Truong Vinh Khang

State and Law Institute

Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences

Le Thanh Tong ascended the throne in 1460 when he was 18 years old and died when he was 56. He was considered the most talented ruler in feudal Vietnam as assessed by “Dai Viet Su Ky toan thu” (the Complete Book of the Historical Record of Great Viet): “The King founded a strong state, expanded the territory and brought prosperity to the nation; he was truly a talented, heroic ruler who could be compared to Yu Ti of the Han dynasty and Taizong of the Tang dynasty.”

|

Statue of King Le Thanh Tong in Van Mieu (Temple of Literature), Hanoi__Photo: Internet |

During his 38-year tenure he created a strong centralized monarchy through specific policies and measures, with a focus on developing a contingent of mandarins with clearly defined role, responsibilities and criteria.

Like other kings who took Confucianism as the ideological foundation for pacifying and ruling the country, Le Thanh Tong understood that “mandarins constitute the roots of peace or revolt” and “the good or bad rule in a country depends on the good or bad king and mandarins.”[1]. Yet, what is important is not his statement on the role of mandarins but his untiring efforts to organize and manage a contingent of truly allegiant and professional mandarins.

His specific policies on building the contingent of mandarins were derived from his idea on the role and responsibility of mandarins. He once said: “Virtuous and talented people are the vitality of the nation. If the vitality is strong, the country’s position is solid. If the vitality is weak, the country’s position is weak and feeble. Therefore, all clear-sighted kings care for the fostering of talents, selection of scholars and development of the vitality. Scholars are so important to the nation that great respect must be paid to them”[2] In December 1463, when speaking to mandarins of Bo Lai (the organization and personnel office), the king recalled that idea, saying: “Tu Ma Quang (Sima Guang) once said gentlemen constitute the root of peace and prosperity while petty men constitute the source of trouble and disaster. You and I have sworn before heaven and earth to employ gentlemen and abandon petty men and must day and night bear this in mind.”[3]

In the king’s view, mandarins had to meet two criteria: “Hien” (virtue) and “Tai” (talent), synonymizing the qualifications of a Confucian gentleman. These two criteria were translated by Le Thanh Tong into specific requirements on mandarins.

According to the king, the virtue of mandarins must be displayed in three respects: Allegiance to the king (responsibility before the king); love and care for the interests of the people (responsibility before people); and possession of civil-service ethics (responsibility in civil service).

Mandarins were first and foremost subjects of the king, assisting the king in ruling the country. Hence, mandarins have the duty to show reverence and faith to the king and strictly his orders. Le Thanh Tong said: “The good or bad rule in a country depends on the good or bad king and mandarins. In the family, children must show dutifulness to their parents and in the country the subjects must be allegiant to the king.”[4] His idea was expressed by Nguyen Don Phuc in his doctoral thesis written in the year of Mau Tuat (1478): “In peaceful time, you must respect the king and help people; when the country is in danger, you must sacrifice your life for the country; only by doing so you fulfill the subject’s duties and do not feel ashamed with your academic reputation.”[5]

Besides his statements on the ruler-subject relationship, Le Thanh Tong introduced specific measures to guarantee this relationship. In the Hong Duc Code, he devoted many articles to punishing violations of the duty of allegiance to the king: Mandarins who decline to attend the Minh The rite (the rite to swear allegiance to the king) will be sentenced to corvee labor or exile (Article 170); mandarins in the royal court or localities who attempt to rebel will be beheaded (Article 103); mandarins who show disrespect to the king will be degraded, exile or death (Article 125); mandarins who disobey the king’s orders will be sentenced to demotion or exile if the orders are not important or to exile or death if the orders are urgent (Article 222), etc.

However, following other wise kings, Le Thanh Tong permitted mandarins to speak out their ideas and advice to the king on the enforcement of his ruling policies. He even earnestly encouraged mandarins to do so, saying “If I make any mistakes, you should frankly point them out but not cover them up.”[6]

King Le Thanh Tong perceived that mandarins should assist the king in ruling the country and bringing prosperity and happiness to the people. Therefore, he considered the people’s trust was an important moral standard of mandarins. He demanded mandarins to care for the material and spiritual lives of commoners and show responsibility to them in two aspects: to be polite and upright so as to win the people’s credit; and to develop farming work for people to have enough food and clothing.

The king placed special stress on mandarins’ civil service ethics. To him, mandarins must be diligent and devoted to their work and clean and incorrupt. He said in a decree: “In the past, many Bo Hinh (the office in charge of legal affairs and adjudication), Thua Ty (the office in charge of administrative, financial and judicial issues) and Hien Ty (the office in charge of local affairs), provincial and district mandarins conducted adjudications in an arbitrary manner, left many cases unsettled, and took bribes. None of them worked for the people; therefore, injustice had been done on many people. From now on, mandarins must be just and fair in assessing those should be retained and who should be dismissed in order to choose good people to perform fair adjudication work.”[7]

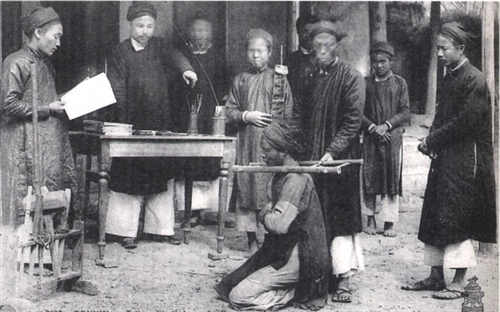

|

Stele of Doctors in Van Mieu (Temple of Literature), Hanoi__Photo: Internet |

Corruption, bribery and collusion were viewed by Le Thanh Tong as evils, which should be actively prevented. An evidence is that in many questions raised at “thi dinh” (court competition-examinations), the king often asked about the situation and causes of corruption, bribery and collusion and their counter-measures.

The king attached importance to fighting these evils by means of law. He was the first to absorb the rule on avoidance, which prohibited local officials from serving in their places of origin in order to prevent corruption and favoritism, introduced it in the Hong Duc Code and strictly applied it to “thi huong” (inter-provincial competition-examinations) and “thi hoi” (pre-court competition-examinations).

The king also introduced regulations on rotation of mandarins and closely supervised their implementation.

Thinking that “only when mandarins are well paid, can they be motivated to do good things,” King Le Thanh Tong issued specific regulations on salaries, rewards and fines for mandarins, which became a state regime from the Early Le dynasty.

Besides the Hong Duc Code, the king also issued different regulations to punish those who commit corruption, bribery or collusion.

In the first lunar month of the year of At Mui (1475), he issued a regulation to ban bribe taking in construction and repair activities.

In the second month of the year of Mau Tuat (1478), he made a decree ordering local mandarins to report on mandarins who were honest and righteous or corrupt and diligent or lazy to the king for promotion or demotion.

In the third month of the year of Tan Suu (1481), he issued an order urging military commanders in districts and provinces to justly adjudicate “those who squeeze soldiers or people for self-seeking purposes without thinking of state law.”

In the sixth lunar month of the same year, he issued an order demanding local administrations to examine and degrade or demote mandarins who had since 1461 committed bribery and to dismiss commanders who failed to collect taxes fully or who ordered soldiers to give money and work for their personal affairs in order to “get rid of corrupt mandarins.”

In the eighth month of the year of Quy Mao (1483), the king announced amnesty for prisoners, except those who had committed corruption, bribery or serious crimes.

In the fifth lunar month of the year of Giap Thin (1484), he issued a decree requesting local administrations to report within three months mandarins who committed corruption or bribery to “Ngu Su Dai” (the office in charge of personnel affairs) for adjudication.

In the fourth month of the year of Dinh Mui (1487), the king issued a regulation that corrupt mandarins would be dismissed and conscripted to the army in Quang Nam province.

Talent, in Le Thanh Tong’s perception, was the other compulsory criterion of mandarins. He decreed: “The king’s rule requires talented people. This is considered the root of prosperity for a nation.”[8]

Mandarins’ talents were demonstrated in their capability to assist the king in ruling the country. This capability must be displayed in two aspects: educational level and practical capability. The educational level is expressed mainly the ability to thoroughly know literature and history as well as Confucianism. It must be evidenced through academic diplomas. The practical capability is demonstrated through administration work. Although not being explicitly and systematically stated, the king’s idea on this issue was expressed in his decrees, orders, decisions as well as specific measures on examinations and assessments.

According to a royal decree on the mandarin system, persons recruited to work as mandarins, whether for the royal court or localities, must be graduates of “thi huong”, “thi hoi” or “thi dinh”. “Those who graduate as one of the three laureates of “thi hoi” will be appointed to be chief mandarins of provinces or districts or royal court envoys. Other graduates will be appointed to the post of district chief or mandarin.”[9] Even commune chiefs, who were not royal court officials, had to be selected on the basis of their educational level: “Only those who are literate and have talents will be recruited to handle cases and affairs for people.”[10] Historian Phan Huy Chu wrote: “By that time, royal offices and localities employed laureates of various competition-examinations. Even local offices recruited graduates of such competition-examinations. So, their officials were all scholars.”[11]

Le Thanh Tong regarded academic diplomas as the basis for appointment. Yet, according to him, academic diplomas must truly reflect the educational level. During his tenure, he step by step regularized competition-examinations and applied different measures to encourage learning and increase educational quality. As a result, from the Le Thanh Tong’s time on, “thi huong” was organized annually for all people (except criminals and entertainers). Graduates from “thi huong” could attend “thi hoi”, which was organized once every three years at the royal court. “Thi hoi” graduates were entitled to participate in “thi dinh” where the king personally made examination questions and presided over the examiners’ board. Prior to Le Thanh Tong, only seven competition-examinations were organized to select 89 doctors, while under his rule, 12 “thi hoi” were organized to select 501 doctors.[12]

Le Thanh Tong also valued the practical capability of mandarins. In addition to the two common forms of recruitment of mandarins, namely “tien cu” (nomination) and “tap am” (selection from relatives of courtiers with meritorious services), and competition-examinations, Le Thanh Tong introduced a new form called “bao cu” (recommendation for appointment) in his decree issued in the year of Giap Thin (1484). “Bao cu” allowed royal and local offices to recommend talented, knowledgeable, honest and upright persons to Bo Lai for consideration and appointment. It also clearly defined the responsibility of recommenders, saying that they must state the nominees’ talents, knowledge and integrity and that if such persons later commit a despicable or corruption crime and fail to fulfill their tasks, they will be punished.

Moreover, Le Thanh Tong established a mandarin assessment regime in order to measure mandarins’ practical capability, honesty, integrity and diligence as the basis for their commendation, punishment, transfer, promotion, demotion or dismissal.[13] In 1470, he issued an order to organize examination-based assessments of mandarins. In 1478, he ordered the dismissal of mandarins who failed to fulfill their tasks and the selection of talented people for replacement. In 1488 he gave an order to hold preliminary examinations once every three years and final examinations once every nine years before deciding on promotion or demotion. In 1489, he issued a decree on relief of office of mandarins who were old and incapable to perform their work.

So, in the history of Vietnamese monarchies, Le Thanh Tong left precious experiences on the use of mandarins on the basis of talent and virtue. He focused on building a contingent of allegiant and professional mandarins, considering this a premise for effective state administration. This is also the goal as well as motive force of the socialist administration of the people, by the people and for the people throughout the current process of administrative reform in today Vietnam: building a contingent of civil servants is always considered the most important breakthrough.

Le Thanh Tong attached great importance to the two criteria of virtue and talent of mandarins. These are also the requirements set by President Ho Chi Minh on revolutionary cadres, who must be “hong” (virtuous) and “chuyen” (professionally qualified). The guidelines and policies of the Vietnamese Party and State on building the contingent of cadres and civil servants also have adopted two similar criteria. In the current administrative reform, we are striving to build a contingent of clean and capable civil servants, attaching importance to both capability and morality.

In order to have virtuous and talented mandarins, Le Thanh Tong applied various measures such as education to enhance self-imposed discipline and the sense of responsibility; clear definition of rights and responsibilities of mandarins in combination with severe punishment of their violations; standardization of the processes of training, recruitment, employment, examination, inspection and supervision of mandarins; fight against corruption, bribery and collusion; establishment of the regimes of rewards and penalties, and reasonable salaries. Among these measures, Le Thanh Tong concentrated on the regularization and clear definition of responsibilities of mandarins, standardization of the processes of training, recruitment, examination and test of mandarins, and anti-corruption fight. In other words, along with applying general measures, he identified priority measures. For instance, to fight corruption, he viewed bribery and imperiousness as the burning problems and saw high-ranking mandarins in the royal court as the key targets, then applied specific measures to thoroughly deal with these problems. This is truly a valuable legacy left for us by Le Thanh Tong.-