Pham Thi Thu Hien L.L.D.

Hanoi Law University

In the system of Vietnamese feudal laws, the Confucian and legalist viewpoints always influenced the regulation of forms of handling violations committed by mandarins on official duty. Confucian values were institutionalized into the laws as Confucianism gave prominence to mandarins’ obligation to constantly train themselves for self-improvement. To the king they had to be absolutely loyal and totally devoted. To the people they must be incorrupt and exemplary and fulfill three duties “phu, giao and hoa” (serving the people, enriching people and educating people about politeness and uprightness). Mandarins had to well perform their duties. Otherwise, they would be duly punished. It can be said that mandarins’ obligation to train themselves was a prerequisite for determination of mandarins’ responsibilities in Vietnamese feudal law.

The legalist viewpoint laid emphasis on three elements: “Phap” (law), “the” (power and authority) and “thuat” (skills). For laws to be enforced and powers and authorities to be exercised, the rulers had to apply ruling skills, one of which was to generously reward those who record merits and to severely punish those who commit wrongdoings. This is also the basis for understanding regulations on handling of breaches committed by mandarins in performing their official duties.

The penalty of “biem tu” (rank demotion)

According to Professor Vu Van Mau, “biem” was a punitive form of demotion applicable to incumbent mandarins or degrading of mandarins’ virtues*. In the course of duty performance, mandarins who recorded merits or achievements would be promoted in ranks while those who committed administrative violations would be subject to demotion. Article 27 of the Le dynasty’s “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” (the Royal Court’s Penal Code) prescribed five levels of demotion by: one rank, two ranks, three ranks, four ranks and five ranks.

In addition to demotion, the offending mandarins also had their salaries and allotted land areas reduced, and were subject to an additional penalty of “danh roi” (whipping) or “danh truong” (heavy-stick stroke). Article 46 of “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” said: “Those who are demoted by one rank would be subject to 50 “roi” (whippings). Those who are demoted by two ranks would be subject to 60 “truong” (heavy-stick strokes), by three ranks to 70 “truong”. Those who were subject to “do” (hard labor) would be given 80 “truong”; those who were “luu” (exiled) to a near district would be punished with 90 “truong” or to a far district with 100 “truong”.

Feudal legislators specified acts of violation in a number of duties to be subject to this punitive form such as protection of “thai mieu” (royal ancestors’ temple); maintenance of security and order in a royal palace; conduct of royal ceremonies; protection of royal mausoleums and tombs; and judicial work.

Meanwhile, feudal laws also permitted violators to pay money in replacement of rank demotion, with larger sums for higher ranks. Article 22 of “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” stated: “The sum of 100 “quan” (an ancient currency unit of 100 coins) for first-rank mandarins, 75 “quan” for second-rank mandarins, 50 “quan” for third-rank mandarins, 30 “quan” for fourth-rank mandarins, and 25 “quan” for fifth-rank mandarins.”

“Biem” was regarded as a penalty aiming not only to reduce the incomes of offending mandarins but also to influence their careers, honors and prestige. Through this measure, the feudal state recovered parts of loaves and fishes bestowed to mandarins with a view to raising their sense of responsibility for official-duty performance.

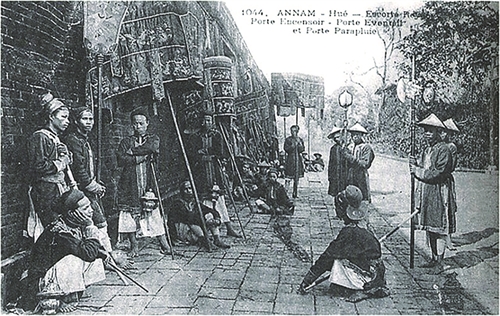

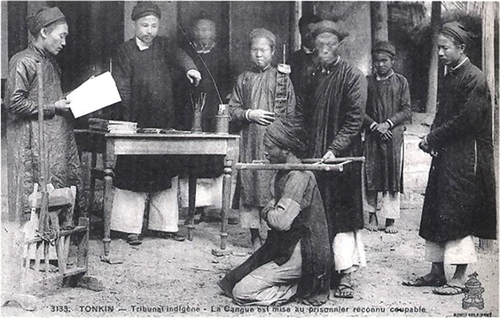

|

| A court hearing in feudal time__Photo: Internet |

The penalties of “Ngu hinh”

Both “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” and “Hoang Viet Luat Le” (The Royal Laws and Regulations of Vietnam under the Nguyen Dynasty) prescribed “Ngu hinh” (five criminal penalties), including “Xuy hinh” (whipping). “Truong hinh” (heavy-stick stroke), “Do hinh” (hard labor), “Luu hinh” (exile) and “Tu hinh” (death sentence).

The first four penalties were applied to violations committed by mandarins in a number of administrative duties: “Xuy hinh” applied to violations in paper work management; “Truong hinh” to violations in the management of security and order in the royal palace, conduct of royal ceremonies, protection of royal mausoleums and tombs, drafting of royal decrees,etc.; “Do hinh” to offenses in border-gate protection or soldier recruitment; and “Luu hinh” to violations in protection of royal security and order, and soldier recruitment.

Feudal legislators based themselves on the severity of violations to decide which penalty of “Ngu hinh” applicable to mandarins who breach the official-duty regime. Article 60 of “Hoang Viet Luat Le” stated: “Upon receiving a royal decree for implementation, those who deliberately commit violations would be subject to 70 “truong”. Those who delay the implementation for one day will be given 50 whippings, one more day, the penalty will increase by one level, but only to the maximum of 100 whippings.”

Any of “Ngu hinh” could be either imposed independently or in addition to other penalties. According to Article 1 of “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat”, “Xuy hinh” can be accompanied by pecuniary fine or rank demotion or applied separately; “Truong hinh” can be applied together with exile, hard labor or rank demotion.

“Ngu hinh” were considered a deterrent to offenders.

Pecuniary fine

Pecuniary fine was mentioned for the first time in Vietnam under the Ly dynasty. According to “Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu” (The Complete History of Great Viet), in 1326 Truong Han Sieu was fined with 300 “quan” for slandering justice mandarins Pham Ngo and Le Duy. Fine was provided more clearly in the laws of the Le and Nguyen dynasties, applied to all illegal acts, including official-duty violations.

Different fine levels and bases were provided in “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” and “Hoang Viet Luat Le”.

“Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” provided in Article 26: “Offenses shall be fined at three levels: the first level of between 300 and 500 “quan”, the second level of between 60 and 200 “quan”, and the third level of between 5 and 50 “quan”.

These fine levels applied to different offenses committed in various fields. For instance, the level of 5-50 “quan” applied to offenses in office security; night patrol in a royal palace; protection of state-owned mountains and forests; breaches of royal ceremonies, etc. Meanwhile, the level of 60-100 “quan” would be applied to acts of harassment of people or violations in the management of prisoners. The level of 300-500 “quan” would be imposed on breaches of royal ceremonies.

Besides, Article 233 of “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” provided a fine of under five “quan” applicable to mandarins who failed to show up at meetings after being summoned.

Feudal legislators also set different fine levels with smaller amounts of money for unintentional violations or low-ranking mandarins and larger sums for intentional violations or high-ranking mandarins.

Meanwhile, “Hoang Viet Luat Le” applied pecuniary fine to official duty-related offenses based on mandarins’ salaries. According to its Article 7: “Mandarins, military or civilian, low- or high-ranking, who are subject to 10 whippings, shall be fined with one-month salary; subject to 20 or 30 whippings, one more month’s salary will be added to the fine; 40 or 50 whippings, three more months salaries will be added to the fins; subject to 60 heavy-stick strokes, one year’s salary will be subtracted, etc.”

Based on such fine levels, “Hoang Viet Luat Le” specified acts and scopes of violation: one month’s salary for violations in recruitment of mandarins and conduct of royal rituals; two months’ salary for violations in recruitment of mandarins; one salary grade lowered for loss of royal documents or seals; three salary grade reduction for violations in financial or state secret management, etc.

The fine levels varied between two Codes, “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” set the minimum fine of under one month’s salary and the maximum of eight months’ salary. Meanwhile, under “Hoang Viet Luat Le”, the minimum fine was one month’s salary and the maximum was one year’s salary.

As compared to “biem” or “Ngu hinh”, pecuniary fine was an independent penalty not to be applied together with other penalties. However, it was applied together with remedial measures in certain cases.

Other punitive forms

In addition to the three major penalties above, “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” and “Hoang Viet Luat Le” introduced a number of other punitive forms such as “phat bong” (cut or subtraction of loaves and fishes); “cach chuc” (removal from office); confiscation of property; and compensation of material evidence.

“Phat bong” was a measure of cutting or subtracting loaves and fishes for a given time. “Cach chuc” was a measure forcing the offenders to leave their positions, either undertaking other jobs for given periods (“cach luu”) or being sent to work in other places (“cach nhiem”). These were additional penalties, which were always applied in company with others.

Confiscation of property and compensation of material evidence were the measures of remediation of consequences caused by violations.-