Prof. Dr. Tran Ngoc Duong

Former Chairman of the National Assembly Office

In the regime of democracy and socialist rule of law, the state power is delegated by the people, which must, therefore, be inevitably controlled. The state power is often documented by constitutional provisions to define the mandates and rights of the legislative power, executive power and judicial power. The recognition and development of the principles of power delegation, coordination and control between legislative and executive bodies through various constitutions are linked with the historical contexts of the nation in each particular period.

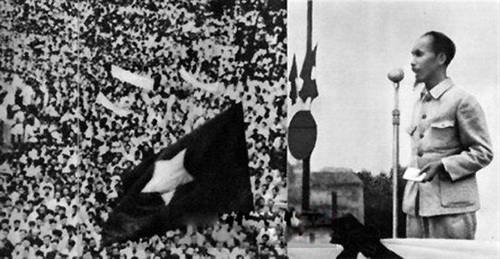

The 1946 Constitution

Under the 1946 Constitution, “Nghi Vien Nhan Dan” (People’s Parliament) was the supreme state power body of the People’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam; the Government was the highest administrative body of the nation; the judicial bodies included the supreme court, appellate courts, and second-level and primary courts; and judges were appointed by the Government. The 1946 Constitution’s makers realized the importance of the executive power, which was closely associated with the two others - executive and judicial powers. The first Minister of Justice of the People’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Mr. Vu Dinh Hoe, wrote: “All powers must be, in principle, concentrated in the hands of the supreme representative body - Nghi Vien Nhan Dan, but the key apparatus for the exercise of powers is the Government with all administrative and professional agencies.” The State President’s term was five years, longer than the Parliament’s term of three years. The Prime Minister led and administered the Cabinet, which was accountable to the Parliament for its political line.

The 1946 Constitution embraced two fundamental issues. First, the Constitution guaranteed the independence of legislative, executive and judiciary powers. Second, it affirmed in principle that the Parliament, Government and people’s courts were all the highest bodies vested with the state power, each holding a branch of state power. These provisions showed the clear-cut division of powers among the highest state power bodies, while guaranteeing that the people’s power is supreme and the state power arises from the people’s power.

The coordination between the legislative and executive branches in performing the State’s functions could be clearly seen in that the legislative body was empowered to set up and supervise the operation of the executive body, while the executive body was empowered to submit bills for the legislative body to approve by vote.

Regarding power control, the legislative body controlled the executive body by participating in the establishment of the executive body through the election of the President; ratified the President’s selection of the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s selection of ministers; voted on bills and budgets submitted by the Government; and ratified treaties which were signed with foreign countries by the Government. The Parliament was entitled to control, criticize the Government and question members of the Government; to decide on the establishment of a special tribunal to adjudicate the President, Vice President or a cabinet member who committed the crime of treason; to disband the Government by casting the vote of confidence on the Prime Minister and the Government. Vice versa, the executive body would control the legislative body as clearly seen in that the State President was empowered to promulgate decrees with similar validity as laws; to request the Parliament to review laws it passed; to raise the question of no-confidence on the Government for re-discussion at the Parliament within 24 hours. The President was not accountable to the Parliament for any liability except for the crime of treason; the Government was entitled to arrest parliamentarians in case of flagrant delicto, but had to notify the arrest to the Parliament’s Standing Committee within 24 hours.

|

| Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc chairs the cabinet September regular meeting on October 2__Photo: Thong Nhat/VNA |

Remarks

First, the relationship between the legislative and executive bodies under the 1946 Constitution was established on the basis of the necessity to have a strong government to deal with a multi-party Parliament as well as complicated issues of the country at the time. President Ho Chi Minh said: “This Government will attach importance to realities and endeavor to work, taking advantage of the country’s independence and territorial integrity to build a new state of Vietnam.”

Second, the above relationship was built on the basis of creative application of basic principles of the power separation theory to Vietnam’s practical circumstances in order to create a power-controlling mechanism between the legislative and executive branches as well as a dual executive regime in which both the President and Prime Minister held and shared the executive power. Power separation was in essence nothing but division and coordination toward control, using power to control power for the purpose of preventing the abuse of power.

Third, the 1946 Constitution not only clearly defined the functions, tasks and powers of various state agencies but also sought to control power between legislative and executive bodies. However, the control was rather moderate. Specifically, the Parliament could cast votes of confidence on the Government as a collective or on individual cabinet members but the latter was not allowed to do the same against the Parliament, which could be dissolved only when it was so declared by itself. Such provision ensured the unity of state power which belonged to the people. In this respect, the President might request reconsideration. If the Parliament still insisted with the similar number of votes against the Government as previously, the Government would be naturally disbanded. The President could cast a veto which, however, would become null and void if at least half of total parliamentarians adopted such resolution. So, in all circumstances, the final decision rested with the Parliament though the President was entitled to curb its decisions.

Fourth, with the adoption of the power separation mechanism, the 1946 Constitution reflected the characters of legislative and executive bodies. The People’s Parliament was empowered to decide matters related to the national destiny and to pass laws affecting the common interests of the entire society. This institution demonstrated a new form of democracy of the republic established for the first time in a feudal semi-colonial country as Vietnam. The nature and mode of organization and operation of the People’s Parliament then fit the practical situation of the country in the wake of the 1946 General Election, with the participation of various political forces in a people’s democracy structure.

Under the 1946 Constitution, the Government was strong, and accountable to and independent from the Parliament and capable of controlling the Parliament. The President headed the State and personally directed the operations of the Government. The head-of-state function merged with the executive function and the President actually held the executive power. Like some other countries, each Government decree must bear a minister’s signature besides the President’s and it was that minister to be accountable to the Parliament for legal consequences of that document[1]. The Government was actually the highest administrative body of the nation. The Government had to resign if it lost a confidence vote in the Parliament. This political responsibility constituted a foundation for a strong, stuffed and decisive Government.

The 1959 Constitution

Under the 1959 Constitution, the National Assembly’s powers were institutionalized more specifically and further enhanced as compared to the powers of the People’s Parliament defined in the 1946 Constitution. The constitutional and legislative powers all belonged to the National Assembly and the scope of legislative power was also broadened. The National Assembly was empowered to oversee the enforcement of the Constitution, to make laws, to decide war and peace and general amnesty, etc. In case of war or other special circumstances, the National Assembly itself might decide to extend its term and apply necessary measures to ensure its and its deputies’ activities.

The head of state was separated from the executive branch. The President was not empowered to veto but only to formally promulgate laws. His powers were greatly narrowed, only representing the State and no longer administering the operation of the Government. Most of the President’s activities were restricted to the executive function symbolizing the sustainability and unity of the nation. The most important role of the then head of state was to coordinate three branches of power while under the 1946 Constitution the President not only held a branch of power and coordinated the branches of power but also controlled their operation.

The Government Council was established as the executive body of the supreme state-power body and the highest state administrative body of the People’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam (Article 71). With its capacity as the executive body of the National Assembly, the administrative function of the Government Council was weaker than that prescribed in the 1946 Constitution. Thus, its organization and functions were greatly changed and its powers narrowed. In its relationship with the legislative body, the Government Council became a weaker institution.

The 1959 Constitution did not provide the control of the legislative body by the executive one. The position and role of the National Assembly as the supreme state-power body were elevated. No body or title in the state apparatus was empowered to control activities of the National Assembly. The 1959 Constitution prescribed the control of the executive agency by the legislative one with these provisions: The Government Council takes responsibility and reports its work to the National Assembly and National Assembly Standing Committee; and National Assembly deputies are entitled to question the Government Council, which the National Assembly cannot overthrow through the confidence vote mechanism. Instead, the institution of removal from office of individual members of the Government was put into place as the legislators in this period viewed that “the dissolution of the Government would lead to a political crisis and a disruption of power, failing to ensure the unity of power.”[2]

Remarks

First, the legislative-executive relationship in the 1959 Constitution was built on the principle of socialist power centralization. Only the National Assembly - the supreme representative body of the people - was vested with full state power and became the supreme state power body. Other high-level state agencies were only the administrative and judicial bodies of the supreme state power agency, which were all established, dismissed and delegated powers directly or indirectly by the National Assembly, and had to report their work to the National Assembly.

Second, due to the unclear power delegation, the Government Council’s independence was restricted. The National Assembly status was heightened and vested with a lot of powers. The Government Council was only the highest administrative body of the National Assembly, hence being dependent on the latter.

Third, as the state apparatus was organized after the model of power centralization, the Constitution gave prominence to the role of the National Assembly, hence the control between legislative and executive bodies was much dimmer than that prescribed in the 1946 Constitution, which was mainly the control by the National Assembly over the Government but not vice versa. National Assembly deputies could be arrested and prosecuted only with the consent of the National Assembly or the National Assembly Standing Committee when the National Assembly was in recess.

Fourth, the 1959 Constitution failed to spell out the required nature of the legislative and executive bodies. While the National Assembly did not demonstrate itself as a controlled institution in the promulgation of laws as it possessed full constitutional and legislative powers; once laws were passed by the National Assembly, the State President could not demand their reconsideration. Regarded as the executive body of the National Assembly, the Government Council’s administrative function was insignificant. It was assigned fewer tasks and powers than the Government in the 1946 Constitution. The confidence vote mechanism was no longer applied.

|

| Prime Minister Trinh Dinh Dung answers NA deputies’ questions about issues under the jurisdiction of the Government__Photo: Van Diep/VNA |

The 1980 Constitution

Under the 1980 Constitution, the National Assembly was defined as the supreme state-power body and the sole body vested with constitutional and legislative powers. It elected the Council of Ministers, decided on issues of national importance and performed the supreme oversight of the entire operation of the State. Moreover, the National Assembly could also set for itself other tasks and powers when necessary. It can be said that the 1980 Constitution was culminated in the principle of socialist power centralization, concentrating the state power into the hands of the National Assembly. This led to the unclear relationship between legislative and executive powers.

The relationship between the Council of Ministers and the National Assembly was one-way. The Council of Ministers was not empowered to control the National Assembly, but only the latter had the power to control the former as the principle of power centralization negated the equal power and mutual control between the legislative and executive bodies.

The 1980 Constitution stated that the legislative body controlled the executive body in various forms: The Council of Ministers was responsible for and reported its activities to the National Assembly and the State Council. National Assembly deputies could question members of the Council of Ministers and request them to explain or supply documents on necessary matters. The National Assembly was empowered to dismiss the chairman, vice-chairmen and other members of the Council of Ministers. In its relationship with the National Assembly, the Council of Ministers was only entitled to issue sub-law documents, guiding the implementation of documents promulgated by the National Assembly or the State Council. It could not control and become the counterpoise of the National Assembly. All decisions of the Council of Ministers were collectively discussed and made by majority; the individual roles of the Council chairman and ministers were minimal, which reflected the ideology of collective mastery which was deeply rooted in the organization and operation of the state apparatus. The Council of Ministers was tied to the National Assembly and its administrative role was fairly small.

Remarks

First, as strongly influenced by the socialist ideology, the 1980 Constitution was culminated in the concentration of state power into the hands of the National Assembly regarding the organization of the state apparatus. In its relationship with central state bodies, the National Assembly was given the almost absolute superiority, being the only body vested with the power to supervise other bodies, but not vice versa. The idea of power delegation, coordination and control between legislative and executive bodies was dimmest as compared to the two previous Constitutions. The less independence of different functions led to the less effective operation of the state apparatus. It can be said that with this Constitution, the idea of power separation and its reasonable points were almost totally negated.

Second, the legislative-executive relationship in the 1980 Constitution was hardly defined and there existed overlapping in the performance of functions, tasks and powers of bodies. The National Assembly acted as a Pooh-Bah, doing many jobs at a time and intervening in the managerial activities of the Council of Ministers. The executive agency was regarded a section operating under the direction of the legislative body.

Third, the 1980 Constitution failed to prescribe natures of different state institutions. With such a fully empowered National Assembly, no entity had the right to ask the National Assembly to review its decisions. The Council of Ministers had no full power even in the field of state management. Hence, it was unable to become a strong and decisive executive body. Moreover, in the spirit of collective mastery, the role of the chairman of the Council of Ministers was completely dim, with his specific powers being ignored by the 1980 Constitution. Therefore, this title was not considered an independent power institution as head of the Government defined in the 1946 Constitution. The 1980 Constitution did not prescribe the no-confidence vote mechanism applicable to the Government, thus failing to bring into play the sense of responsibility of members of the Council of Ministers and to create conditions for the National Assembly to be more active in the handling of members of the Council of Ministers.

The 1992 Constitution (revised in 2001)

Article 2 of the 1992 Constitution (revised) provided that the state power is unified and delegated and coordinated between state agencies in the exercise of legislative, executive and judicial powers. With this provision, three types of state power were mentioned for the first time in the constitutional ideology of power separation, thus recognizing the existence of three legislative, executive and judicial powers in the State.

The 1992 Constitution provided more clearly the division of power and responsibility between the National Assembly as the legislative body and the Government as the executive body. Concretely, the legislative power belonged to the National Assembly, the supreme representative body of the people and also the supreme state power body. The Government was defined as the executive body of the National Assembly, the highest administrative body considered a part of the National Assembly. Such provision was of important significance, aiming to affirm its relative independence, functioning to perform the state management which required prompt decisions as well as centralization and uniformity in the process of management.

On the coordination between legislative and executive bodies, the 1992 Constitution stated that the Government must abide by the Constitution, laws and resolutions of the National Assembly, ordinances and resolutions of the National Assembly Standing Committee. The Government was not empowered to veto draft laws of the National Assembly and to demand reconsideration of decisions of the National Assembly. However, being still influenced by the principle of power centralization, the 1992 Constitution provided a very limited control of state power, especially the National Assembly’s activities.

Remarks

First, the mechanism of division of tasks, powers and responsibility of state bodies in the 1992 Constitution was prescribed rather clearly. The National Assembly performed the functions of the legislative body; the executive powers, to a certain extent, belonged to the Government. However, the legislative, executive and judicial powers were not delegated to the three different bodies in an independent and equal manner; only the National Assembly held the legislative power while the executive and judicial powers were all exercised with the coordination between state bodies. The exercise of power was delegated not in an absolute manner. The Constitution did not prescribe clearly which bodies exercise the executive power and which bodies exercise the judiciary power, thus causing confusion to state bodies in the exercise of their respective powers.

Second, with the adoption of reasonable points of power separation to establish the legislative-executive relationship under the mechanism of power delegation and coordination, the 1992 Constitution contained some provisions to express the Government’s independence and accountability. In addition to the affirmation that the Government was the highest administrative body of the nation, not of the National Assembly, the Constitution clearly defined the jurisdiction between the Government and the Prime Minister, its leader. The clear definition of the Prime Minister’s powers in the Constitution gave him an independent legal position and real power in the state power structure. Rather than only determining the collective responsibilities of the Government as before, the 1992 Constitution spelled out the personal responsibilities of all the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Ministers, ministers and other members.

The 2013 Constitution

Basically, the 1992 Constitution’s provisions on the mechanism for exercise of the Government’s power were inherited and further developed by the 2013 Constitution to meet the requirements of building a law-ruled state. The guiding ideology in amending and perfecting this mechanism in the 2013 Constitution is to further clarify and give prominence to the law-ruled democracy in the organization and operation of the Government towards transparency, law compliance, control, consistency and smoothness in the exercise of powers. Apart from adjusting, further clarifying the tasks, powers and responsibility of each Government institution, the Prime Minister, ministers, heads of ministerial-level agencies, the new Constitution also made some changes in the exercise of powers, suitable to the nature and role of each of these institutions, increasing the transparency, flexibility and promptness, giving prominence to personal responsibility while ensuring the close association between these institutions in the exercise of executive and administrative powers.

Regarding the delegation of power between the legislative and executive bodies, the 2013 Constitution continues providing that the National Assembly is the supreme representative body of the people and also the supreme state-power body. However, in Article 69, it spells out two new fundamental points as compared to Article 83 of the 1992 Constitution, namely the distinction between the constitutional and legislative powers and the removal of the provision that the National Assembly is the sole body vested with the constitutional and legislative powers. The distinction between the constitutional and legislative powers constitutes one of the key requirements of democracy and rule of law. In a law-ruled state, the constitutional power must belong to the people who use it to establish the state power, including the legislative power[3]. Therefore, the constitutional power must be placed above the legislative power and the Constitution must be the document of highest legal effect, serving as a tool in the hands of people to delegate and control the state power.

The Constitution provides that the Government is the highest state administrative body exercising the executive power and serves as the executive body of the National Assembly. Moreover, the 2013 Constitution officially provides for the first time in Vietnam’s constitutional history that the Government exercises the executive power, which covers the following major operations: planning and administering national policies; making and submitting to the National Assembly draft laws; promulgating specific plans and policies as well as sub-law documents for realization of policies and laws already approved by the National Assembly; directing, guiding and administering the supervision of implementation of plans and policies; establishing the law-based administrative order; detecting, verifying and handling violations according to its competence or referring them to People’s Courts for adjudication according to the judicial procedures. This new provision demonstrates the clear-cut delegation of power between power branches. The Government holds the real power, being more independent, active and responsible in national administration and management. This not only demonstrates a new advancement in distinguishing the executive and administrative concepts but also affirms that the executive power constitutes one of three relatively independent branches of power in conformity with the viewpoints and principles of organization of the state power with the three state agencies in the exercise of legislative, executive and judicial powers.

Regarding the coordination between the legislative and executive bodies, unlike the Constitutions of 1980 and 1992, which provided the Government’s task “to guarantee the enforcement of the Constitution and laws,” the 2013 Constitution prescribes such task as “to organize the enforcement of law”, which constitutes an independent and special power of the executive system comprising the Government, the Prime Minister, ministers and local administrations at all levels. This demonstrates the relationship of delegation and coordination between legislative activities and enforcement activities of the two legislative and executive institutions.

Remarks

First, with the promulgation of the 2013 Constitution, the concepts of legislative power, executive power and judicial power, which are associated with the terms of legislative body, executive body and judicial body in the state apparatus, have been officially used. This is a new development of the 2013 Constitution as compared to the 1992 Constitution (revised), which failed to affirm which agencies were executive bodies and which were judicial bodies. Moreover, the new Constitution also clearly defines the collective responsibility of the Government as well as the personal responsibilities of the Prime Minister and Government members in their managerial activities.

Second, the 2013 Constitution adds some new contents on organizing the state power in Vietnam. That is, the state power is unified, being not only delegated and coordinated but also controlled in the exercise of legislative, executive and judicial powers. This is the principle governing the relationship between agencies when performing the legislative, executive and judicial functions as well as the correlation of their powers. This is a great development in the thinking of constitution makers as the revised 1992 Constitution did not mention the mutual control among power branches.

Third, the 2013 Constitution contains many new and progressive provisions to promote the prudent nature of the National Assembly, respect the rule of law and promoting the independence, proactiveness, creativeness and accountability of the Government - the body exercising the executive power. The National Assembly is no longer a body with total power as under the power centralization mechanism but a body holding a type of power in the power structure. The 2013 Constitution places the administrative nature of the Government above its executive character and officially provides that the Government exercises the executive power as delegated by the people, but not by the National Assembly as seen the previous socialist power centralization mechanism.

The collective working regime helps the Government be more democratic in making its decisions. However, the Prime Minister’s role as the leader of the Government is expressed through separate tasks and powers. The mechanism of accountability of Government members also witnesses changes: The Prime Minister is responsible to the National Assembly for the assigned tasks; reports on activities of the Government and the Prime Minister to the National Assembly. This provision inherits Article 54 of the 1946 Constitution, which said that the Prime Minister was accountable for the political line of the Cabinet. The new Constitution also provides that the Prime Minister, after being elected by the National Assembly, must swear to be loyal to the Fatherland, the People and the Constitution; Deputy Prime Ministers are responsible to the Prime Minister for their assigned tasks; the ministers and heads of ministerial-level agencies must take personal responsibility to the Prime Minister, the Government and the National Assembly for the sectors and fields under their respective charge. Like the Prime Minister, the ministers must also report to the people on important matters under their managerial responsibility. These new provisions aim to bring into play the personal capability, decisiveness and accountability of the Government members.-