Tran Hong Nhung LL.D.

State Administrative Law Faculty

Hanoi Law University

Overview

The self-rule or autonomy regime was an outcome of peculiar historical and socio-economic conditions of the Vietnamese villages during the feudal time. The closed, self-sufficient economic status in every village led to its social isolation. In addition, the self-rule tradition was the consequence of over a millenium year-domination of the northern feudalists, with Vietnamese clustered in villages and communes to keep in status quo their native cultural values, thus turning the then Vietnamese villages into green fortresses against the assimilation and enslavement by the northern feudalists. From the 9th to 19th centuries, Vietnamese dynasties applied different administrative measures to enhance their control over the rural areas but still recognized and respected the village self-rule and autonomous tradition. Such behavior of the Vietnamese feudalists constituted one of the decisive factors for the success or failure of the royal court in its village management policies.

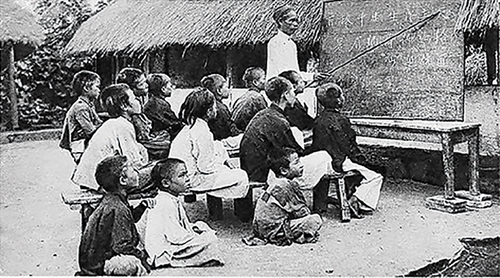

Studies reveal that unlike Chinese and Southeast Asian villages during feudal time, the Vietnamese villages and communes applied a stricter self-rule regime[1] with a fairly large scope covering various aspects of the community life, such as production organization (primarily irrigation), relations between different social strata, security protection, management of public property, public land division, learning promotion, social relief, organization of cultural and spiritual activities, and the implementation of tax and conscription duties. Villages specified and detailed provisions of national laws into regulations of their respective village conventions. The feudal states permitted villages to organize by themselves their own management apparatuses, including the election of village and commune chiefs (during King Le Thanh Tong’s tenure, and respected traditional management institutions, etc.). Villages were allowed to compile their own conventions, which were recognized by the royal court as their own codes existing in parallel with, and as a part of, the state law.

|

| A market in Hung Yen province during the feudal time__Photo: https://hinhanhvietnam.com/ |

| A market in Hung Yen province during the feudal time__Photo: https://hinhanhvietnam.com/ |

Specific regulations on village self-rule regime

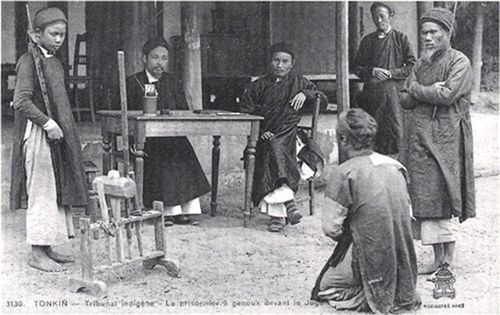

Firstly, regulations on election of village headmen: The 1462 decree during King Le Thanh Tong’s rule (1460-97) stated: “To elect persons of the right ages or honest students aged 30 or over. Village headmen must be literate and possess good virtues in order to well handle village affairs, including tax collection. Election of improper persons constitutes a crime”. In the reform of village administrative apparatus advocated by King Minh Menh (1820-40), the State set out a number of regulations in order to standardize village headmen who “must possess a given quantity of assets, must be industrious”. During the Nguyen dynasty, the State officially recognized the autonomy mechanism in the organization of village management apparatus. The self-rule apparatus, called “Hoi Dong Ky Muc”[2] (the Council of village elders), was composed of elders who were not elected by people but satisfied the conditions prescribed by “huong uoc” (village conventions). According to “Hong Duc thien chinh thu” (a historical book), King Le Thanh Tong provided: “Villages can have their own conventions to get rid of evil customs and practices, which can be enforced if they are compiled by knowledgeable, virtuous and elder persons. The elaborated conventions must be submitted to superior mandarins for consideration and approval”[3]. So, village customs and practices were officially recognized by the State but on the principle that they would not run counter to the state laws. Such provisions created a legal corridor for the village self-rule regime during the feudal time.

Secondly, clear definition of the organizational structure, functions and competence of headmen of local self-rule units, and development of administration models suitable to the characteristics of each locality: Under the Nguyen dynasty, village chiefs held the commune-level administrative powers with the following responsibilities:

To manage the village land on behalf of the State.To strictly manage the village commoners and household registration on behalf of the State.To urge the full collection of land tax and poll tax as scheduled.To urge villagers to fulfill the conscription and public labor obligations toward the State.To be responsible for all village affairs such as the maintenance of village order and security, the organization and management of road repair, irrigation work, etc.Between two village self-rule institutions, namely “Hoi Dong Sac Muc” (the Council of village dignitaries) and “Hoi Dong Ky Muc”, existed the clear-cut definition of functions. “Hoi Dong Ky Muc” resolved, worked out orientations and solutions to settle administrative issues promulgated to villages and communes by the State while “Hoi Dong Sac Muc” acted like the executive body to manage, enforce and abide by the resolutions of “Hoi Dong Ky Muc”. The clear-cut definition of functions, tasks and powers in the village management institution in the feudal time helped prevent the abuse of powers by village mandarins and oversee the administrative institution, on the one hand, and assisted the State in promoting the positive aspects of the village self-rule institution, on the other hand.

The feudal village autonomy model applied on the principle that what the village administration could do, the superior administration would not intervene, and what the village administration could not perform, the superior administration would provide assistance. The village administration constituted the level closest to the people and directly performed the essential and basic public services for individuals. So, specific tasks and powers were listed for the village administration to perform the self-rule tasks.

|

| Hanoi’s Hue street in the 19th century__Photo: https://hinhanhvietnam.com/ |

Thirdly, the village self-rule organizational structure varied from village to village, depending on their size.

According to King Le Thanh Tong’s 1483 decree, communes were classified as large with 500 households or more each and five officials, as medium with 300 plus households and four officials, or as small with around 100 households and two officials.

The feudal commune administrations were organizationally diverse, depending on their local peculiarities. Commune administrative units were characterized by their own cultural and social features, economic development level, natural conditions and population sizes. This is also the common trend in building the local administration model in many countries around the world.

Fourthly, supervisory activities constituted a compulsory requirement for self-rule local administration model.

During the feudal time, the State applied numerous measures to control the management and operation of grassroots administrations. The village chief election results had to be considered and censored by superior mandarins. If frauds were detected in the election and the elected village chiefs failed to meet the prescribed criteria, they would be delisted and downgraded to be commoners and the district mandarins would be penalized[4]. Besides, the State also organized regular tests, usually once every three years, to assess the management capability of village chiefs and do away with incapable commune headmen.

Apart from the above-mentioned moderate measures, the feudal states were also resorted to harsh measures to punish the whole villages or communes. For instance, King Le Du Tong (1706-92) ordered to raze Da Gia commune (Ninh Binh province) to the ground as villagers declined to lead a honest life, but only plundered or even killed people passing by their villages. In 1827, the Nguyen dynasty, after suppressing Phan Ba Vanh’s uprising, leveled the entire village of Tra Lu (Giao Thuy district, Nam Dinh province). Though these were rare cases, they revealed that the monarchy did not permit self-rule villages to exist outside the state laws and disciplines.

Pluses and minuses in building the self-rule local administrations during the feudal time

Through a long period of existence and development, the village self-rule regime revealed the following pluses and minuses:

Pluses:

The village self-rule constituted a factor to limit the king’s power and restrict the monarchy’s arbitrariness and autocracy. In the executive aspect, the feudal state permitted commoners to elect heads of local administrations. In the legislative aspect, the feudal state recognized village conventions (documented village customs and practices) as part of the state law. On the judicial plane, the commune level was considered the first to process disputes in villages, which should be reconciled and settled at the commune level before they were submitted to the district authority. Economically, the feudal state applied the regime of dividing land to people under specific regulations but still respected the village power on the principle: “Land of a village will be divided by that village”. So, the village self-rule regime restricted the king’s power in various aspects. All feudal dynasties found it necessary to promulgate policies suitable to village communities as if the states took to confront the villages, they could not well perform their functions and in the long run fall into crises and decadence.It helped reduce the state budget burden in wage payment to village officials, which were annually paid by the villages themselves. Besides, the royal court did neither worry about order and security in villages nor dispatch troops to maintain order and security in villages.Village conventions were recognized by the State as the effective tool for village management, “greatly contributing to the formation and promotion of dynamism, autonomy and consciousness of every village community in solving vital issues in life and forming the habit of respecting and observing the common principles of community”[5]. Being part of the state law, the village conventions supported the state law in regulating the social relations in villages, which the state law could not reach.The village self-rule regime helped form a democratic lifestyle in village community activities, as manifested in the participation in the exercise of state power. The State recognized and delegated a fairly extensive autonomy to villages without intervention in villages’ internal affairs. Villages only performed such duties as payment of taxes, public labor and conscription while being entitled to elect village chiefs and commune headmen and participate in the settlement of village affairs. Villages could establish their own self-rule institutions such as “giap” (sub-hamlet consisting of about 10 households each), “phe” (faction), “phuong” (guid), “hoi” (association), etc., where everyone could join regardless of social position, education and economic status. Village democracy was also seen in the organization and operation of the village administrative apparatus, with the termed election of every village position, the preservation of rich and distinctive cultural values of the village community, the conservation of the precious tradition of patriotism against foreign invasion, moral principles, benevolence and righteousness, learning fondness, etc.Minuses:

The village self-rule regime also revealed some limitations.

Village democracy during the feudal time was a form of incipient democracy. Communes only acknowledged the equality and democracy among commune members as their membership rights, but not recognized the personal rights and human rights of individuals in their capacity as independent entities. Commune democracy did not rely on human liberation and the respect of human rights, but only tightly bound humans in the commune relations and ensured the equality only when people were commune members. This led to the community’s intervention and supervision in the process of individual development and individuals had to obey standards formed by the community.The management apparatus was established with full power like a “petit royal court” with the village’s absolute power over village members, thus making villages a favorable environment for village officials and landlords to manipulate power and for the emergence of tyranny, thus making the state policies invalid and commoners’ livelihood more miserable.Village conventions remained to be an effective village management instrument until the 18th - 19th centuries, when numerous troublesome and complicated customs and practices as well as negative practices appeared, thus making them a tool for the village management apparatuses to manipulate powers as “petit royal courts”.The village self-rule regime contributed to forming a habit of giving more prominence to customs than to the state law. Villagers were accustomed to live with village conventions, customs and practices but not with the state law. It also gave rise to ideology of factionalism, departmentalism and localism, which lead to contradictions with the state interests and laws as well as the idea that “the king’s rule of behavior comes after the village customs”.Various dynasties were aware of the double-face nature of the traditional institution and applied measures to recognize with control this tradition in order to tap the positive aspects of village self-rule tradition while restraining its side effects.

Under the Early Le dynasty, with a strong central administration and a developed centralism, the State strictly controlled villages. Yet, during the Le-Trinh time, the State failed to strictly control villages, hence the self-rule regime was manipulated by tyrant landlords. Things were not better under the Nguyen dynasty, when the State applied political and military measures to subdue villages in vain, and finally the self-rule was abused by local tyrants and landlords to oppose the State in the name of villages and control the villages in the name of the State.

In short, taking into account the historical tradition, the current demand and development trend, Vietnam has grounds to study the organization of local administration according to the decentralization and autonomy model at the commune level in order to exploit the historical experience in handling the relations between traditional self-rule and state management and to promote the positive aspects of the self-rule tradition while restraining its negative effects. This has the practical significance for the building of self-rule local administration model in the new context. The study and application of self-rule local administration model in Vietnam must stem from the nature of the State and the structure of the Vietnamese territory in order to raise the dynamism, creativity, management effect and efficiency of the local administration and promote democracy while ensuring the uniform state powers.-

[1] Village conventions in northeastern Asian countries such as China, Japan and Korea only dealt with separate matters such as grave land, risk (fire, earthquake, etc.) prevention and fighting. Village conventions in Vietnam dwelt on more and diverse issues relating to almost all aspects of the village life. This demonstrates higher level of self-rule and autonomy in Vietnamese villages.[2] “Hoi Dong Ky Muc” was the Council of village elders who were aged 60 or over and heads of family lines or leading officials.[3] The Institute of Sino-Nom studies: A number of Vietnamese legal documents in the 15th- 18th centuries, the Social Science Publishing House, volume 1, p.234.[4] Ibid, “Thien nam du ha tap”, volume 1, the Social Science Publishing House, 2009. p.302.[5] Nguyen Thi Viet Huong (2001): Ancient village politico-legal ideology and its impacts on Vietnamese society”, LL.D thesis, the State and Law Institute, p.144.