Dr. Pham Thi Ngoc Thu

History Faculty, Social Sciences and Humanities School, Ho Chi Minh City State University

Associate Prof. Dr. Nguyen Duy Binh

History Faculty, Hanoi Pedagogical University

MSc. Huynh Ba Loc

History Faculty, Social Sciences and Humanities School, Ho Chi Minh City State University

The Nguyen dynasty (1802-1884) managed the society by law through the administrations at different levels. Besides, the Nguyen kings were also fully aware that for villages and communes, village conventions played an important role as manifested in the popular saying “Phep vua thua le lang” (the king’s laws comes after the village’s customs). Village customs were customary practices in daily life and production upheld and orally passed from generation to generation by villagers while village conventions were customs and practices documented in paper or carved in stone or wood. The village customs and practices defined in village conventions were specific norms in various aspects of social life to be voluntarily followed by all community members. The state sought ways to use village conventions as a means to enforce state laws in social life. This helped establish the relationship between state laws and village conventions as well as customs, that of complementation, contradiction and conflict.

Under the Nguyen dynasty, the conventions of northern villages were rich and diverse. Analyzing the collected village conventions, we can describe the relationship between state laws and village codes as well as customs as follows:

First, the Nguyen rulers permitted villages to preserve their own customs and practices while strictly controlling the making of village conventions by ridding of heavy, illegal and impractical provisions in order to intervene in the village life.

Village conventions determined the responsibilities, obligations and interests of villagers in various aspects of life. They generally contained provisions on social organization and village mandarins; New Year celebrations; rituals to worship village deities; land, tax, military conscription; agricultural and irrigation extension; cultivation and husbandry protection, environmental protection; wedding and funeral ceremonies; immigration and registration, learning encouragement, penalties against robbers, fire fighting. Village conventions also addressed the relations between individuals and communities and social organizations, depending on circumstances, conditions, customs, life and intellectual levels of inhabitants.

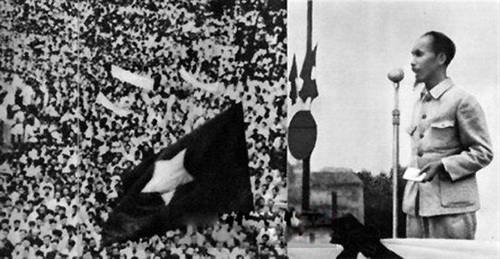

|

| Soldiers of the Nguyen dynasty__Photo: Internet |

King Gia Long attached great importance to issuing regulations in villages and communes and building codes of conduct applicable to localities. Although the state respected the autonomy of villages and communes, it applied state laws and controlled local customs and practices in order to intervene in village and commune affairs.

So did King Minh Mang, who decreed after his inspection tours of northern provinces: “Wedding and funeral ceremonies shall follow local customs and practices while lawsuits shall be settled in accordance with state laws”[1].

The village management policy was a combination of customs and state laws. Such important national affairs as protection of administration, order and security, land ownership, taxation, public labor, military conscription were handled under the state laws while daily events such as marriages, funerals, worship… must observe local customs and practices.

Second, village conventions and customs constituted a supplemental source of law, facilitating the enforcement of state laws in the social life of villages and communes.

In addition to laws, the feudal state introduced codes of conduct, aiming to regulate important social relations according to the will of the ruling class and to use the existing customs and practices as a supplemental source of law. The selected social rules were customary regulations on morality, religion, marriage and family and cultural activities, which were deeply rooted in the social life and voluntarily observed by villagers. As village customs and practices originated from social norms, the relationship between state laws and village conventions and customs was in essence close.

A French scholar considered villages and communes as “separate entities of a country or other countries within a nation”[2]. In reality, people living in villages only knew the villages where they lived and witnessed daily occurrences. With such in mind, people in some villages paid more heed to village customs and practices than to state laws. In the management of villages and communes, the state managed people indirectly through the Council of Village Mandarins which acted as a bridge for adjudication of law offenders. Therefore, “village regulations must be framed within the state laws, be approved or rejected by superior mandarins”[3]. This could be considered the most appropriate solution for strict and effective management of villages and communes in a closed mechanism which existed for ages in Vietnamese villages. Recognizing villages and their customs as the foundations for making state laws, the feudal state incorporated in village codes its ideologies and powers through specific provisions on such social relations as marriage and family, village ties.

The state also incorporated some provisions of village conventions in state laws or regulations. Village rules were acknowledged and incorporated in laws by the royal court. For instance, a village regulation that “those who clandestinely slaughtered their horses or buffaloes shall be punished with 100 strokes of wooden stick and all meat, bones and skins of the slaughtered animals shall be given up to mandarins”, which aimed to protect agricultural production, was codified in Hoang Viet Luat Le (The Royal Laws and Regulations of Vietnam)[4].

The feudal state always advocated to rely on fine customs and practices in villages to reward and encourage people. For instance, the Nguyen kings conferred different ranks to villagers aged 70 or older; rewarded children who showed filial piety to their parents and grandparents; or even built shrines to worship faithful women. King Minh Mang once decreed: “From now on, local mandarins must find people aged 100 or older, people who are dutiful to their parents or who are honest returning dropped items to their owners and report them to local mandarins, then to Bo Le (the Ministry of Education, Culture and Health) for commendation.”[5]

Another example is that Clause 65 of the village code of Phu Xa Doai commune, Kim Anh district, Vinh Phuc province, which provided that such public labor as canal digging, dike construction for agricultural production must be performed by farming households without any exception[6], was incorporated in Hoang Viet Luat Le.

So, the village conventions and state laws were closely inter-related and complementary in the direction that village conventions must conform to and detail state laws.

Third, the state led the making of village conventions. Though relying on village conventions, the state took the initiative in establishing the close relationship between state laws and village conventions as well as in appointing villagers to oversee the issuance of village regulations. The state set criteria of village convention drafters and issued forms of presentation and ways of adopting village regulations, and punished village chiefs or deputy-chiefs who violated village regulations.

King Gia Long’s decree on village conventions in northern Vietnam addressed such important events in villages and communes as festivities, celebrations, weddings, funerals, deity worshipping, permitting the preservation of fine customs and practices while abolishing bad ones.

Fourth, the state established the legal association of state laws with village conventions, aiming to raising the effectiveness of social management and the legality of village conventions through such measures as permitting village conventions to concretize state laws or incorporating village regulations in state laws.

The norms set out in village conventions were simpler but more specific than provisions of state laws. Village conventions dealt with specific cases to enforce state laws. Hoang Viet Luat Le and other laws of the Nguyen dynasty prescribed heavier penalties for serious offenses while village conventions provided lighter ones against minor offenses as seen in their provisions on military conscription, funerals, etc.

So, the following remarks can be drawn from the above analysis:

First, as the Nguyen dynasty was deeply aware of villagers’ thinking that “the village comes into being before the state” or “the village is near while the state is far away” and both state laws and village conventions originated partly from customs and practices, it continued to respect the autonomy of villages and communes. It can be said that in the Vietnamese traditional society, people were inclined to customary rules rather than to state laws. Hence, the state only needed villages to pay enough taxes and recruit sufficient draftees and public laborers while permitting them to manage other social relations and aspects of social life. However, the state still created mechanisms to appoint and manage its representatives in villages.

Second, the Nguyen dynasty incrementally incorporated its authority and Confucian ideology in village conventions as clearly seen in village regulations on social relations, marriages and funerals, parent-child or spousal relationship, male-female relations…. This aimed to ensure the conformity of interests between the state and the village.

Third, the Nguyen dynasty controlled the drafting of village conventions through a village institution. It set criteria of village convention drafters and standards for village conventions. So, village convention became an important instrument helping the state control its villages and communes.

Fourth, the Nguyen dynasty adopted its policies in coordination with the village management body and village conventions to ensure effective national administration and management. This in fact brought about positive results, bringing villages and communes into the orbit of royal management.

However, the royal court could not fully control villages and communes. “Hoi dong ky muc” (the Council of Notable Village Elders) remained to be a major force in villages having a decisive say in almost all village affairs. Through this institution, villages might quickly and easily react when the state enforced a policy which they deem infringing upon their interests.-