Tran Hong Nhung LL.D.

Hanoi Law University

In Vietnam’s feudal regime, the vulnerable included women, the elderly, children, persons with disabilities, widows, widowers, the lonely, ethnic minorities, persons with nobody to rely on, prisoners and, in a broader sense, people in general as commoners in relation to the state. The feudal states paid attention to these disadvantaged groups and protected their legitimate rights and interests. The human rights then were understood in a narrow sense as legitimate needs and interests of people, which were recognized and protected to a certain extent by law.

Legal provisions on protection of women’s rights

During Vietnam’s feudal time, Confucianism was the prevailing ideological system with prominence given to the patriarchy. Hence, women occupied an inferior role and position in families as well as the society as compared to men. Confucian ideologies, ceremonies and virtues were institutionalized in various laws prescribing women’s duties as well as imposing harsh penalties against them. However, being influenced by the traditional wet rice-farming culture that respected women, Vietnamese feudal legislators recognized and protected a number of their rights and interests as demonstrated in legal texts from the state laws to “huong uoc” (village conventions).

The criminal law, albeit characterized with a system of severe penalties[1], still demonstrated a humane spirit toward the disadvantaged in society, including women. Article 1 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat (Criminal Law of the Royal Court) of the late Le dynasty provided: “Truong hinh (criminal penalty of beating with a heavy stick) can be applied either together with other penalties as “luu” (exile), “do” (hard labor) and “biem chuc” (rank demotion) or independently, but only to men”. The law imposed lighter penalties for female offenders. For example, women who were subject to “do” (hard labor) would be given jobs less heavy than those given to male offenders. For a number of offences, female offenders were subject to lighter penalties. Article 429 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat stated: “Female servants who commit stealth shall be sentenced to less severe punishment”. Article 441 of this Code also provided: “Trespassers into other people’s gardens shall be sentenced to “biem”; female trespassers shall be sentenced to one-grade mitigation”.

Regarding judgment enforcement, the law also provided: “Female offenders who are sentenced to death or rod whipping while being pregnant shall have their judgments delayed for 100 days after their childbirths” (Article 680 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat) or “female offenders shall not be detained if they are sentenced to “luu” or lighter judgments” (Hoang Viet Luat Le - the Royal Laws and Regulations of Vietnam).

In the marriage and family field, feudal laws recognized and protected a number of women’s personal rights such as the right to break off their engagement in case their fiancés suffer a grave ailment, commit a crime or go bankrupt (Article 322 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat); the right to request divorce if their husbands neglect intimate relations with them for five months or for one year if the wives already had children (Article 308 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat) or sons-in-law absurdly lash out at their parents-in-law (Article 333 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat), or their husbands go missing or run away for three years (Article 108 of Hoang Viet Luat Le); or the right to remarry after their divorce (Article 108 of Hoang Viet Luat Le). Under feudal laws, women were also entitled to own their personal and common property in their marriage. Property sale, transfer, mortgage or donation contracts recorded in “Quoc Trieu Thu Khe The Thuc” (Royal Contract Procedures) had to be signed by both husband and wife. The feudal laws gave prominence to the assignment of heritances to sons and nephews to worship ancestors but also recognized the eldest daughters’ right to heritances (Article 391 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat) or the wives’ right to enjoy heritances in case the husbands die without common children (Articles 375 and 376 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat), or daughters were given equal heritances like sons.

In addition, acts of infringing upon the honor, dignity, health or lives of women would be severely punished. For acts of seducing young girls, Article 402 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat prescribed: “The seducers shall be charged with fornication and pay fines; the brokers shall be sentenced to “do” (hard labor) or “luu”. For acts of raping, Article 403 provided: “The offenders shall be sentenced to exile or death and pay fines greater than that paid for fornication. If the victims are raped to death, the offenders’ real and personal estates will be confiscated as payment to the victims’ relatives”.

Hoang Viet Luat Le of the Nguyen dynasty devoted a whole chapter with nine articles defining such crimes as well as offenders, with the penalty of “giao” (hanging) or “tram” (beheading) imposed on those who committed “cuong gian” (raping) or “luan gian” (collective raping). It also protected women in other cases by providing that those who committed such acts as snatching property of girls or women on the street, or kidnapping them for sale or forced labor would all be sentenced to “tram” (beheading) and their accomplices to “giao giam hau” (hanging but detained until appeal trial).[2]

Not only state laws but also traditional customs and practices in villages protected women’s rights. The village convention of Phu Khe, Phu Tho province (made in 1789) provided: “Those who rely on a large number of brothers and children to suppress solitary persons, to maltreat or tread on the neck of widows will be subject to a fine of 30 “quan tien” (an ancient unit of currency) and 30 rod whippings”. The village convention of Quang Nap commune, Ninh Binh province, emerging in 1795, provided: “Real and personal estates shall be divided into ten portions, one portion shall be used as the cult-portion field and the remainder shall be equally divided to all inheritors, male and female”[3].

Despite all Confucian prejudices against women, Vietnam’s feudal laws, although declining to recognize gender equality, more or less acknowledged a number of personal and property rights of women. This revealed a fairly progressive and humanitarian approach taken by feudal legislators.

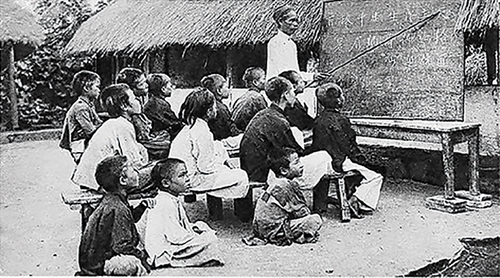

|

| A class in the feudal time__Photo: Internet |

Provisions on protection of interests of the elderly, children, persons with disabilities and ethnic minority people

Feudal laws exempted or reduced penalties against the elderly, children, persons with disabilities and ethnic minority people when they committed a number of offences. This was clearly provided in Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat as well as Hoang Viet Luat Le.

According to Article 16 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat, people aged 70 or over, children aged 15 or under, who were subject to exile or lighter judgments, were allowed to bail out. People aged 80 or over, children aged 10 or under, or suffering a dangerous disease, who committed treason or murder liable to death sentence, shall have their cases reported to the king for decision; if they committed burglary or attacked other persons, they would be allowed to bail out. Persons aged 90 or over and children aged 7 or under would not be executed even if they deserved death sentence.

Article 17 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat prescribed the application of law in favor of the elderly and children: Persons who committed crimes at younger ages and were detected only when they get old and/or disabled would be adjudicated under the law on the elderly and persons with disabilities. This also applies when they turn old and disabled at their places of exile. If persons committed offenses when young and their crimes were detected only when they grew up, they would be adjudicated under the law on minor.

Article 665 of the same code defined: Mitigation-eligible offenders such as persons aged 70 or over, children aged 15 or under and persons with disabilities may not be tortured; their crimes would be decided upon declarations of witnesses.

The law under the Le dynasty also protected young girls by providing those who had sexual intercourses with girls aged under 12, even with the latter’s consent, would be convicted of raping.

For ethnic minority people, Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat recognized their own customs and practices. Article 40 stated: “Ethnic minority persons commit offences against one another shall be adjudicated under their customs and practices. If ethnic minorities commit crimes against ethnic majorities, they shall be adjudicated according to the state laws”. Article 164 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat protected the interests of ethnic minority people as it severely punished mandarins for acts of treading upon their neck or groundlessly arresting them.

Provisions on protection of disadvantaged people, prisoners and servants

Widowers, widows, orphans, cripples, poor people without relatives to rely on, the lonely and spinsters were protected and cared for by law. Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat provided: “If there are in royal capital, wards, street alleys, villages and hamlets sick persons who have no one to nurture, lying by the roads, bridges, watch posts, pagodas or provincial towns, local mandarins shall build tents for them to stay in, take care of them, give them food and medicines, and must not leave them in lament and misery. In case of death, it must be reported to superior mandarins and the victims shall be buried according to local conditions, without leaving their corpses exposed under the sun. Those local mandarins who failed to abide by this order shall be subject to “biem”. If sick persons come to stay in pagodas, the residing Buddhist dignitaries who fail to report thereon to mandarins and nurture them at their own will shall also be penalized” (Article 294) or “for widowers, widows, orphans, cripples and poor people without relatives to rely on, who cannot support themselves, local mandarins shall gather and nurture them” (Article 295).

For people who were struck by natural calamities, droughts, floods, epidemics, crop failures and famines, the state adopted relief policies, building relief storehouses, distribution of rice, exemption or reduction of taxes. The Nguyen dynasty law defined mandarins’ liability to help people upon natural disasters, foreign invasions…, providing: “If such natural disasters as floods, droughts… occur in any locality, local mandarins shall examine and fully report thereon so that the royal court considers tax exemption and food supply…. If inhabitants living by rivers, sea, lakes and ponds are suddenly hit by floods or inundations, local mandarins shall, on one hand, report them to superior mandarins and, on the other hand, visit the sites to inspect the situation for relief without delay”[4].

For prisoners, the feudal state adopted humanitarian policies. Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu (A Complete History of Great Vietnam) recorded: It was bitter cold in winter October, the king (Ly Thanh Tong) said to court mandarins: I stay in the royal palace with heaters and warm clothing but still feel so cold. Thinking of prisoners who are interned in jails without enough food to eat and clothes to wear or may die I feel compassion for them and thereby order mandarins to supply them with blankets, mats and two meals a day”[5]. In addition, the law severely punished acts of corporal punishment of prisoners (Article 658 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat), and provided “prisoners shall be given health care and medical treatment” (Article 663 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat)….

To protect servants, the law provided: “Those who deliberately detain servants already released as free citizens with certificates and coerce them to toil as servants shall be punished with 50 rod whippings and one-grade demotion” (Article 491 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat).

So, it can be realized that the protection of human rights, civic rights, and rights of disadvantaged people was acknowledged by various feudal dynasties as they attached great importance to and legalized such rights.-