Tran Hong Nhung LL.D.

Hanoi Law University

The Nguyen dynasty (1802-1884) was often recalled for its strong determination to fight corruption through resolute, strict and clear measures, which served as an effective tool to deter and educate the public as well as to prevent and restrict embezzlement and corruption.

In 207 corruption cases recorded in “Dai Nam thuc luc” (Chronicles of Great Vietnam), a 10-volume authentic history book, the Nguyen rulers applied various punitive measures against such crime, which can be classified into criminal and administrative ones.

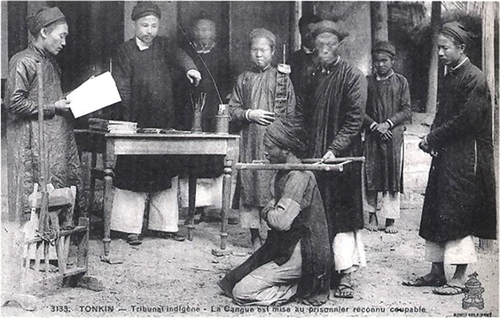

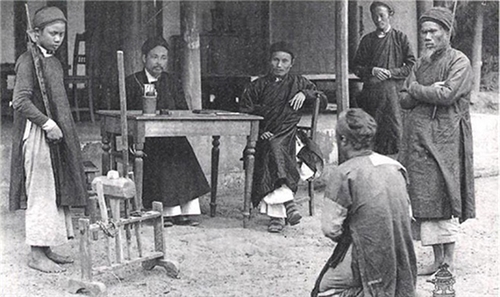

|

| A court hearing under the Nguyen dynasty__Photo: Internet |

Criminal measures

Prominent among criminal measures were “ngu hinh” (five criminal penalties), including:

(i) “Xuy hinh”: Whipping with a small rod rattan about three meters long with nods cut off;

(ii) “Truong hinh”: Whipping with a large rattan stick over three meters long with all thorny nods retained;

(iii) “Do hinh”: Penal servitude;

(iv) “Luu hinh”: Exile to a remote location for hard labor; and,

(v) “Tu hinh”: The death penalty, which was executed through “tram” (beheading), “giao” (hanging); “khieu” (beheading then abandonment of the head in a public area) or “lang tri” (amputating the hands and feet and slow slicing).

The first four measures could be imposed independently or along with others, depending on the severity of offenses.

In addition to “ngu hinh”, other punitive forms such as tattooing on the face or forehead with indelible ink, fettering their feet in cell, enslaving their wives or daughters as servants, were also applied by feudal rulers.

Over 80 percent of the corruption cases were criminally handled, which demonstrates the feudal state’s stern attitude toward such social evil. The Nguyen dynasty’s kings advocated the death sentence as an effective instrument to suppress the crime.

In his 1832 decree, King Minh Menh stated: “Ancient rulers made law to punish crimes in order not to punish more, to kill offenders in order not to kill more…. if we now decline to penalize crimes and kill offenders, later more crimes will come and offenders will be numerous then we will not be able to kill all…. We want to punish offenders to prevent crimes. If a piece of a person’s skull could save thousands of others from misery, such penalty will continue to apply though it is merciless” (Dai Nam thuc luc, volume 2, p. 299).

In 1818, King Gia Long sentenced Phan Tien Quy, a corrupted mandarin, to strangulation. He said: “Quy has abused his position to embezzle public funds and exploit people. His sins were untold and he cannot escape punishment”. The corrupted mandarin was strangled and his execution was publicly notified in all districts (Ibid, vol.1, p. 976).

In 1822, Nguyen But, a mandarin of the Ministry of Construction, counterfeited royal seals to take rice from the state warehouse. His sin was uncovered and King Minh Menh ordered his beheading right at a public market (Ibid. vol.2, p. 189). He also sentenced to death a storekeeper named Tran Cong Trung who harassed for bribes, and another storekeeper who falsely measured storehouse paddy.

King Tu Duc was also known for his resolute fight against corruption and bribery. He himself once ordered the beheading of a storekeeper who was caught red handed while stealing public money.

Criminal measures were also applied to courtiers with meritorious services or even royal relatives who breached state laws. For instance, Ton That Dieu and Ton Tat Bieu, royal family members, were sentenced to hanging for fraudulently swapping worship articles at The Mieu (royal temple). Minister of Military Affairs Dang Tran Thuong who counterfeited a royal honor-conferring decree and misappropriated a public lake and land or Deputy Minister of Finance Tran Nhat Vinh who took bribes and appropriated other people’s property were also subject to capital punishment.

Under the Nguyen dynasty, four cases involving royal relatives, 12 cases related to high-ranking mandarins, and 25 cases of corruption committed by provincial chiefs were put on trial with severe penalties even when these mandarins had been relieved from positions. In 1835, Le Van Duyet, chief of Gia Dinh citadel, was charged with seven serious crimes and sentenced to beheading and his property was confiscated. In March 1834, provincial chief Tran Duong was detected as having embezzled more than 1,000 quan (a feudal currency unit) was sentenced to hanging.

In addition to the death penalty, the Nguyen kings also applied other punitive measures such as “xuy”, “truong”, “do”, “luu”, hand and foot amputation, fettering, face tattooing, etc., to offenders.

The application of severe penalties, including capital punishment, by the Nguyen feudal rulers proved to be necessary under the then circumstance that a large section of mandarins at all levels ignored the state law. Such measures aimed to eliminate dangerous elements from the society and deter crime commission and remission.

Administrative and disciplinary measures

Under the Nguyen dynasty, all offenses were subject to liability examination and punishment. In addition to criminal measures, a system of administrative and disciplinary measures was also applied. Offenders might be subject to salary cut, bonus subtraction, demotion, dismissal, property confiscation, and material compensation.

The administrative and disciplinary measures against corruption were fairly common in the Nguyen dynasty, which were usually applied together with criminal measures or independently if the cases were not so serious.

It was recorded in ‘Dai Nam thuc luc’ that administrative measures mostly applied by Kings Gia Long, Minh Menh, Thieu Tri and Tu Duc were relief from position, demotion or dismissal (83 cases), then property confiscation (11 cases), material compensation (9 cases), and bonus subtraction (2 cases).

Especially, three cases were pardoned by King Minh Menh as the offenders honestly reported their wrongdoings and redeemed their past. Those were the case of Le Chat, chief of Bac Thanh province, in 1823, who had embezzled 3,800 quan and 800 baskets of paddy; or case of Dien Khanh Cong Tan in 1831, who allowed a merchant to falsely declare his boat as tax-free for tax exemption; or governor of Son Tay province in 1839 honestly reported his sin of harassment for bribe.

In 1840, King Minh Menh decreed: “Everyone makes mistakes. The state shall forgive it provided that he confesses his sin. Within 15 days after the promulgation of this decree, those who fail to abide by the state law and committed offenses have to honestly report their wrongdoings for pardon. If not, they will be severely punished”. (Dai Nam thuc luc, vol. 5., p. 657).

Consequently, governor general of Son Tay, Hung Yen and Tuyen Quang Nguyen Cong Hoan and criminal judge of Son Tay province Vu Vinh honestly reported their bribe-taking acts. Both were reprimanded then pardoned by the king. The bribed property was confiscated to public funds.

The application of punitive measures against corruption under the Nguyen dynasty shows that various kings from Gia Long to Tu Duc attached special importance to punishing the crime of corruption. Criminal measures, particularly severe penalties, had a great deterrent effect in limiting corruption. Meanwhile, the administrative and disciplinary measures demonstrated the attitude of the feudal state as well as its kings to resolutely punish the offenders regardless of their positions or social class.-