Assoc. Professor, Dr. Nguyen Thi Viet Huong

Lang (village) is a Viet ethnic group’s word referring to a traditional unit of settlement of Viet peasants in rural areas, with its own territory, infrastructure facilities, organizational structure, customs and practices, psychology, perceptions, characters and even dialect or accent which are relatively stable over the course of history.

First villages appeared very early in the Hung King era (about 3,000 years ago) as a result of social division and transformation of clan communes.

Xa (commune) is a Sino-Vietnamese term given to a grassroots administrative unit in Viet-inhabited rural areas, which has to pay taxes and provide military service to the central state.

Communes came into existence as a result of the state’s intervention into traditional units of settlement of rural Viet people in 621 when Vietnam was under the rule of China’s Tang dynasty. Through the ups and downs of history, communes had undergone numerous changes in scale and managerial organization but always held the role as grassroots administrative units of the state, and were built and strengthened by the state on the basis of conserving villages.

In traditional Vietnamese society, at least in the northern delta and midland regions, there are two types of communes. The first is composed of single-village communes. Such a commune had Hoi dong ky muc, a traditional governing body consisting of village elders, and an official service apparatus representing the state in the village. In administrative documents, the name of the village was also the name of the commune. The second type consists of communes each having two or more villages. In these communes villages are called thon - a Sino-Vietnamese word. Until the early 20th century, single-village communes were common in the northern delta. So, though being two different words, in most cases village and commune denote the same entity. In the minds of many generations of Viet people villages were communes and vice versa.

As a unit of settlement, a traditional village retained some noticeable characteristics of oriental rural communes, which emerged very early in Vietnam, even before the formation of the Van Lang-Au Lac state.

First, every village was a community living stably on a territory with specified boundaries written in its code and cadastral register. In each village lived many clans, each consisting of many families which were independent production units living close to one another as neighbors. Kinship and neighborhood were two ways of co-inhabitation in traditional Vietnamese villages.

Second, each village was a self-sufficient entity. In the northern delta, most traditional villages engaged in multi-functional economic activities including agriculture, handicrafts and trade, in which agriculture was the main livelihood. There were also craft villages where inhabitants lived on one or more than one craft and trade villages where inhabitants earned a living by trading at rural markets or forming itinerant trade guilds. These villages, however, were not many and never became handcraft or trade centers totally separated from agricultural work. Generally, any traditional village had a subsistent economic base, an underdeveloped commodity economy and production processes based on manual tools and methods and family experiences.

Third, every village had public rice fields and a mixture of common ownership and private ownership. In primitive times, rural communes were established on land areas under common ownership of these communes. Peasants tilled on public rice fields and enjoyed yields and only had to contribute part of their yields to public funds of their communes. When the state was established, rice fields in each village came under the supreme ownership of the state, represented by the king, but villages still had the right to possess these land areas and periodically distributed them to villagers for cultivation to enjoy yields and pay taxes to the state.

|

| Duong Lam village gate, Son Tay town, Hanoi__Photo: Minh Duc/VNA |

The power of villages over land areas under their management was incrementally diminished due to the state’s intervention. Public land areas in the villages also decreased as a result of the long process of privatization, starting from the Ly dynasty. By the mid-18th century, private rice fields accounted for a remarkable percentage of the whole cultivation areas. However, for various reasons, rice fields under private ownership in traditional villages were very scattered and small. It is this smallholding private ownership that led to another characteristic of traditional villages, that is in each village neither a large stratum of landlords possessing most of rice fields to exploit the rest of villagers nor a class of people who had sufficient economic power to control or gain socio-political advantages in the community was formed. On the contrary, villagers were divided into many rich and poor groups depending on their possessions and farming methods.

Public rice fields of villages were narrowed but did no disappear because they were always added from various sources: rice fields donated by mandarins and landlords and families. Therefore, until before the 1945 August Revolution, most villages still had two types of public rice fields: those owned by the state and managed by villages and those under common ownership of villages formed from various sources (donated by individuals or belonging to same-age associations…).

Fourthly, traditional villages were isolated and granted relatively political independence. As grassroots administrative units, villages had only three main obligations toward the State, namely paying taxes, contributing hard labor and providing military service. Internal affairs were resolved by villages themselves without the state’s intervention. In each village there was a mechanism for handling village affairs through the village’s code and social institutions. A village can be regarded as a combination of institutions which gathered members on the basis of blood ties (families and family lines), neighborhood (lanes and alleys), age group, socio-political status, occupation or voluntariness. While each institution admitted and managed its members by organizational principles, charter and perceptions of duties, morality and public opinion, villages managed these institutions by customs, decisions and codes. Depending on its nature, each institution played a certain role in carrying out activities in the village, ensuring village life. These social institutions and codes constitute a self-management and autonomous mechanism of villages, enabling them to exist in isolation from other villages and independently from the state.

Fifthly, each village had common customs, beliefs, psychology, characters and language.

All villages had their own marriage customs (e.g. the groom’s parents had to pay a sum of money to the bride’s village), funeral customs, ranking order, promotion celebration banquets as well as communal houses, pagodas and temples, the most important of which were communal houses where villagers got together and the village’s tutelary god resided.

As a place of closed society where peasants lived their whole lives for generations, each village became a setting to sustain and develop its community psychology. This psychology was expressed in the sense of village community (territory boundary and material and spiritual values…), which formed the bonds of attachment to the village (the spirit of unity, sharing of joy and sorrow, active performance of assigned duties, a way of life always thinking about one’s native land …). This community psychology of each village was generally shared by individual villagers.

A village was also a community of shared ethos which were easily distinguishable from those of other villages in terms of walk, voice, gesture, attitude and behavior, both good and bad but typical of the village. Each village, though sharing a river with or separated by just a path or a fence from another, had its own accent, which was kept unchanged over thousands of years, respected and protected by villagers as a distinctive trait of their village.

From residential units, villages became grassroots administrative units of the central state and were step by step feudalized.

About the process of turning villages into grassroots administrative divisions, historical records reveal that grassroots administrative divisions (xa) emerged in rural Viet in the 7th century when the country was under China’s Tang rulers. The Chinese rulers established such divisions on the basis of villages of Viet people (one commune per village), with households regarded as units for population management.

From the early 10th century, the Khuc clan and successive Vietnamese dynasties maintained communes as grassroots administrative divisions and appointed mandarins to run their administrative affairs.

Particularly, under the reign of King Le Thanh Tong (1442-1497), a raft of drastic and thorough reform measures were introduced to manage villages, making them truly a grassroots network of state power.

In 1828, King Minh Mang (Nguyen dynasty) ordered massive administrative reforms including rules that permitted each village to have one village mayor and one to three deputy chiefs depending on the number of male villagers and clearly defined criteria, duties and powers of village mayors.

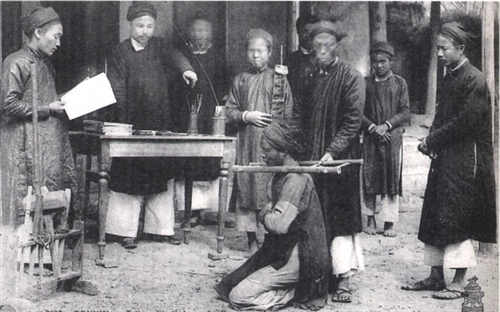

After completely conquering Vietnam, French colonialists continued regarding villages as grassroots administrative divisions and maintained the traditional managerial apparatus to rule the countryside for the purpose of colonial exploitation. In 1921, when the national liberation movements broke out in Vietnam, the French colonists were compelled to intervene deeply in the organization of traditional villages by carrying out a village administration reform focusing on replacing Hoi dong ky muc with a council of family line representatives; rectifying activities of village officials by redefining the functions, powers and duties of the village mayor and deputy mayors, issuing new village codes... These policies were adjusted in 1927. In 1941 Hoi dong ky muc were re-established, marking the failure of these policies.

Concerning the process of feudalizing villages in terms of customs and thinking, until the 10th century, social relations in traditional villages were governed by customary rules. Since the Ly dynasty (1009-1225), the central state sought to supervise and control village rules while step by step promulgating laws to regulate social relations in villages.

|

| A corner of Dong Ky communal house, Dong Ky ward, Tu Son town, Bac Ninh province __Photo: Internet |

Ideologically, since the 10th century when the feudal class became mature and wanted to build a centralized monarchic state, confucianism step by step infiltrated into the superstructure of Vietnam’s feudal society. The royal court and confucian scholars made every effort to disseminate confucianism into villages. In reality village communities assimilated confucianism in both voluntary and involuntary ways, which profoundly changed the social and spiritual lives and thinking of villages. First, traditional conceptions, ways of living and customs became deeply imbued with confucianism. Second, confucian scholars grew in number and held important positions not only in the state apparatus but also in village communities. And third, the polarization of classes in villages increased toward a confucian hierarchy. Generally speaking, since King Le Thanh Tong’s reign, social relations in villages tended to be both confucianized and legislated.

The process of incorporating the ranking system of the feudal state into villages began in the mid-Tran era, when the state appointed commune-level mandarins, and was promoted under the reign of King Le Thanh Tong. By the mid-15th century, when confucian philosophy and feudal relations had dominated many aspects of village life, the issue of social status became a central concern of social life in every residential unit. In most villages, small or big, long established or newly formed, agricultural or craft or trade… every villager (male and official resident) would be assigned a place in the order of precedence based on his state-bestowed rank, academic degree, property, age or sometimes descent. This order of precedence was very complicated but basically consisted of two groups: people of upper class (superiors) and people of lower class (commoners).

In a nutshell, Viet villages had developed from units of settlement of peasants through the long history of the nation into complete and flexible socio-economic entities, communities with their own territories, assets, beliefs and customary rules, and residential units with shared sentiments and destiny, which existed relatively independently in the context the state imposed on them an administrative apparatus, a legal system and confucianism. In other words, Vietnam’s traditional villages were unified entities which existed concurrently in isolation due to the closed traits of ancient rural communes reinforced by the process of transformation into small-peasant villages and under the influence of the process of turning them into grassroots administrative divisions. This is the fundamental state determining the entire physiognomy of Vietnamese village life throughout the course of history.-