Tran Hong Nhung LL.D

State Administrative Law Faculty

Hanoi Law University

Types of recruitment of mandarins in feudal Vietnam

In feudal Vietnam from the 15th to 19th centuries, mandarins were recruited mainly through “nhiem tu”; “khoa cu”; and “tien cu” or “bao cu”.

Nhiem tu was recruiting children and grandchildren of courtiers and court officials, based on their forefathers’ eminent services to the country. Khoa cu meant recruiting mandarins through various competitive examinations. “Tien cu” and “bao cu” both meant recruitment through senior court officials’ recommendation and guarantee.

These types of recruitment were applied differently from time to time.

During the Ly and Tran dynasties (1009-1400), nhiem tu was the major method of recruitment, by which various positions in the central and local administrations were assigned to royal family members. This method continued to be used in subsequent periods although it was no longer the major one.

|

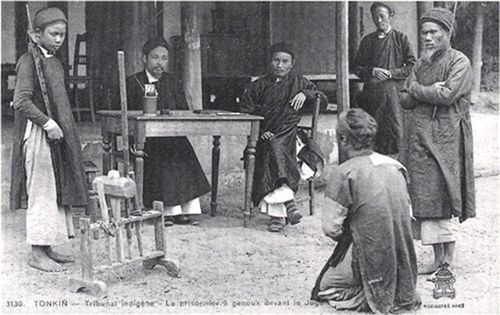

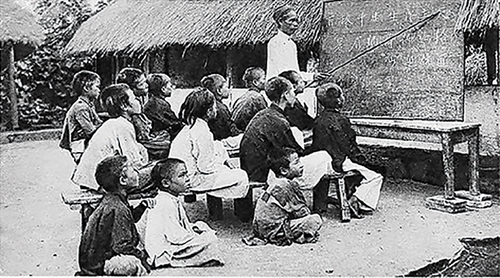

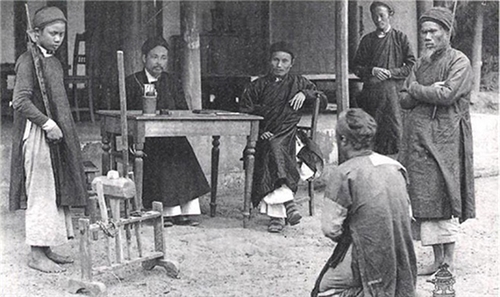

| A drawing illustrating the scene of an examination in the Nguyen dynasty__Photo: Le Perit Journal |

Khoa cu was first introduced in 1076 under the Ly dynasty. From the Tran kings on, it gradually became a common practice of mandarin recruitment (held once every seven years), then the dominant method of recruiting mandarins under the Late Le dynasty ((1427-1789) and Nguyen dynasty (1802-1945).

Tien cu and bao cu, also called “tuyen cu” (nomination-based recruitment) under the Ly and Tran dynasties, was applied more often during the Late Le and Nguyen dynasties.

As compared to nhiem tu and tien cu or bao cu, khoa cu was the best method of recruiting talents for many reasons.

Firstly, a unified set of recruitment criteria were applied nationwide, thus ensuring publicity and transparency and encouraging the self-training efforts of people who had a sense of purpose to become mandarins.

Secondly, examination candidates were equal in opportunity (except for those disqualified for their personal histories and morality) as they were entitled to participate in examinations, regardless of their social class, economic status or ages; if having passed the examinations, they all had the chance to be appointed as mandarins.

Thirdly, it created a link between study, examination and politics and promoted a society conducive to education, culture and individual talents. Mandarins who studied hard and passed examinations were all good at literature and history, knew how to care for people and possessed high social governance capabilities.

Fourthly, khoa cu provided a correct assessment of mandarins’ capabilities according to specific, uniform, objective and impartial criteria, preventing clique grouping.

Lastly, the recruitment through competitive examinations could select more mandarins than the two other methods, thus meeting the increasing requirements of national management of the feudal states.

From the Late Le dynasty to the Nguyen dynasty, khoa cu became the major method of recruiting mandarins, mainly through “Thuong Khoa” (general examination) with the doctorate examination and “Che Khoa” (restricted examination). The doctorate examinations included “Thi Huong” (inter-provincial examination), “Thi Hoi” (pre-court examination) and “Thi Dinh” (court examination), the most important examinations. From the first examination organized in 1075 under King Ly Nhan Tong’s rein to the last one organized in 1919 under King Khai Dinh’s rule, the Vietnamese feudal dynasties had organized 183 (or 184 according to some documents) examinations which found out 2,898 doctors, most of whom were appointed to important positions in the state apparatus.

In order to build up a large contingent of public servants, the feudal dynasties sought to organize competitive examinations in a scientific and strict manner, which were improved from time to time. Throughout these four centuries, khoa cu was highly valued in the Le and Nguyen dynasties. During the Le dynasty, particularly the Hong Duc era (1460-1497), competitive examinations most strongly developed as compared to other dynasties (Historian Phan Huy Chu in “Lich trieu hien chuong” (Chronicles of Past Dynasties’ Charters). During the Late Le dynasty, the competitive examinations were no longer strict, with poorer results. In the Tay Son period (1778-1802), King Quang Trung paid more attention to Nom (Chinese transcribed Vietnamese) education but without a firm foundation to substitute Sinology for its thousands of years’ influence in Vietnam. Within its short tenure, the Tay Son did not organize any significant competitive examinations. Under the Nguyen dynasty, khoa cu was modeled after the Le dynasty’s but much more advanced.

Measures to improve mandarin recruitment

Holding preliminary selection to ensure the quality of examination candidates

From the Late Le dynasty, prior to Thi Huong, examination candidates were required to submit their life stories of three generations. The Regulation, called “Le Bao ket” was promulgated in 1462 under King Le Thanh Tong. According to the Regulation, only persons with clean life stories and good virtues could be registered in the books of candidates. The Regulation provided: “District and commune mandarins had to guarantee that only virtuous persons can declare in candidates’ books. Those who were undutiful, incestuous, untruthful and crafty are not allowed to sit for the examinations even though they are literate. Candidates’ identity cards must clearly state their communes, districts, ages, titles of their fathers and grand-fathers.” Besides, those who were going into mourning for their fathers or mothers, or for their paternal grand-parents whose cults they had to observe, were also not allowed to sit the examinations.

If meeting the rules provided in Le Bao ket, candidates could sit for a written test “Am ta co van” (ancient text dictation) and only those who passed this test could participate in Thi Huong.

District and commune mandarins were tasked to conduct the preliminary screenings. They had to certify the candidates’ educational and literary levels and were responsible before law for their certification. If candidates were unable to do examination exercises, leaving their examination papers blank, the testing mandarins would face dismissal or demotion.

Organizing various examinations under a strict process and order

During the Le thru Nguyen dynasties, only candidates who passed the round of tests can participate in three subsequent examinations, one after another. Thi Huong were organized at local levels. Only those who passed Thi Huong and got the bachelor diplomas and complete a training course at Quoc Tu Giam (royal college) could sit for Thi Hoi, a national pre-court examination, before taking the final Thi Dinh, which was organized only once a year at the royal court and for which the King personally set the examination questions and marked the examination papers. Those who passed Thi Dinh were called doctors of different ranks. They would then be appointed to positions suitable to their capabilities and qualification. For people who passed Thi Huong and Thi Hoi, they would be posted into the system of mandarins of local administrations, while those who topped such examinations would be promoted to the rank of mandarins of the central court.

According to historical records, the Thi Hoi in 1502 drew in 5,000 candidates, but only 61 passed while in 1514 only 43 out of 5,700 candidates passed the examinations[1]. Therefore, most of the Thi Hoi graduates were talents who made great contributions to the national construction and defense such as Nguyen Trai, Chu Van An, Truong Han Sieu, Luong The Vinh, whose names have come down into Vietnam’s history.

Regarding the examination contents, King Le Thanh Tong set the regulations on Thi Huong in 1462 and Thi Hoi in 1472, under which candidates were tested in four subjects: The Confucian Five Classical Books; royal decree drafting; poem writing; history and literature[2]. Meanwhile, Thi Dinh candidates had to write an essay on the theme set by the King himself, who also marked the examination papers and ranked the graduates. They were considered proficient in history and literature, required to thoroughly understand the national situation, to acquire the ruling skills and apply their knowledge to the solution of social issues confronted the nation.

The recruitment of office clerks was also strictly organized through examinations once every three years, with candidates required to possess good hand-writing, grasp the rule of drafting documents and taking notes, and know to do calculations.

Strictly selecting examiners and accurately and impartially mark examination papers

Under the Nguyen dynasty, examiners were classified into inside and outside categories. Inside examiners included 4 to 16 “quan so khao” (preliminary marking mandarins), 4 to 6 “quan phuc khao” (re-marking mandarins), and 2 “giam khao” (examiners). Outside examiners included “quan chanh chu khao” (the head examiner), a deputy-head examiner and two assistants.

Preliminary marking mandarins were chosen from among bachelor holders while re-marking mandarins were selected from fifth or sixth rank-literary mandarins.

Examination papers were first marked by re-marking mandarins with the comment “Uu” (distinction), “Binh” (good), “Thu” (average), or “Liet” (failure), then marked again by re-marking mandarins before transferring to examiners, who were selected from among literary mandarins of fourth or fifth rank, to conduct the final marking inside the examination sites and re-checked the examination papers before they were handed over to the head examiner who was fully authorized to approve the examination papers.

If making any errors, examination paper-marking mandarins would be subject to bonus deduction, demotion or relief from position.

In order to prevent wrong-doings by marking mandarins, the feudal examination rules clearly stated that mandarins who had any relatives sitting for examinations or were mobilized to work at the same examination sites with relatives must apply to abscond from work.

Preventing cheating in examinations

For this purpose, the feudal dynasties applied the following major measures:

The first one was to issue specific regulations on each stage of an examination. For instance, to attend Thi Huong, candidates had to prepare their tents and personal belongings and were not allowed to bring along books and materials into the examination sites. They were neither allowed to wear double-layer clothes, but only single-layer ones. Entering the examination sites, they would have their personal belongings carefully checked, and were required to stay in their own tents, without moving around or going to other candidates’ tents. They had to know the names of the kings, lords and mandarins and accurately cite words of saints and sages in the books and were forbidden from profaning the taboo names, talking noisily or falsely declaring their names and ages. Violators would be severely penalized.

All examination papers would have their detachable heads cut off before being sent to the royal capital for review. After each examination, those who were assign to examine and supervise the examination would be required to send reports to the royal capital.

The second measure was intensifying the supervision of candidates as well as examiners during the examination.

From the Le thru Nguyen dynasties, “Bo Lai” (the Ministry in charge of organizational and personnel affairs) and Quoc Tu Giam (the royal college) were assigned the main responsibility for training and recruiting talents through competitive examinations. In order to guarantee impartiality and combat negative practices in the examinations, these offices were answerable to the king and submit to the oversight of “Bo Le” (the Ministry in charge of education, culture and health) and a mandarin called “Lai Khoa” (person in charge of supervising Bo Lai), which was tasked to inspect examination and recruitment activities. If detecting any signs of cheating and negative practices, Lai Khoa was entitled to question Bo La” and report them and propose handling measures to the king.

In the course of examinations, the supervision within the examination site was undertaken by two mandarins. “Ngu su” (royal advisors) would oversee the observance of examination-site regulations by mandarins and report to the king, while “de tuyen” (martial mandarin), assisted by soldiers, would supervise candidates and invigilators. Outside the examination sites, “quan de doc” (commander of a provincial army) would organize day-and-night watch.

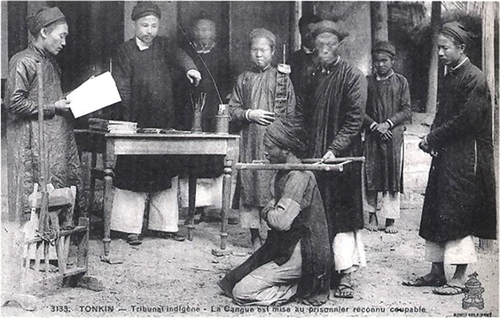

Strictly handling acts of cheating was the third measure. “Quoc trieu hinh luat” (The national criminal code) of the Le dynasty clearly defined and severely punished acts of cheating in competitive examinations. For example, it stated: “Those who enter the examination site without permission to sit for examination for other people shall be sentenced to exile and life-long ban from taking competitive examinations and from work assignment” (Articles 2, 3 and 5).

Upholding the viewpoint that “talented and righteous persons are the national treasure” (King Le Thanh Tong’s words), the feudal dynasties in Vietnam attached special importance to the system of competitive examinations. Particularly, the feudal states from the 15th thru 19th centuries enforced many policies on competitive examinations in order to recruit talents in service of the nation and people.-