Tran Hong Nhung

Lecturer

Hanoi Law University

Vietnam’s feudal state under the Nguyen dynasty (1802-1884) attached great importance to legislative work with a coherent and logical process from the drafting and transfer of legal documents, management and use of official seals, organization of archive work to the training and employment of paperwork staff. The Nguyen dynasty’s due attention to the drafting of legal documents contributed to the development of a strong public administration, serving as the basis for the attainment of significant achievements in various aspects of the country’s social life in this period. This also offered valuable lessons on the importance of the human factor, the clear definition of duties of each responsible individual, and the role of inspection and supervision in the process of formulating and promulgating legal documents, for today’s lawmaking work in Vietnam.

Types of legal documents under the Nguyen dynasty

The Nguyen dynasty’s rulers, from King Gia Long to King Tu Duc, attached special importance to lawmaking activities for various reasons. First, the country faced an economic decline and social instability after wars; hence, law became a necessary tool for re-stabilization of the situation. Second, the management of a vast territory required a unified legal system throughout the country for the protection of national sovereignty and territorial integrity and the reflection of ethnic diversity. Third, the constant economic development and expansion of social relations also required a corresponding legal development in order to build a strong nation against the danger of foreign invasions and to perform the state’s economic and social functions; regulations should be issued in time to cope with frequent national difficulties and instabilities.

Most prominent among the Nguyen dynasty’s legislative achievements was the emergence of a national code - “Hoang Viet Luat Le” (Royal Laws and Regulations of Vietnam), also known as the Gia Long Code. This was the most comprehensive code of Vietnam’s ancient laws. Together with codification efforts, the Nguyen dynasty’s legislators also paid attention to the systemization of separate legal documents into a number of large collections such as “Kham dinh Dai Nam dien su le” (Ancient Procedural Regulations of Great Vietnam)[1], “Dai Nam dien le toat yeu” (Brief ancient regulations of Great Vietnam)[2], and “Minh Menh chinh yeu” (Chronicles of Minh Menh)[3], which aimed to facilitate the application of law.

Besides, state management documents were also issued in a great volume, which were diverse in form and content, comprising documents under the king’s jurisdiction (laws, decrees, orders, directives….) and documents under the competence of state bodies at the central and local levels (reports, official letters, instructions,….), as well as books and registers in service of state management activities such as civil status books, land registers, mandarins’ personal records, financial books…[4].

It should be also mentioned a great volume of “huong uoc” (village conventions), which were considered “codes” to regulate major social relations within villages and communes. They were recognized and permitted for publication by the state according to separate regulations. With their distinctive characteristics, “huong uoc” further enriched the legal system, creating the identity of the politico-legal culture of feudal Vietnam.

Most legal documents of the Nguyen dynasty, which have been archived and preserved so far, are valuable, reflecting various aspects of the political, military, diplomatic, economic, cultural and social life of the last monarchy in Vietnam’s history, especially “Chau ban trieu Nguyen” (the wood carved documents of the Nguyen dynasty) recognized in 2014 by UNESCO as the documentary heritages in the Memory of the World Program for the Asian-Pacific region.

Each type of documents had to comply with certain clear regulations on promulgating competence, contents, and formulating, promulgating and archiving process.

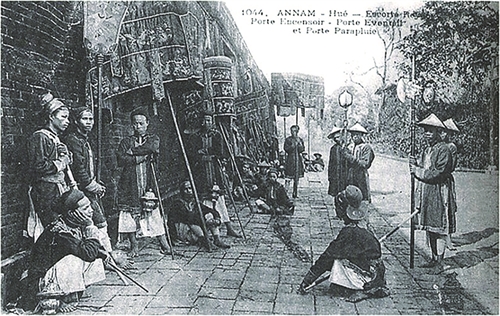

|

| Drafting legal documents under the Nguyen dynasty__Photo: Internet |

Legislative process under the Nguyen dynasty

Drafting and promulgating agencies

Under King Gia Long’s tenure (1802-1840), the archive, management of documents were assigned to three bodies, namely “Thi thu vien”, “Thi han vien” and “Noi han vien”, while “Ty thuong bao” was charged to keep official seals.

In his first reign year (1820), King Minh Menh merged these offices into “Van thu phong” which was charged to manage the delivery of clerical papers, decrees, orders and royal statements. In 1829, Minh Menh decreed to change “Van thu phong” into “Noi cac”[5].

“Noi cac” (Cabinet) was given specific functions: taking care of official seals; escorting the king in inspection tours or festivities; passing the king’s orders to yamen; collecting and copying official letters and reports to and from the king,… However, the service of official letters and reports to and from the king was performed by “Thong chinh su ty”[6], not by “Noi cac” which was also charged to check irrational books of yamen; record books, and dispatch them in royal examinations[7].

The Nguyen dynasty’s Cabinet existed for more than 100 years from 1829 to 1933 when King Bao Dai abolished it for establishment of “Ngu tien van phong” with the same functions. In addition to “Noi cac”, which directly assisted the king in clerical work, other offices also undertook administrative work, including “Han lam vien” tasked to draft diplomatic documents, conferment orders, decrees, orders, important statements of the state; “Ty buu chinh” in charge of delivery of official letters; “Ty thong chinh su” receiving reports, official letters and books of localities sent to the royal court; examining documents before transfer to “Ty buu chinh” for delivery to localities. The ministerial offices took charge of keeping official seals, receiving reports and official letters submitted by localities for transfer to various departments for implementation, and collecting documents to be submitted to the emperor for approval. Each agency was given clear functions and competence in order to ensure smooth paperwork and heighten the quality and enforcement effect of local documents.

Legal document-drafting, -promulgating, -transferring, -handling and -archiving process under the Nguyen dynasty

It can be realized through historical documents and laws that the Nguyen dynasty attached great importance to the drafting, promulgation, transfer, handling and archive of local documents.

In drafting, these documents had to comply with given forms of presentation, comprising the country’s name (for diplomatic documents), document title, promulgating body, recipients, names of document drafters, approvers, date of issue and seal of the promulgating body or individual. In 1838, after renaming the country as Dai Nam (Great Vietnam), King Minh Menh decreed that the inscription of the country’s name on documents was an important issue of national dignity and the country’s name of Dai Nam must be printed on all documents and papers[8]. At the same time, the document contents had to be presented with the standardized number of lines and words in each page and without tabooed names. “Hoang Viet Luat Le” set regulations to limit mistakes or errors in documents as follows:

- Addition or deletion of details and words in clerical papers shall be penalized with 60 strokes of beating with the heavy stick, or hard labor or exile if committing frauds in making additions or deletions (Article 69);

- Those who commit errors in re-writing clerical papers shall be penalized with 100 strokes of beating with the heavy stick (Article 322);

- Those mandarins who make reports with inconsistent contents shall be subject to hard labor or exile for serious violations.

The Nguyen rulers also set the following regulations on signing and stamping of legal documents:

- Before being submitted to responsible authorities for signing for promulgation, legal documents must be carefully examined by designated persons;

- For legal documents to be submitted to the king, in addition to the signatures of office heads or deputy-heads, the document drafters and examiners must write their names on the documents. These two mandarins shall bear joint liability for the contents of the submitted documents;

- Mandarins of the same yamon are forbidden to sign the documents in substitution; violators shall be punished[9].

In order to ensure the quick, safe and secret delivery of documents, the state clearly provided the modes, measures and time limits of delivery. According to the Nguyen dynasty’s regulations, those who were responsible for delivery of documents, including the king’s orders, had to protect them from disclosure, ruin or loss. Articles 60 and 61 of “Hoang Viet Luat Le” stated:“ Official letters and books of the king or yamon are important orders concerning public affairs to be disseminated to the entire population. If those who let them ruin or be stolen shall be penalized in accordance with law.”

In 1820, King Minh Menh established “Ty buu chinh” (Postal office) under “Bo Binh” (Ministry of Military Affairs) to take charge of the delivery of documents throughout the country. In 1834, he additionally set up “Ty thong chinh su” functioning to receive and distribute local documents sent to the royal court and examine official letters and papers of royal offices to be sent to localities. According to the Nguyen dynasty’s regulations, documents had to be put into sealed envelops, then tied up before being put into sealed bamboo pipes which had to be put into cloth bags for transportation. Secret documents had to be put into double bamboo pipes, one inside the other[10]. The state also clearly defined which offices would receive and submit which documents to the king for signing.

The state management documents, after being promulgated, and handled, were carefully arranged, preserved and archived for reference and compilation of royal historical records. King Minh Menh set up four offices attached to the cabinet to take care of official seals, draft and issued decrees, orders and directives; and to record and keep the king’s writings and poems. Therefore, the entire volume of important documents of the Nguyen royal court had been archived in these offices until 1945. Apart from the cabinet’s library, King Minh Menh established some others such as “Tang thu lau” built in 1825 on an islet in the middle of Hoc Hai lake in the imperial city of Hue for storage of the king’s books and documents, where the whole volume of the valuable land registers were kept until the end of the Nguyen dynasty; or “thu vien tu khue” where numerous valuable books were kept. The Nguyen kings after Kings Gia Long and Minh Menh also set up various libraries, including “Thu vien quoc su quan” established in 1841 by King Thieu Tri, “Tan thu vien” by King Duy Tan (1907-1916), and “Thu vien co hoc” in 1922 by King Khai Dinh.

The feudal rulers under the Nguyen dynasty set a system of strict regulations and processes for the drafting of legal documents and their contents, their promulgating jurisdiction, delivery, handling and archive, the management and use of officials seals and the training and recruitment of clerical staffs. These regulations aim to ensure the quality and effect of legal documents. Thanks to the Nguyen dynasty’s attention paid to the compilation, preservation and archive of documents, a large section of state management documents, administrative books, including 800 volumes of documents, 11,000 land registers, over 31,000 wood carved documents and huge collections of other valuable documents have been preserved until today[11]. This contributed to the building of a strong and effective public administration serving as the basis for the attainment of important achievements under the Nguyen dynasty.-

* This article is translated from the Vietnamese version published on Hanoi Law Review, issue No. 10 of 2019.