Tran Thi Hoa

Hanoi Law University

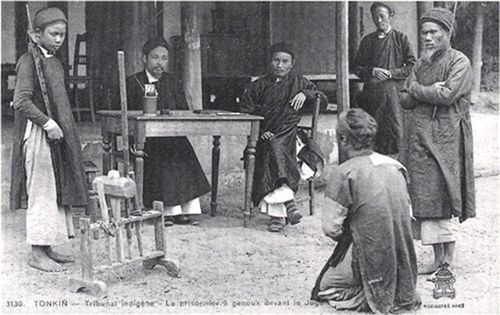

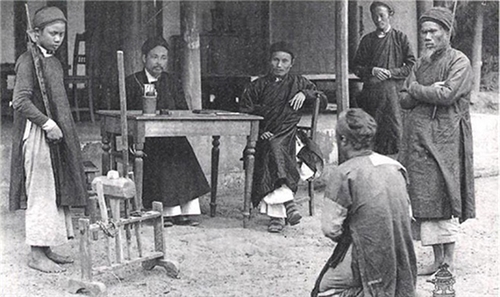

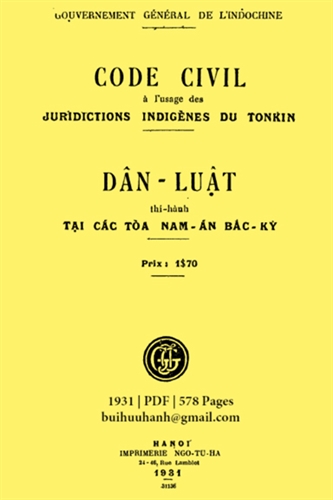

In the early 20th century, after decades of ruling, the French colonialists planned a political reform of Indochina, including Vietnam. In the legal area, they directed the compilation of many new codes in replacement of old feudal laws of the Nguyen dynasty. During this period they promulgated a dozen of new codes, including “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” (the Tonkin Civil Code), which was compiled from 1917 and enacted in the name of the Hue royal court in 1931.

In 1917 the Indochina Governor issued a decree setting up a Vietnamese-French committee for drafting a Code titled “Bo Dan Luat thi hanh tai cac toa an Bac Ky” (The Civil Code for application at Tonkin courts). This committee worked tirelessly for four years and completed the first volume with 91 articles on people and property in 1921. In 1927, a board of advisors on Vietnamese laws and regulations was established, composed of a number of French and Vietnamese experts for research into traditional customs and regulations on family, inheritance, cult-portion of heritage, helping the supplementation and finalization of the Code, which was officially promulgated in 1931.

While the Tonkin Civil Code inherited many provisions of Vietnam’s old codes; Hong Duc Code and Gia Long Code, its drafters used numerous law-drafting techniques and adopted the code structure, legal form and contents of the French Civil Code (1804) and the Swiss Civil Code (1912). It also reflected many Vietnamese customs and practices in its peculiar provisions different from those of Western and Chinese laws. Thus, the Code was widely seen as a typical Vietnamese code during the French ruling period.

|

| The cover page of the Tonkin Civil Code__Photo: https://vietbooks.info |

The Code’s structure

The Tonkin Civil Code had a preamble and many volumes, a structure greatly influenced by the French Civil Code. Each volume comprised many parts and was divided into chapters, sections and articles.

However, certain alterations were seen in the Tonkin Civil Code. Firstly, it was divided into four volumes instead of three as the French Civil Code. Secondly, the French Civil Code’s Volume III dwelt on modes of establishing ownership rights in 20 parts, including Part I on Inheritance and Part III on Contracts and Contractual Obligations. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese Code dealt with “Inheritance” in Part XI of Volume I right after the parts on marriage and family as inheritance in Vietnam was closely associated with family. Volume III of the Tonkin Civil Code provided contracts and contractual obligations. Notably, the French Civil Code did not provide ways of producing evidence related to civil procedures, whereas the Tonkin Civil Code had an additional volume, Volume IV, on evidence-producing methods, including ways of receiving, assessing and using evidence in civil cases.

So, although having a structure is similar to that of the French Civil Code, the Tonkin Civil Code saw some adjustments made to suit the scope of application in northern Vietnam then as well as the characteristics of local legal culture.

The Code’s contents

The Tonkin Civil Code adopted legal concepts and categories from European laws. Such concepts in civil law as nationality, civil status, document, birth certificate, legal person, ownership right, possession right, contract... were introduced into the Code. Especially, its final part “Lexique” defined the legal terms and concepts used in the Code, facilitating the proper understanding of its provisions. Throughout thousands of years, a major limitation of Vietnam’s feudal law is the lack of a system of general and specific legal concepts and specific provisions on jurisprudent concepts and categories. The adoption of a system of legal concepts and categories from the French Civil Code marked an important step of development in Vietnam’s civil law in general and the Tonkin Civil Code in particular, laying the foundation for building the civil law of independent Vietnam in modern time.

The Tonkin Civil Code also applied various principles of French civil law. Previously, Vietnam’s feudal law borrowed from Chinese feudal law such principles as principle of no punishment without law, principle of favoritism, principle of joint responsibility examination, principle of kin concealment… which, however, were not prescribed officially. Yet, under the French rule, many important principles were introduced in the Tonkin Civil Code’s preamble, including the principles of law promulgation, non-retroactivity, adjudication in case of non-availability of relevant legal provisions, non-rejection of cases, equality before law, respect for and protection of private ownership rights, etc. These principles were not only established in French law but also constituted an achievement of the western legal culture in its development process. The adoption of these principles significantly changed the Vietnamese law.

Regarding specific civil law institutions, the Tonkin Civil Code introduced the ownership institution of the French civil law, one of the most fundamental institution of civil law. It provided two forms of ownership: ownership by legal persons and private ownership. Influenced by the western jurisprudence, the Tonkin Civil Code also divided property into two groups: immovables and movables. Besides, it clearly established the owners’ basic rights to possess, use, benefit from and disposal of their property, etc.

In the Tonkin Civil Code, there were provisions on contracts similar to those of the French Civil Code. In Vietnam’s feudal law, matters related to contracts had never been treated as a separate institution but only regulated with few provisions mainly on trading, hiring and borrowing. In its third volume, the Tonkin Civil Code specified contractual matters in a systematic way, from the definition of contract to addressing contractual parties, including those considered incapable to enter into contracts such as minors and persons banned by law. Other contractual matters regulated by the Code include conditions on the contractual validity, contractual forms, invalid contracts, contractual obligations, etc. All these created a major reform on contracts in traditional Vietnamese law.

Regarding marriage and family, the Tonkin Civil Code contained many provisions on legal procedures in marriage. Vietnamese feudal law mainly regulated marital relations by customs and Confucian rites but had no provisions on marriage declaration for registration in civil status books as in the western countries. Article 91 of the Tonkin Civil Code stated: “After the marriage is declared before the civil status mandarin and entered the register, the husband-wife relationship has been established”.

Regarding divorce, the Tonkin Civil Code required divorces be carried out at court. According to Articles 116, 117 and 124[1], the husband and wife or either of them could apply for divorce at the court and only the court could permit their divorce when there was one of the reasons prescribed by law. In addition, many contents in this institution were influenced by the western law, such as the condition on marriage being the consent of both the man and woman, contract on marital property, unilateral or bilateral divorce.

The inheritance institution in Vietnamese feudal law was supplemented with a number of contents from the French Civil Code. Article 310 of the Tonkin Civil Code provided: “The inheritance opens immediately after the bequest leaver dies” while the feudal law provided that the heritance would open at the end of the mourning for parents (after three years). The Code also provided: “Inheritance is opened at the place where the dead person last resides” (Article 311, similar to Article 720 of the French Civil Code). Besides, it provided the heirs’ capacity in Article 313, similar to Article 725 of the French Civil Code; the priority order of heirs, and legal procedures for inheritance.

Reservation of traditional elements of feudal law

Despite adopting many contents of the French civil law, the Tonkin Civil Code still reserved a number of Vietnam’s traditional cultural elements. Firstly, it retained a peculiar long-lasting form of ownership, namely the village ownership. This form of ownership was closely associated with a constant in the Vietnamese political, economic, social and cultural life, which was the village’s self-rule during the French-ruled time. Secondly, the Code still recognized some types of traditional land and property under the feudal law, such as cult-worship property. The provisions related to this type of land were also reserved as seen in Article 430 of Code, which stated: “Property used as cult-portion shall not be transferred and subject to any limitation of time” or in Article 436, which stated: “Cult-property shall be handed down throughout the line of descent and after five generations become the common property of the family line”.

Thirdly, the Code’s marriage and family institution kept many feudal traditional cultural and legal elements according to traditional customs and practices. The Code still recognized and protected polygamy while maintaining the feudal patriarchy by setting the condition that young couples would not be allowed to marry without their parents’ consent (Article 77); if they were bound by blood ties (Article 75) or being in the mourning for their grand-parents or parents (Article 78), etc. It also kept provisions which allowed husbands to unilaterally apply for divorce for the reason that their wives committed adultery or abandoned their husbands’ families despite being called back (Article 118) or wives to apply for divorce for the reason that their husbands left the families for more than two years without plausible reasons and failed to take care of wives and children (Article 119).

Lastly, the Code retained numerous contents on inheritance, an institution related to many traditional cultural practices of the Vietnamese. It provided the traditional inheritance of cult-portion of heritage, specifying the inheritance percentage (Article 398) and the priority order of inheriting cult-portions. For inherence of common property, the Code kept various feudal legal provisions as well as Vietnamese traditional customs and practices, providing: “Property left without testaments shall be divided equally among children, sons as well as girls” or “for heirless couples, fathers, mothers, wives and husbands are all entitled to inheritance (Article 338). It did not recognize concubines’ right to inheritance (Article 364).-