Dang Ngoc Ha, Ph.D.[1] and Tran Hong Nhung LL.D.[2]

|

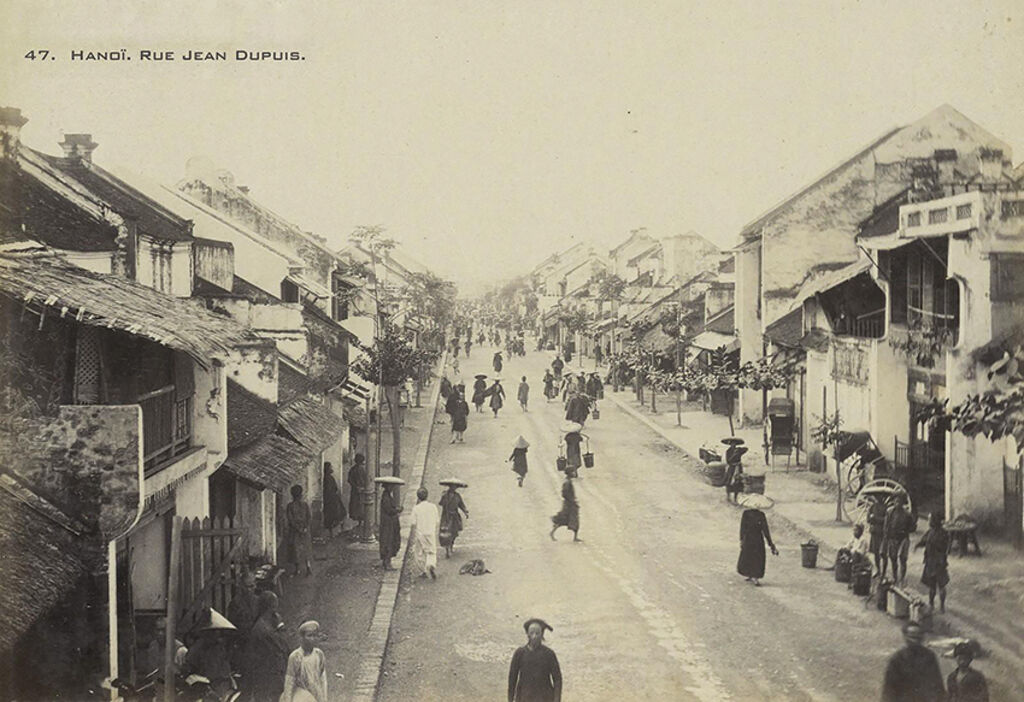

| Rue Jean Dupuis, now Hang Chieu Street, in late 19th century__Photo: humazur.univ-cotedazur.fr |

Vietnamese cities in medieval times were characterized by distinctive features compared to those in the region and the world, with the “do” (urbanity) character prevailing over the “thi” (business) character, and the “nong” (agricultural) character prevailing over the “thuong” (commercial) character. These features influenced the ways of urban management by various Vietnamese dynasties. This article focuses solely on the organization and management of Thang Long-Hanoi, the most ancient and largest city of Vietnam during medieval times.

Administrative planning

The medieval history of Thang Long-Hanoi can be traced back to the time King Ly Cong Uan moved the royal city from Hoa Lu (in present-day Ninh Binh province) to Dai La (of Hanoi) and named it “Thang Long” (Flying Dragon) in 1010, until the French colonialists invaded the country in the late 19th century, spanning nearly nine centuries. The research by Associate Professor Dr. Vu Van Quan and Master Le Minh Hanh into “the administrative planning and the organization of Thang Long-Hanoi management machinery in medieval times[3] summarized the important features in the administrative planning of Thang Long- Hanoi during the feudal period as follows:

First, during the pre-19th century period, Thang Long-Dong Kinh, as the royal capital, was a special administrative zone directly governed by the central administration. Obviously, due to its position, role and function, various monarchies applied a special mechanism of administrative decentralization to the royal city.

Second, in the initial administrative structure (under the Ly and Tran dynasties), the city was structured with only two levels: “phu” (town) and “phuong” (urban district). From the Early Le dynasty on, it was organized with three levels: “phu”, “huyen” (rural district), and “phuong”, similar to rural areas. When the rural structure was added with the “tong” level to make four administrative units, the royal city still retained the three-level administrative system, thus demonstrating its distinction from other localities.

Third, throughout medieval times, as the royal city, Thang Long’s administrative territory remained largely unchanged. It was located in the heart of the present-day Hanoi, with 36 craft guilds, two “huyen”, and one “phu”. The stability of the administrative territory of the royal city brought about favorable conditions for management, while shaping and stabilizing the identity of Thang Long in various aspects, especially culture.

It can be observed that over nearly 850 years, under various dynasties - Ly, Tran, Early Le and Mac, Thang Long was the political, economic and cultural center of the whole country where the royal court sat, being the “face of the nation”. Its population was diverse in social strata, economic activities, social relations and prominent position; hence, the management of this city was complex, with many distinctive characteristics. Although small in terms of area and population, Thang Long was considered a special administrative unit on an equal footing with the highest local administrative units. This served as a basis for feudal states to organize different units within the management apparatus and to appoint a chief of Thang Long administration.

Administration apparatus

As the political and administrative center of the country, Thang Long-Hanoi during the monarchical period was the seat of the royal court, including kings and mandarins. In such circumstance, Thang Long was placed under the intertwined management of both the central administration apparatus and the local administration apparatus across all aspects of urban life. This governance followed a hierarchical structure, from higher to lower levels (from city to district, and then ward - the grassroots administrative level). However, the biggest difference was that the control of the central administration over the capital city, whether direct or through the local administration, was more concentrated in space compared to other localities nationwide, thus resulting in extremely high effect. The local management apparatus in the capital city served both the direct manager and coordinator with the central administration in performing state management.

The local administration system in the capital city corresponded to a subordinate level as “lo, dao, tran, su”, but was placed under the direct management of the central administration. Before the formation of the “tong” level, the system was composed of three levels: “phu”, “huyen” and “phuong”.

According to historical records, the chiefs of these administrative units were carefully selected, with higher ranks and more clearly defined responsibilities than mandarins in other localities. For example, under King Le Thanh Tong’s reign, the capital city was headed by “phu doan” (governor of the province where the capital was located), with the assistance of “thieu doan”. In 1510, “de linh” (martial mandarin) was appointed directly by the royal court to take charge of security in the capital city.

Under the Early Le dynasty, two districts of the capital city were headed by two mandarins called “huyen uy”, assisted by “thong phan”. Meanwhile, districts in other localities were headed by “tri huyen” assisted by “huyen thua”.

With the establishment of a tidy and small but highly effective administrative apparatus, the feudal states placed great importance on the appointment of mandarins to head the Thang Long-Hanoi administration and its subordinate units for the effective management of the city.[4]

|

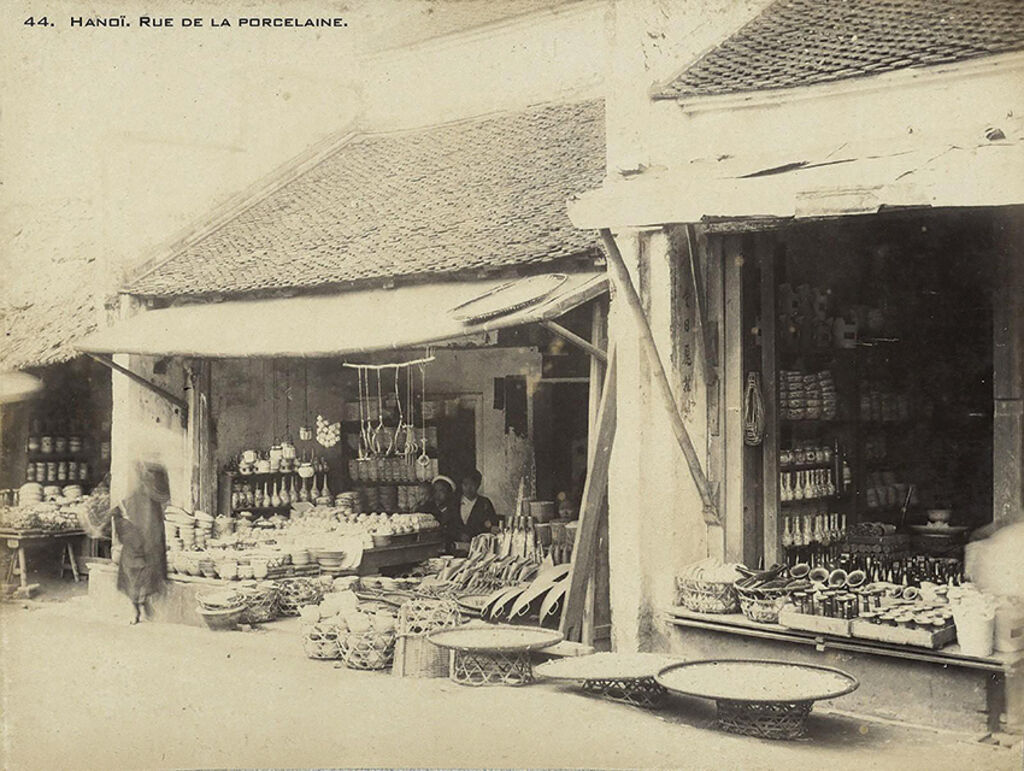

| Rue de la Porcelaine, now Hang Dong and Bat Su Streets__Photo: humazur.univ-cotedazur.fr |

Management of Thang Long-Hanoi city in various aspects

Population management

From the 15th to the 18th century, Thang Long was the largest and most prominent city, inhabited by a diverse population from all walks of life. There is no official statistical data on Thang Long’s population during this period. Yet, according estimates by Western preachers and merchants at the time, “the population of this crowded city may reach one million people”, with “about 20,000 houses”, surpassing even large European cities in “activity and population”. Visitors unanimously felt that “Ke Cho” (the ancient name of Thang Long-Hanoi) was the most populated city in then Vietnam and one of the highly populated cities in Asia and the world.

Given this reality, the management of population, especially immigration, became an urgent requirement for local administrations at all levels. At the end of the 14th century when people from different regions rushed into the capital city to earn a living, the Phu doan (chief) of Phung Thien town ordered all migrants to be expelled back to their native places. Realizing this was not the optimal measure, Quach Dinh Bao, deputy chief of “Ngu Su Dai” (the office in charge of personnel affairs and judicial judgment), filed a report to the royal court for reconsideration. He proposed allowing those with shops already registered for taxation to stay for business activities while expelling all jobless migrants.

In a decree promulgated in 1484, King Le Thanh Tong ordered: “People around the capital city who are honest and wish to stay in the capital will be permitted. Those who act against this order shall be sentenced to exile (Hong Duc thien chinh thu, pp. 294-295). Thus, the feudal state implemented a policy permitting and creating conditions for people to move to the capital city to lawful live and earn a living.

However, the State also applied various policies to strictly control immigration into Thang Long. Addressing the situation where soldiers recruited from various localities in the capital city were too numerous, causing disorder and insecurity, Trinh Lord ordered in 1740 that these units stay outside the capital city and not live among civilians. In 1777, Trinh Lord issued a decree requesting “de linh” (martial mandarin) to intensify control and inspection of all quarters and palaces, expelling those who had neither tasks nor household registration from the capital city. For foreigners, the Le-Trinh feudal state implemented stricter policies, banning them from staying with local people in the capital city.

Management of economic activities

Under the Early Le dynasty, there were almost no state laws on the management of economic activities in Thang Long. In “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” (The National Royal Criminal Code), only Article 82 stated: “In the royal city, craftsmen and traders are not allowed to open shops; those who act against this order will be punished with 50 truong (heavy wood stick), or one-rank demotion, for violating mandarins, a fine of 10 quan (an ancient currency unit) for subjects unaware of the law, or 30 quan, for tolerating mandarins”. However, such a ban aimed mainly to maintain security and order in the capital city, and was less related to managing economic activities.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, Thang Long, with its vigorous development, became the most prosperous industrial and commercial city. The growth of specialized handicraft villages, the formation of regional and inter-regional markets, and the promotion of foreign trade created an economic picture of Thang Long with more dynamic and busier activities than in any other locality or previous period. Naturally, this required the expansion and refinement of the management system, primarily the legal system.

Due to its distinctive feature and important role, Thang Long-Ke Cho developed beyond the framework of management by local administration and came under strong control of the central feudal state. In the capital, craft guilds and market networks were managed by local administrations, which were less prominent than those in rural localities, and also under the direct control of the feudal state.

First of all, the feudal state managed trade activities in Thang Long through regulations on market establishment. Under law, “markets are places for the circulation of goods among the population, promoting goods exchanges to satisfy people’s demands. Thereby, the State set the system of organizing market sessions according to cycle, aiming to administer the entire market system. Villages, communes or hamlets that fail to abide by this system will be severely punished” (Hong Duc Thien Chinh Thu, p. 492).

To enhance its capacity to control trade activities in the capital city, in 1740, the State established the position of “market price stability mandarin” to monitor money circulation. “Each market selects a market chief (or market supervisor) to carefully examine lawful currency or counterfeit before permitting the trading.” The state law strictly prohibited market chiefs, market supervisors and traders from acting against the regulation. Article 576 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat stated: “Traders in markets, market supervisors who break the law will be penalized with biem (demotion) or do (hard labor)”.

For business people in the capital city, the central administration applied policies to encourage and create conditions for them, and protect their interests. Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat stated: “Market supervisors in the capital city who harass for bribes shall be punished with 50 lashes, demotion by one or two ranks for collecting heavy market taxes, dismissal, and compensation for people. The fine money would be rewarded to denouncers according to regulations. If collecting market taxes illegally, they would be punished with 80 truong and exposed to shame in the market for three days (Article 186).

In a decree promulgated in December 1634, Trinh Lord ordered: “Markets are established for goods circulation, facilitating trading and consumption. From now on, influential people and yamen must stop sending agents to the markets to harass traders for money. Those who disobey the order shall be questioned or arrested together with material evidences and sentenced for grave crimes”. In 1647, Trinh Lord repeated in an order on a royal ceremony: “The capital city is a civilized land and a hub of commerce, with people and traders bringing goods to the capital markets. Yamen are strictly forbidden to levy money on the markets so that people can do business with ease”.

The central feudal administration’s management of Thang Long capital also included regulations related to foreign trade. In 1650, Trinh Lord decreed that foreign merchant ships from France, the Netherlands, Japan and China were not allowed to enter Thang Long. They had to stop at harbors and dispatched people to the capital asking for permission. If approved by the royal court, the captains and crewmembers would stay at the two locations near the capital, namely Thanh Tri and Khuyen Luong (or Yen Thuong station). For visitors coming from the North, the state appointed officials to manage them and act as interpreters (Quoc Trieu Chieu Lenh Thien Chinh, pp. 580-81). “When arriving at the capital city, they must comply with strict regulations of the administration; must not enter restricted areas, compel people to sell their goods, clandestinely exchange valuable commodities reserved for kings or lords, or trade goods banned by the state.”

The above-mentioned policies of the feudal state aimed to strictly control all economic activities in the capital. Though such control had positive impacts, especially over foreign trade, it resulted in certain limitations on the process of urbanization in Thang Long during medieval times.

Management of security and order

To ensure security and order for the city, Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat prescribed the responsibilities of mandarins at towns, rural districts, wards and communes. Article 458 of the Chapter on robbers and thieves stated: “If robberies take place in wards or alleys in the capital city, and ward mandarins do not send men to the rescue and arrest criminals, they shall be sentenced to do (hard labor); ward inhabitants or soldiers who do not come to the rescue shall be penalized with truong or biem. If mandarins in nearby wards did not join force to fight robbers, they shall be subject to the same penalties”. Article 329 clearly stated: “If martial mandarins in the city fail to organize night patrols by soldiers, they shall be punished with 60 truong. If robbery or gambling occurs in their wards and they do not report it to mandarins for punishment, they shall be sentenced to biem or do”. The responsibilities and tasks of ward chiefs were further specified in subsequent decrees.

Management of cultural and social activities

The feudal state also attached importance to the management of cultural and social activities. The maintenance of customs and practices, and the ban on gambling and drinking, were clearly defined in law. When entering the kings’ or lords’ palaces, people must not sing noisily. If not, they would be punished with 50 whippings, and their musical instruments would be burned (Article 9 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat). In royal palaces, if they behave impolitely, they would be sentenced to biem or do (Article 46). Those who let funeral processions pass through the four gates of the royal city would be punished with 50 whippings and demoted one rank (Article 49). One month before and after the kings were crowned, people in the capital city were forbidden to organize funerals. Violators would be punished with 50 lashes and a one-rank demotion (Article 40).

With the prerequisites created thousands of years earlier, by the 11th century Thang Long became the political, economic, social and cultural center of sovereign Dai Viet (former name of Vietnam). Throughout the medieval times, Thang Long was also the largest, most prominent and almost unique city of Vietnam. The system of state law on urban management was devoted first and primarily to Thang Long. A large number of legal provisions regarding Thang Long reflect its magnitude, position and special role, and also reveal the necessity and complexity of managing this city. Due to its peculiarity, the capital city witnessed the existence of two systems: central and local administrations. In addition to these separate management institutions, Thang Long was also subject to the strict control and governance of the state administration. Clearly, there existed a system of law on management of all aspects of life in the capital city.

Besides its undeniable positive impacts, the central administration’s management policies applicable to Thang Long revealed certain limitations, which inadvertently hindered the development of the capital city. New aspects of Thang Long emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries. Yet, due to the lack of decisive breakthroughs and the strict management policies of the Confucian monarchies, Thang Long was unable to strongly develop and advance. The development of social life requires new management models to replace the old ones.-

[1] Dang Ngoc Ha, Ph.D.

Institute of Vietnamese Studies and Development Science

Vietnam National University, Hanoi

[2] Tran Hong Nhung LL.D.

Administration-State Law Faculty

Hanoi Law University

[3] http//Hanoi,vietnamplus.vn/Home/Quy hoach-to-chuc-bo-may-Thang-Long-thoi-trung-dai/20121/8459.vnplus.

[4] Associate Professor, Doctor Bui Xuan Dinh and Ta Thi Tam in the article “Position and apparatus of Thang Long- Hanoi administration in the administrative system of feudal Dai Viet (1010-1888). Source: http://tuyengiao.vn/thanglonghanoi/thanglonghanoi/vi-the-va-bo-may-chinh-quyen-thang-long-ha-noi-trong-he-thong-hanh-chinh-nuoc-dai-viet-thoi-phong-kien-1010-1888-24367.