Ly Tung Hieu

PhD. in Philology

Ho Chi Minh City National University of Social Sciences and Humanities

|

| Buoi market in Hanoi in old times__Photo: https://baotanglichsu.vn/ |

Vietnamese entrepreneurs constitute a social group with a long history, distinctive traditions and valuable contributions, which has played a pivotal role in different periods of the country’s socio-economic prosperity. This writing outlines the formation and development of this group across a long historical period, commencing from the Chinese domination that began in 111 B.C. marked by Supreme Commander Lu Baide’s conquest and annexation of Nam Viet (former name of Vietnam) and ended in the year 938 A.D. when Ngo Quyen triumphed over the invading forces, reclaiming national independence and sovereignty, until the country’s loss of sovereignty to the French colonialists under the 1883 Peace Treaty.

Vietnamese entrepreneurs during the northern domination period

The formation of the Hoa (Chinese) entrepreneur group

In the Chinese domination period, the Chinese culture influenced the Vietnamese culture extensively and intensively. In 106 B.C., the Han dynasty established Giao Chi Bo (ancient Vietnam), ruling seven districts (including Guangdong, Guangxi and present-day northern Vietnam). In couple with the process of forced assimilation by the invading administration was the process of natural assimilation of Chinese mandarins, soldiers and migrants in Giao Chi Bo- Giao Chau. The cultural baggage brought by Chinese migrants comprised new trades (small industries, handicrafts, trade, and farming), culinary culture, clothing styles, ways of living, means of transport, and religions, including Buddhism and Taoism.

Chinese culture prevailed in administrative centers and citadels at different administrative levels. They encompassed Me Linh capital, which served as the headquarters of Giao Chi district from 106 B.C. to 40 A.D., and as the capital city of the Trung Sisters’ rule from 40 to 43 A.D., in Me Linh commune, Me Linh district of present-day Hanoi, then Long Bien as the administrative headquarters of Giao Chi district and Giao Chau province from 264 to 542 A.D., and the capital city of Van Xuan kingdom from 550 to 571 A.D. in the region of Tien Son, Yen Phong, present-day Bac Ninh province. Later, Tong Binh-Dai La served as the administrative headquarters of Giao Chi district from 607 A.D., and as An Nam headquarters from 725 to 866 A.D., then renamed as Dai La, the capital of Tinh Hai Quan from 866 to 938 A.D., which is located in the heart of present-day Hanoi.

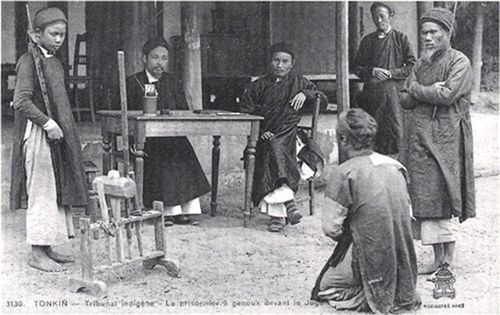

Living inside such centers and citadels were mandarins, army generals, officers and soldiers and their families, who were no longer engaged in production activities. As a result, various handicraft and commercial streets quickly mushroomed around these centers to supply goods, both luxurious and essential, for the occupying forces. Hence, a class of traders, workshop owners and artisans emerged, with Chinese migrants as the core. Together with invading mandarins and army men, those traders, workshop owners and artisans of Chinese origin directly formed the first type of Vietnamese urban centers which included workshop areas and market streets dependent on the administrative headquarters and citadels.

In addition to their role as goods distributors for domestic markets, Chinese-origin traders controlled foreign trade activities which developed vigorously during the northern domination period thanks to abundant sources of export products in Giao Chi Bo-Giao Chau, such as elephant tusks, rhino horns, tortoise shells, pearl, coral, especially aquilaria, cotton cloth, silk, paper, cane sugar, glass articles, etc. All these trading activities were dominated by Chinese traders and rulers.

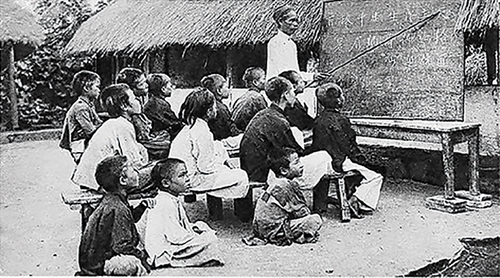

The birth of local entrepreneurs

Despite foreign invaders’ attacks, massacres, destructions and looting, the economy of Giao Chi Bo-Giao Chau continued to develop thanks to the enduring traditions from Van Lang-Au Lac era and the imported achievements of Chinese culture. According to various historical and archaeological records, during this prolonged foreign domination, the Viet Muong (ancient Vietnamese) people developed such handicrafts as bronze casting, iron forging, textile, sugar production, paper making, glass making, fine-art article production, salt processing, and liquor distillation. The Vietnamese craftmen possessed good and renowned skills that the feudal Chinese administrator of Giao Chi district, known as Sun Xiu, compelled more than 1.000 local craft men to work in the capital city of Wu kingdom, now the city of Nanjing, China.

The Viet Muong’s handicrafts developed thanks to trade exchanges between Giao Chau and foreign lands. A number of Vietnamese handicraft articles were exported, and various foreign techniques were imported. This exchange gave rise to a group of local entrepreneurs, who helped connect local workshop owners with Chinese and foreign traders. These were the first local entrepreneurs in the history of Vietnamese economy, who would play a more significant role in the national economy of Dai Co Viet-Dai Viet (ancient Vietnam) in the subsequent years.

Vietnamese entrepreneurs in the feudal period

The development of Chinese and Minh Huong entrepreneurs

In feudal Vietnam, Chinese traders still played a key role in the economy, especially foreign trade, owing to their good relations with foreign merchants and markets. First, they participated in economic activities of Thang Long (present-day central Hanoi).

In 1035, King Ly Thai Tong opened a market of Tay Nhai to the west of the Thang Long royal city, which is now Ngoc Ha market in Doi Can ward, Ba Dinh district. This market quickly became a busy venue for Chinese and Vietnamese traders to supply essential and luxury goods for commoners, aristocrats and mandarins in the royal city.

In 1407, Chinese Ming troops invaded Dai Viet and occupied the country till 1428. During this time, “Hanoi with thirty six streets and guilds” was formed on Thang Long’s outskirts, with Chinese workshop owners and traders playing a crucial role as suppliers of consumer goods for the occupying troops. After Dai Viet regained independence and sovereignty, Chinese workshop owners and traders stayed on the streets in the vicinity of Thang Long until the French colonialists conquered the country. Along with Vietnamese traders, Chinese workshop owners and traders continued participating in the development of “thanh thi” (urban centers), the initial form of Vietnamese cities.

From the 17th to 18th century, together with Vietnamese and foreign traders, Chinese entrepreneurs contributed to the formation of second-typed urban centers in Vietnamese history: self-reliant industrial-commercial towns. To make full use of foreign resources, various kingdoms of Dai Viet applied the open-door policy for trade exchanges, which resulted in the establishment of a series of industrial-commercial towns, each composed of craft workshops, warehouses, markets, ports and residential quarters. Usually located along the waterways to facilitate trade with domestic markets and connect the domestic markets with foreign countries, these industrial-commercial cities were also port cities. With their own sources of raw materials, production and business establishments and outlets, they became self-reliant economic hubs, without relying on mandarins, army officers and soldiers and their families living in administrative headquarters and citadels.

From 1149, when King Ly Anh Tong founded Van Don commercial port in Quang Ninh province, Chinese traders together with merchants from Indonesia, Thailand, Japan, China and India turned this first commercial port of Dai Viet into one of the busiest ports until the 18th century.

During Manchu’s conquest of China (1644-1682), Chinese people fled to northern Vietnam and conducted their business there. They joined traders from China, the Netherlands, Japan, Thailand, England, France, etc., in making Pho Hien (present-day Hung Yen city) a prosperous inland port only second to the Thang Long royal city. Meanwhile, the Chinese fleeing to southern Vietnam joined traders from China, Portugal, Japan, England, France, etc., in turning Chiem Cang into a prosperous port in Hoi An (now Hoi An city of Quang Nam province). In 1679 Lord Nguyen Phuc Tan ordered two generals, Duong Ngan Nghich and Tran Thuong Xuyen, led 3,000 soldiers to Cochin-China for land reclamation and settlement. General Tran Thuong Xuyen and his men set up Nong Nai Dai Pho (Pho islet, Bien Hoa city of present-day Dong Nai) and Sai Gon market. Meanwhile, Duong Ngan Nghich took his men to My Tho, building houses and establishing My Tho Dai Pho (Ward 2 area, My Tho city of present-day Tien Giang). In 1680, a trader named Mac Cuu mobilized local inhabitants to establish seven communes from Vung Thom to Ca Mau. Prominent among the residential area set up by Mac Cuu and his offspring was Ha Tien port (Ha Tien city of present-day Kien Giang).

In 1698 when Gia Dinh district was established, Nguyen Huu Canh allowed Chinese people in Tran Bien to set up Thanh Ha commune and Minh Huong commune in Phien Tran. In 1834, King Minh Menh classified Chinese migrants into two groups: Minh Huong (Vietnamese people of Chinese origin) were organized into Vietnamese-style villages and communes, while Qing Chinese were organized into communities according to their original traditions.

In their native place of China, Chinese people practiced various occupations to earn their living. But after migrating to Vietnam, they selected occupations of their cultural advantage: handicraft, trade and services. Chinese entrepreneurs in Vietnam often enjoyed the assistance of Chinese traders at home and in Southeast Asia. They also benefited from the support policies of Vietnamese kings and lords. Their successful economic activities helped change the Vietnamese idea of highly treasuring farmers while looking down upon traders, and boosted the process of urbanization in Sai Gon-Cho Lon area and other southern localities. Over time, children and grand-children of Chinese entrepreneurs were gradually assimilated into Vietnamese society. Vietnamese craft men and traders learned techniques, handicraft and trade secrets of Chinese people, heightening their occupational skills. Thereby, the Vietnamese entrepreneur group developed during the feudal time.

The development of Vietnamese entrepreneurs

During feudal Vietnam, rice growers in northern and north-central deltas spent their free time to make handicrafts. Initially, they opened handicraft workshops such as pottery and brick kilns and bronze casting and weaving workshops. Later, they developed into craft villages such as Chu Dau pottery village (Hai Duong province), Bat Trang pottery village (Hanoi), Dinh Cong silver and gold jewelry village (Hoang Mai district of Hanoi), Ngu Xa bronze casting village (Ba Dinh district of Hanoi), Ke Buoi paper-making village (Tay Ho district of Hanoi), Van Phuc silk weaving village (Ha Dong district of Hanoi, Dong Ky fire-cracker making village (Bac Ninh province), etc. It was due to their prosperous production and trading activities, Thang Long was called as “Ke Cho” (urban market) .

Through the southward migration, handicrafts and trade were brought and developed in southern Vietnam, where famous craft villages emerged. They include Kim Bong carpentry village in Hoi An, Phuoc Tich pottery village and My Xuyen wood carving village in Thua Thien- Hue; Phuong Duc and Thuy Xuan bronze casting villages in Hue royal city, Phuoc Kien bronze casting village in Quang Nam province, to name a few.

By the end of the 17th century, Vietnamese entrepreneurs joined Chinese traders in establishing major trade centers throughout Gia Dinh region. Agricultural, fishery, handicraft and other types of products were transported from production areas to markets or commercial ports.

In summary, Vietnamese entrepreneurs have a long history, distinctive traditions and valuable contributions to the socio-economic prosperity in the country. Yet, this social group was weakened under the Nguyen dynasty due to the feudal rulers’ bias against entrepreneurs and erroneous economic policies in the 19th century. The national economy then also declined because the Vietnamese entrepreneurs were not given favorable conditions for development and their socio-economic role was not properly appreciated. This may serve as a good lesson for us in the current socio-economic development period.-

References:

(1) Hoang Phe, Vietnamese dictionary, Hong Duc publishing house.

(2) Phan Huy Le, Tran Quoc Vuong, Ha Van Tan, Luong Ninh (1983), Vietnamese history, vol. 1, University and Intermediate-level Professional Education publishing house, Hanoi.

(3) Do Duc Hung, Nguyen Duc Nhue, Tran Thi Vinh, Truong Thi Yen (2001): Vietnam and Historical Events (from the initial stage to 1858), Education publishing house.

(4) Ngo Vinh Chinh, Vuong Mien Quy (1994), Fundamentals of Chinese culture history, Culture-Information publishing house, Hanoi.

(5) Trinh Hoai Duc, Gia Dinh Thanh thong chi (Gia Dinh’s chronicles), Education publishing house.

(6) Nguyen Cam Thuy (2000), Chinese people’s settlement in southern land (from the 17th century to 1945), Social Sciences publishing house, Hanoi.

(7) Le Quy Don (2007), Phu bien tap luc (miscellaneous writings), Culture-Information publishing house, Hanoi.