King Le Thanh Tong (1442-1497)[1] recorded great merits in protecting the country’s territorial integrity, expanding the national frontiers and protecting the national sovereignty over land, sea and island borders. The Hong Duc Code in the king’s era appeared to be the most complete and progressive code of the Vietnamese feudal states, containing numerous articles on the defense of national territory.

Truong Vinh Khang

State and Law Institute

Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences

Building a unified state based on the territorial integrity

Though being defeated by Vietnamese in the Lam Son uprising (1418-1427) led by Le Loi, who regained independence for Vietnam and proclaimed emperor Le Thai To in 1427, China’s Ming dynasty never renounced its schemes to conquer Vietnam. In face of their repeated provocative actions, King Le Thanh Tong demanded his mandarins to resolutely preserve the land left behind by ancestors, without losing any part of mountain and river. Historical records wrote: “His excellency told the courtiers: We must preserve our land carefully, not letting anyone seize any part of mountain or any part of river left behind by king Le Thai To.”[2]

Even when the country was in peace, King Le Thai Tong kept heightening the awareness of the protection of national territory. In 1471, he told Le Canh Huy, the third highest-ranking mandarin of the royal court: “How could we abandon a meter of our mountain or an inch of our river. We must be firm in our debate, not letting them encroach step by step. If they reject, we can even send envoys to their royal court to clearly justify our right. Anyone who dares to present a meter of mountain or an inch of land left by Le Thai To to the enemy would be heavily punished.”[3] Such statement explicitly demonstrated Le Thanh Tong’s strong will to protect the national independence and territory, showing a fundamental political viewpoint in his perception of the state management responsibility.

It can be said that when ascending the throne, Le Thanh Tong had a great advantage that the country was enjoying peace. He inherited the country’s thousands-year ideological tradition of regarding the national land as sacred, the national sovereignty and territorial integrity as inviolable, and the national border as the critical fence of the country. So, in his perception of a centralized autocracy, the emperor’s power was associated with the strong development of an independent and sovereign nation. His idea of building an independent and unified state based on the territory preservation and expansion was consistently and clearly demonstrated in his specific policies.

First, in order to create the basis for affirming the national independence, Le Thanh Tong paid attention to the clear delineation of national boundaries. In his era, he twice ordered the drawing of national maps. The first time fell at the end of 1469, when he ordered: “To re-draw the maps of ‘phu, chau, huyen, xa, trang, sach’ (provinces, districts, communes, villages).”[4] The second time was in 1490: “In summer, the 5th of the fourth moon, to re-draw national maps with 13 ‘xu thua tuyen’ (provinces), comprising 52 ‘phu’ (towns), 178 ‘huyen’ (delta districts), 50 ‘chau’ (mountain districts), and 6,851 ‘xa’ (communes).”[5] As a result, the Hong Duc national land maps were drawn and publicized to people nationwide as an official state document on Dai Viet’s territory. Nowadays, these maps no longer retained their originality because of multiple duplications, but they have been recorded in official historical books and are famous in the history of the Vietnamese nation. What is more important is that the Hong Duc maps present a vivid evidence of Le Thanh Tong’s sense of preserving the national independence and unity.

|

| Stone dragons on Kinh Thien Palace’s staircase built during the reign of King Le Thanh Tong__Photo: Internet |

Building a strong national defense

King Le Thanh Tong’s policy on building a strong national defense was demonstrated in three aspects: building a crack and mighty army; attaching importance to the border protection; and eliminating the danger of ruling by feuds in the country.

Le Thanh Tong held that the country “should be always be guarded against dark schemes in order to firmly maintain security forever.” As a result, his prime concern was to build a strong army as the firm mainstay for the state. The king’s most important policy was comprehensive reform of the national conscription to build up an elite small army with a strong regular force and a massive reserve force ready for mobilization when necessary. This policy was initiated with the building of an army under the unified command of the royal court led by the king. “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” (the Criminal Law of the Royal Court), more commonly known as Hong Duc Code, contained 43 articles with strict regulations on the army. For example, Article 1 said: “Army officers who command thirty-thousand men or fewer or 50 soldiers or more but neglect training so that army ranks are not in good order, troops are not elite, or ignore army affairs, thus leaving military gears in bad conditions and in need of repair, or misappropriate public property, do their personal business while neglecting their military duties shall be punished by degrading or demotion, deportation and hard labor or exile, depending on the severity of their violations. If they decline to fight the enemies while committing the above violations, they shall be beheaded irrespective of the severity of their violations.”[6]

In the reform of the state apparatus, Le Thanh Tong abolished the title “te tuong” (the king’s first minister), strengthened “Bo Binh” (the Ministry of National Defense), established “Khoa Binh” (the Department of National Defense - an office not attached to the army but placed under the king’s personal direction) to oversee “Bo Binh” and the army, and re-arranged the system of military mandarins. Moreover, the conscription regime was re-organized toward building a regular army with two forces: the royal court’s army and the provincial army. Right in the first years of his rule, King Le Thanh Tong ordered the compilation of household registration books and the classification of men as the basis for implementation of socio-economic policies as well as military conscription. In 1470, the royal court issued a conscription rule that for a family with three male children, one of them would be conscripted into the regular army, one into the reserve force while the third would be exempt from military service. The State prohibited and severely punished the false declaration of the number of men, dodging of military service and desertion from the army. On the other hand, it expanded the scope of conscription exemption to outstanding students and provided incentives for army men. Article 387 of Hong Duc Code stated: “Males aged 16 and females aged 20 or older, who leave their land to their relatives or other persons for tilling shall face 80 ‘truong’ (cane beatings) and land confiscation. If it is due to war (conscription) or their wandering life, this law shall not apply.” Army men were given public land and had their land ownership rights protected. In addition, the “Ngu binh u nong” regime applied under the Ly and Tran dynasties, under which army men took turn to leave the army for agricultural production, was still implemented in the Early Le dynasty, even applied to the royal palace guards. This helped ensure production activities and reduce the military budget, ensuring balance between economy and defense. Thanks to these measures, the army in Le Thanh Tong time became a mighty force to protect the kingdom and the national independence. In reality, this army played an important role in preventing and stopping land encroachment attempts of the northern feudalists. Some of these attempts were noted in ancient historical records. For example, Pu Lan, a mandarin of the Ming dynasty in Guangxi province, dispatched troops to attack Ha Lang district of Dai Viet. They were defeated by the army of the Le dynasty and had to withdraw. Ming troops in Pingiang many times crossed the border for looting in Lang Son region, but were all driven away by Dai Viet army.

Regarding border defense, Le Thanh Tong implemented many appropriate border policies, such as organizing border forces to patrol and protect land and sea border areas and islands, recruiting tribal chiefs as court mandarins to rule ethnic minority areas and respecting customs and practices of ethnic minority people. Historical documents revealed that many people of the Deo family line in Muong Le, Cam family line in Tay An, Xa and Cam family lines in Hung Hoa, Vi family line in Lang Son[7], and Hoang and Be family lines in Cao Binh (Thai Nguyen), which were border localities, became mandarins of the Le dynasty. Under Le Thanh Tong’s reign, the heads of delta districts were all appointed by the royal court. But most mountain districts were assigned to tribal chiefs for management. To manage more closely mountainous regions in general and border areas in particular, the royal court also dispatched a number of high-ranking mandarins or their relatives to rule these regions and areas as well as defend the national frontiers.

Le Thanh Tong’s concern about the national borders and territorial integrity was demonstrated clearly through his attitudes and actions toward Chiem Thanh kingdom in the south. In his time, Dai Viet was involved in many disputes over border markers with Chiem Thanh and had to resort to military measures to defend the national border but without success. When Chiem Thanh launched a large-scale military campaign with “more than 100,000 marine and cavalry troops to attack by surprise Hoa Chau,” Le Thanh Tong personally commanded a counter-attack to defeat the Chiem Thanh army and marched directly to their capital city of Cha Ban (Do Ban citadel, An Nhon district of present-day Binh Dinh province), making Chiem Thanh the 13th province of Dai Viet.

The northwestern border region of Nghe An province to Quang Binh province, along Truong Son (Long Mountain) range, was originally ruled by tribal chiefs of the Cam family line. Under king Le Nhan Tong’s reign, Dai Viet occupied this region and renamed it from Bon Man to Quy Hop while still allowing members of the Cam family line to administer this region.[8] In the 10th reign year of Hong Duc, tribal chief Cam Nong rebelled and attempted to separate his region from Dai Viet. King Le Thanh Tong dispatched general Le Niem to suppress the rebellion, turning this region into a district, called Tran Ninh district, of Nghe An province.

For border guards who let enemies infiltrate into the country, they would be penalized according to their violations. Those who caught enemies would be rewarded: “Those border guards who fail to perform careful checks, letting enemies send information across the border or infiltrate into the areas under their management to spy on the local situation shall be sentenced to corvee labor, exile or death. Those who arrest enemies shall be awarded titles of nobility.”[9]

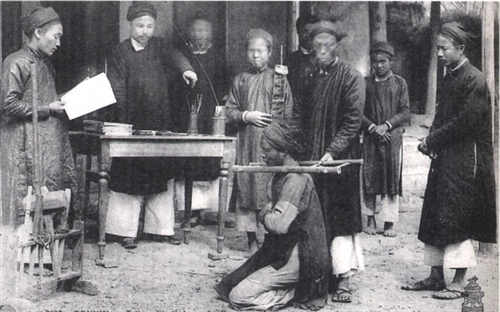

In order to prevent ruling as feuds and build an independent unified state, the royal court clearly defined the roles and responsibilities of district mandarins in localities: “To carry out patrols in localities, to advise and assist people… To investigate rebellious attempts and notify them to provincial mandarins for arrest of rebels while making written reports for use as evidence. Those mandarins who make truthful reports shall be promoted and rewarded; those who fail to report or make untruthful reports shall be severely punished. In case a robbery occurs in relation to a district mandarin, to file a separate petition at the yamen for transfer to ‘Hien ty’ (the office in charge of supervising all local affairs) for investigation and adjudication.”[10] Local mandarins who rallied troops and inhabitants without permission would be convicted of rebellion. Article 35 of “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” said: “Local rulers who mobilize troops and inhabitants without a royal decree shall be convicted of attempted rebellion...”[11]

That the state attached importance to building, mobilizing and commanding the army completely eliminated the possibility for aristocrats to build their own armies as previously or to rally forces for ruling as feuds in localities. Even the state army was organized and placed the unified command in the central court. While strengthening the military forces in localities, Le Thanh Tong wanted to restrict the powers of army generals. So, he divided the country into 13 “dao” (provinces) and established in each “dao” three administration offices, including “do ty” in charge of military affairs with three military mandarins “tong binh”, “tong binh thien su” and “tong binh dong tri” representing the central state to hold the military powers in each “dao”. Besides, the king intensified the suppression of rebellions, especially those in border regions with the aid of foreign forces in the west, the north and the south. Moreover, the royal court managed more strictly ethnic minority mandarins in remote border areas by appointing reliable mandarins from delta areas to rule critical border regions and ordering local minority mandarins to strictly abide by royal regulations and ceremonies. Despite being given more autonomy, local mandarins still submitted to the royal court’s oversight and could not have hereditary titles without approval of the royal court. In addition, Le Thanh Tong launched administrative reforms nationwide toward restricting the powers of local mandarins while associating the central administration more closely to localities. These reforms contributed to limiting the trend of ruling as feuds while preserving the unification and concentration of power into the royal court.

Protecting the national territory by law

In order to avert the danger of foreign invasion and domestic rebellions, Le Thanh Tong attached importance to legal measures. The Hong Duc Code contained many articles reflecting the ideas, policies and measures on protection of the territorial sovereignty and national security. For instance, it established as crimes and imposed harsh penalties against many acts of infringing upon the territorial sovereignty, national economic sovereignty, such as fleeing abroad (Article 71); selling land to foreigners (Article 74); selling weapons and explosives to foreigners (Article 75); cutting down bamboo and timber trees to sabotage critical border areas (Article 76); attempted rebellion (Article 25); colluding with foreigners in disclosing state secrets (Article 79); border mandarins neglecting responsibility which causes serious damage to the national sovereignty and security (Article 613), and so on.

This reflects that Le Thanh Tong is the king who most strongly followed the ideology of the rule of law in the national construction and defense in the Early Le dynasty.-