SEANWFZ Treaty and the ASEAN Charter. ASEAN wants to continuously engage the Nuclear Weapon States (NWS) and intensify the on-going efforts of all Parties to resolve all outstanding issues in accordance with the objectives and principles of the SEANWFZ Treaty.[9]

In the final draft of a new convention on crimes against humanity that will be submitted to the General Assembly in 2019 for consideration, the International Law Commission (ILC) defines “crime against humanity” as “any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack....(k) Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health”.[10] The possession and use of nuclear weapons obviously will be considered a crime against humanity, and must be punished.

The campaign of ratification of the TPNW among Asia Pacific nations will make the treaty as soon as possible enter into force and serve as a basis for progress towards nuclear disarmament.

TPNW - a step towards the nuclear disarmament

The primary target of the humanity is to totally abolish nuclear weapons. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) stipulates the prohibitions on manufacturing and producing nuclear weapons. It emphasizes the objective to reduce and stop the arms race in the nuclear weapons field, but has no provision on the illegality of nuclear weapons. The 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty, CTBT) has provisions on the prohibition of nuclear tests, but has not entered into force because of the opposition of the six nuclear weapons states (China, North Korea, India, Israel, Pakistan and the United States) and two non-nuclear States (Egypt and Iran). The International Court of Justice in its advisory opinion on Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons in 1996 [11] accused that the threat by or use of nuclear weapons did not reconcile with the principles of international humanitarian law. However, at that moment, the Court did not have enough elements of fact to reach a definitive conclusion as to the legality or illegality of the use of nuclear weapons by a State in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which its very survival would be at stake.[12] While the two Conventions on mass destruction weapons, 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) and 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), have their own ban on the use of biological and chemical weapons, there is no explicit prohibition of use of nuclear weapons in the existing conventions, the NPT and CTBT. Since not all of nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaties contain a prohibition on development of nuclear weapons, this makes a big gap in the nuclear disarmament process. The TPNW fixes this shortcoming by banning the development, testing, producing, manufacturing, possessing, stockpiling, transferring and using or threatening to use of nuclear weapons. It also prohibits any activity to assist, encourage anyone to engage in any prohibited activity or to allow having, stationing, installation or deployment of any nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices in the territory of a State Party or at any place under its jurisdiction or control. The new treaty reaffirms that any use of nuclear weapons would be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflicts in particular, and to the principles and rules of international humanitarian law. The legally binding prohibition of nuclear weapons constitutes an important contribution towards the achievement and maintenance of a world free of nuclear weapons.[13] The new treaty is perfectly supplementary to the NPT. It’s one of effective measures relating to nuclear disarmament provided by Article VI of the NPT. It also confirms an “obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all of its aspects under strict and effective international control”.[14]

The Secretary General of the United Nations, António Guterres, in his new agenda for disarmament of 2018, said that: “The existential threat that nuclear weapons pose to humanity must motivate us to accomplish new and decisive action leading to their total elimination. We owe this to the Hibakusha- the survivors of nuclear war- and to our planet”.[15] To reach this aim, the ratification of the TPNW is a must.

|

| Ambassador Duong Chi Dung, Permanent Representative of Vietnam to the UN office in Geneva, at the second meeting of the Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons__Photo: Hoang Hoa/VNA |

Ratification of the TPNW

Asia-Pacific must set the priority goal to become a continent of prohibition of nuclear weapons. To achieve this goal, some measures could be envisaged and implemented.

The first measure is to mobilize countries that have consistently pursued the nuclear weapons free policy to ratify the TPNW. Thailand is the first country to ratify the TPNW right on the day of opening for signature on September 20, 2017. The reason is simple because Thailand is the host country of the SEANWFZ Treaty. New Zealand ratified it on July 31, 2018 to pursue its “long-standing commitment to international nuclear disarmament efforts”.[16] Palau, a small island country, which ratified the TPNW on May 3, 2018, is the first country in the world that approved the nuclear-free constitution[17] in 1981.[18]

Vietnam, the country submitting a ratification instrument to the United Nation on May 17, 2018, became the tenth in the list of ratification of the TPNW.[19] It’s interesting to remind that Vietnam ratified all three nuclear weapons free conventions, the NPT in 1982 and the CTBT in 2006 and the TPNW in 2018. The provisions of the TPNW are compatible with Vietnamese laws and regulations in this field. Article 12 of the Vietnamese Law on Nuclear Energy[20] and Articles 1, 4 and 27 of the Law on National Defense enumerate almost prohibited acts of nuclear weapons use listed in Article 1 of the TPNW. The ratification of the TPNW demonstrated Vietnam’s commitment enshrined in its National Defense White Paper of 2009[21] that “Vietnam supports any initiative to prevent the development, manufacture, stockpiling and use of mass destruction weapons.”

The second step is to encourage States to conclude with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) a comprehensive safeguards agreement before and in parallel with the process of accession to the TPNW. Articles 2 and 3 of the TPNW stipulate the obligations of States to have a declaration on the possession of any nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices in its territory or the installation of nuclear weapons and other nuclear explosive devices of foreign States in any place under its jurisdiction or control. States must conclude and implement comprehensive safeguards agreements with the IAEA. Countries which have good cooperation with the IAEA are easy to accept ratification of the treaty. Vietnam case is a typical example. Vietnam signed a similar agreement with the IAEA in 1990 and has fulfilled well its obligation on declaration and transparency on nuclear use. Article 4 of the TPNW will not cause any difficulty to Vietnam, which consistently maintains its three-no policy including non-allowing any foreign country to use its territory against other third country. In August 2007, Vietnam signed the Additional Protocol to the safeguards agreement with the IAEA to meet any requirement of supervision over nuclear reactors and of highest standards of the IAEA.

The third measure is to clarify the benefits of ratification of the TPNW to developing countries. The TPNW does not demand any financial expense from developing countries that own no nuclear weapons. Developing countries do not have to bear the cost of destruction or supervision of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, owned by nuclear States (Article 9.3). State Parties only bear the costs of the meetings of States Parties, the review conferences (in 6 years) and the extraordinary meetings of States Parties, and the costs incurred by the Secretary-General of the United Nations in the circulation of declarations under Article 2, reports under Article 4 and proposed amendments under Article 10 of this Treaty in accordance with the United Nations scale of assessment adjusted appropriately (Article 9.1 and 9.2). These costs are not significant. On the contrary, the TPNW respects the independence, sovereignty and impeccable territory of States Parties, the non-interference into their internal affairs, the equitable and mutual benefits as well as the settlement of disputes by peaceful means (Article 11.1). It confirms that “nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of its States Parties to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination” (Preamble). The treaty also stipulates the possibility of withdrawal for a State Party if “it decides that extraordinary events related to the subject matter of the Treaty have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country” (Article. 17.1). Those provisions assure favorable conditions for non-nuclear weapons developing countries in using nuclear energy for the purpose of peace and social-economic development. Non-nuclear weapons developing countries have the right to require States using nuclear weapons to bear responsibility in “adequately providing age- and gender-sensitive assistance, without discrimination, including medical care, rehabilitation and psychological support, as well as provide for their social and economic inclusion”. They can require the measures to remedy contaminated areas (Article 6). They also have the right to seek and receive assistance, where feasible, from other States Parties (Article 7.2).

The more ratifications from developing countries will put the more pressure on nuclear weapon States. However, the final goal to totally eliminate the nuclear arsenal in the world cannot be achieved without the active participation of nuclear puissance in the TBNW. To attain the more participation of nuclear weapon States, the TPNW furnishes provisions on general obligations of States Parties in declaration (Article 2), safeguard measures (Article 3), and cooperation towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons (Article 4). Moreover, it makes no detailed provisions on the procedure, rights and obligations, treatment and enforcement measures. Each State Party shall adopt the necessary measures to implement its obligations under the TPNW (Article 5.1). Each State Party shall take all appropriate legal, administrative and other measures, including imposition of penal sanctions, to prevent and suppress any activity prohibited to a State Party under the TPNW undertaken by persons or on territory under its jurisdiction or control (Article 5.2). It allows States, particularly nuclear weapon States to consider their own security interest in taking appropriate measures towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons, including the ratification of the TPNW. Nuclear weapon States have time to put forth concrete proposals on disarmament measures before joining and have plan to implement disarmament after accession to the TPNW. The “join then disarm” approach can help reduce the tension between nuclear weapon States and others. The first goal is “get NWS to the negotiation table”. The ICRC and other NGOs can assist concerned governments to review with a view to amending and enacting domestic legal acts in conformity with the TPNW. In case of Vietnam, some safeguard measures (Article 3) of the TPNW have been applied directly because they are in accordance with the Law on Nuclear Energy and Agreement on safeguards and Additional Protocol to the Agreement concluded by Vietnam and the IAEA.

Finally, governments, NGOs and civil society across the world must make urgent pressure to the threat from the emergence of new nuclear states and reduce the number of existing nuclear States through the TPNW, international humanitarian law and diplomacy.

Together, hand by hand, States and international organizations, including the ICRC, will stop the use of nuclear weapons to save our planet for humankind, generations to generations.-

[1] https://www.icanw.org/status-of-the-treaty-on-the-prohibition-of-nuclear-weapons/, accessed 01 October 2018.