Tran Hong Nhung LL.D.

Hanoi Law University

Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat (The National Criminal Code - the Code) of the Le dynasty (1428-1527) was the culmination of legislative work in feudal Vietnam. With 722 articles arranged in 13 chapters, it dealt with almost all basic social relations then, from criminal, marriage-family, inheritance, contractual, procedural, and land to administrative issues.

As land became a main means of production and the most valuable asset of each family under the feudal regime, the Le dynasty attached special importance to regulating this relation. Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat devoted a whole chapter titled “Dien San” (Real and Personal Estate) with a total number of 56 articles listing specific land-related violations and corresponding punitive forms.

General punitive forms in Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat

The Code spelt out various punitive forms against violations in different areas, both criminal and civil.

“Ngu hinh” (five criminal penalties), which were meted out in Article 1, aiming to enhance deterrence. They were imposed corresponding to the severity of violations, including “xuy” (cane whipping); “truong” (lashing - with a heavy wood stick, for male offenders, or a bamboo cane, for female offenders); “do” (hard labor); “luu” (exile to a remote location); “tu” (execution by hanging or beheading), and “lang tri” (slow slicing an offender’s body until death).

Apart from the above-listed five criminal penalties, the Code prescribed other punitive forms, including:

- Rank degrading: The feudal state conferred on aristocrats and mandarins titles of 24 ranks. Offending mandarins subject to rank degrading would also have their salaries lowered. According to Article 27 of the Code, this penalty was applied at five levels, one-, two-, three-, four- or five-rank degrading. In addition to rank degrading and salary lowering, offending mandarins would also have their land-related bonuses slashed off. Through this, the feudal state partially revoked bonuses granted to mandarins with a view to heightening their sense of responsibility and performance. So, rank degrading not only reduced incomes but also greatly impacted the career, honor and prestige of offending mandarins;

- Demotion or dismissal from office, which was usually applied to mandarins who committed criminal offenses;

- Fine, applicable to corruption and burglary;

- Confiscation of the whole or part of property, applicable to corruption and burglar; and

- Letter tattooing, applicable to offenders sentenced to hard labor or exile to a remote location. Article 9 of the Code stated: “Persons sentenced to hard labor shall have their necks tattooed with two or four letters; offenders subject to exile to a remote location shall have their faces tattooed with six letters (for deportees to nearby areas), eight letters (for deportees to outskirt districts) or 10 letters (for deportees to remote areas).”

Unlike the present-day law under which penalties are applicable only to socially dangerous acts (crimes), the ancient law used them as universal measures applicable to almost all violations in all areas. Moreover, the present-day law prescribes a frame of penalties for each type of offenses so that judges may choose due punishment for every specific offense, while the ancient law prescribed in detail each penalty for every specific offense.

Land-related sanctions in Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat

Provisions relating to inherited land: Feudal legislators did not prescribe remedies for provisions on land inheritance but only anticipated circumstances which might occur in reality and guided in detail the heritance division. Punitive measures were applied only to illegal division of cult-portion rice fields, mainly with lashing or rank degrading

Provisions on land under the ownership of various subjects: Under these provisions, land was classified into public land and private land. With regard to private land, feudal legislators divided it into cultivation land and graveyard land.

The feudal state of the Le dynasty protected the ownership of all subjects, preventing acts of infringement upon public land and acts of coercive appropriation of private land. Specific penalties were meted out for specific violations. The Code provided: “Those who sell their allotted or portion land will be penalized with 60 lashes and two-rank degrading; the contract makers and witnesses shall all be penalized with the same penalties but at a lower level; the money earned from the sale and the land shall be confiscated into public coffers. Those who pledge such land shall be punished with 60 lashes and compelled to redeem such land” (Article 342). “Those who appropriate public land in excess of the prescribed quotas by one “mau” (equivalent to 3,600 m2) or over shall be punished with 80 lashes, by 10 mau with three-rank degrading, and all the proceeds from such land shall be confiscated into public fund. If they reclaim the waste virgin land, they shall not be penalized.” (Article 343). “Those who purchase land of other people by treading upon their necks shall be degraded by two ranks but allowed to get back their money” (Article 355).

The Vietnamese ancient law in the 15th-18th centuries also clearly provided: “Those who deceitfully claim relatives of someone or collude with others in land appropriation with village chiefs’ connivance shall all be punished by law, and the appropriated land must be returned to eligible subjects as prescribed by law. Those who nonsensically claim land of other people shall be punished with 60 lashes or one-rank degrading.

Major penalties applicable to this group of violations are rank degrading, lashing and exile to a remote location, together with measures to address the consequences or compensations.

Provisions relating to state management of land: Major punitive forms prescribed here were degrading, lashing, hard labor and exile to a remote location. Under these provisions, mandarins who committed acts of encroaching upon public ownership would have to pay compensations two or three times higher than the damages caused (Articles 345, 346 and 347). If provincial, district and commune mandarins let the already allotted land lie derelict, they must compensate for the proceeds there from; if the land was already allotted and yielded fruits, but they reported as deserted land for self-seeking with the proceeds from such land, they must pay compensations doubling the proceeds value into the state budget (Article 347). So, in the division of public land, if mandarins abused their powers for self-seeking, appropriating public property (proceeds), they would be subject to criminal as well as economic penalties. The principle of higher compensations was defined in Article 28 of the Code: “Compensations for material evidences shall double (the material evidences of public property); five times higher than the material evidences of serious offenses; nine times higher (for case of deliberate relapse into crimes)”. The application of this principle to offending mandarins contributed to preventing and deterring them from bullying and harassment of commoners.

Provisions relating to sovereignty protection: Article 74 of the Code provided: “Those who sell national land to foreigners shall be sentenced to death by beheading, the highest penalty.”

Provisions relating to land contracts: The provisions of Articles 383, 384 and 385 of the Code on land contracts contributed to the protection of the ownership of land of eligible subjects, creating legal basis for settlement of disputes.

In short, the above legal provisions of the Le dynasty contributed not only to guaranteeing the legitimate rights and interests of people in the countryside and the local stability but also to strengthening the state control over rural villages and limiting the illegal appropriation by village tyrants of public land as well as private land of local inhabitants. They prove to be helpful for the current judicial reform as well as the current process of building the socialist law-ruled state of the people, by the people and for the people in Vietnam in general and the upcoming revision of its Land Law as well as other relevant laws.-

Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat (The National Criminal Code - the Code) of the Le dynasty (1428-1527) was the culmination of legislative work in feudal Vietnam. With 722 articles arranged in 13 chapters, it dealt with almost all basic social relations then, from criminal, marriage-family, inheritance, contractual, procedural, and land to administrative issues.

As land became a main means of production and the most valuable asset of each family under the feudal regime, the Le dynasty attached special importance to regulating this relation. Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat devoted a whole chapter titled “Dien San” (Real and Personal Estate) with a total number of 56 articles listing specific land-related violations and corresponding punitive forms.

General punitive forms in Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat

The Code spelt out various punitive forms against violations in different areas, both criminal and civil.

“Ngu hinh” (five criminal penalties), which were meted out in Article 1, aiming to enhance deterrence. They were imposed corresponding to the severity of violations, including “xuy” (cane whipping); “truong” (lashing - with a heavy wood stick, for male offenders, or a bamboo cane, for female offenders); “do” (hard labor); “luu” (exile to a remote location); “tu” (execution by hanging or beheading), and “lang tri” (slow slicing an offender’s body until death).

Apart from the above-listed five criminal penalties, the Code prescribed other punitive forms, including:

- Rank degrading: The feudal state conferred on aristocrats and mandarins titles of 24 ranks. Offending mandarins subject to rank degrading would also have their salaries lowered. According to Article 27 of the Code, this penalty was applied at five levels, one-, two-, three-, four- or five-rank degrading. In addition to rank degrading and salary lowering, offending mandarins would also have their land-related bonuses slashed off. Through this, the feudal state partially revoked bonuses granted to mandarins with a view to heightening their sense of responsibility and performance. So, rank degrading not only reduced incomes but also greatly impacted the career, honor and prestige of offending mandarins;

- Demotion or dismissal from office, which was usually applied to mandarins who committed criminal offenses;

- Fine, applicable to corruption and burglary;

- Confiscation of the whole or part of property, applicable to corruption and burglar; and

- Letter tattooing, applicable to offenders sentenced to hard labor or exile to a remote location. Article 9 of the Code stated: “Persons sentenced to hard labor shall have their necks tattooed with two or four letters; offenders subject to exile to a remote location shall have their faces tattooed with six letters (for deportees to nearby areas), eight letters (for deportees to outskirt districts) or 10 letters (for deportees to remote areas).”

Unlike the present-day law under which penalties are applicable only to socially dangerous acts (crimes), the ancient law used them as universal measures applicable to almost all violations in all areas. Moreover, the present-day law prescribes a frame of penalties for each type of offenses so that judges may choose due punishment for every specific offense, while the ancient law prescribed in detail each penalty for every specific offense.

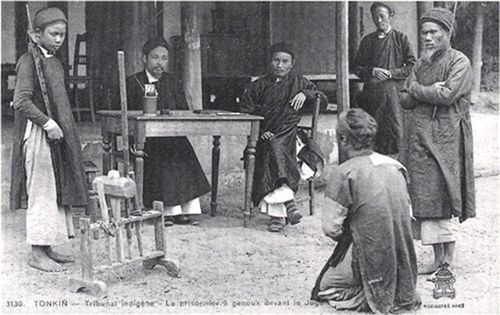

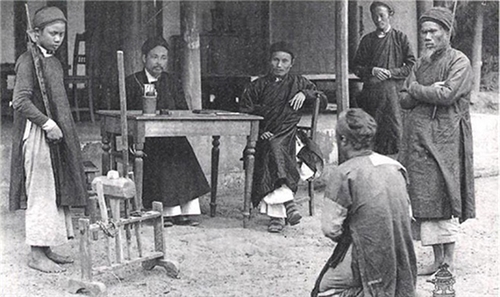

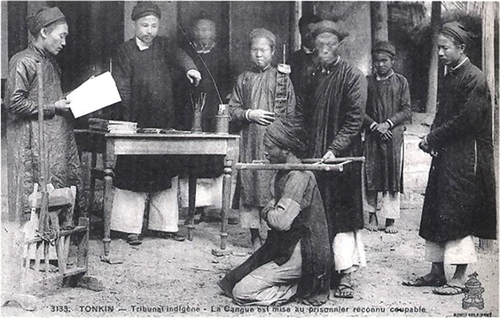

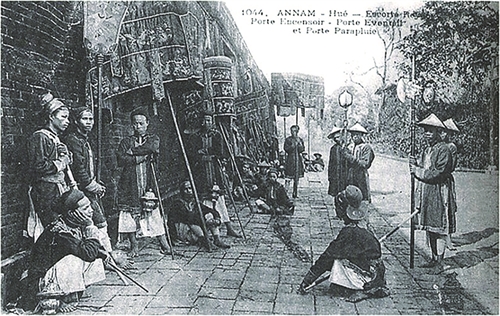

|

Reviving the scene of escorting offenders sentenced to dealth to the execution ground in the Early Le dynasty (1428-1527)__Photo: Internet |

Land-related sanctions in Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat

Provisions relating to inherited land: Feudal legislators did not prescribe remedies for provisions on land inheritance but only anticipated circumstances which might occur in reality and guided in detail the heritance division. Punitive measures were applied only to illegal division of cult-portion rice fields, mainly with lashing or rank degrading

Provisions on land under the ownership of various subjects: Under these provisions, land was classified into public land and private land. With regard to private land, feudal legislators divided it into cultivation land and graveyard land.

The feudal state of the Le dynasty protected the ownership of all subjects, preventing acts of infringement upon public land and acts of coercive appropriation of private land. Specific penalties were meted out for specific violations. The Code provided: “Those who sell their allotted or portion land will be penalized with 60 lashes and two-rank degrading; the contract makers and witnesses shall all be penalized with the same penalties but at a lower level; the money earned from the sale and the land shall be confiscated into public coffers. Those who pledge such land shall be punished with 60 lashes and compelled to redeem such land” (Article 342). “Those who appropriate public land in excess of the prescribed quotas by one “mau” (equivalent to 3,600 m2) or over shall be punished with 80 lashes, by 10 mau with three-rank degrading, and all the proceeds from such land shall be confiscated into public fund. If they reclaim the waste virgin land, they shall not be penalized.” (Article 343). “Those who purchase land of other people by treading upon their necks shall be degraded by two ranks but allowed to get back their money” (Article 355).

The Vietnamese ancient law in the 15th-18th centuries also clearly provided: “Those who deceitfully claim relatives of someone or collude with others in land appropriation with village chiefs’ connivance shall all be punished by law, and the appropriated land must be returned to eligible subjects as prescribed by law. Those who nonsensically claim land of other people shall be punished with 60 lashes or one-rank degrading.

Major penalties applicable to this group of violations are rank degrading, lashing and exile to a remote location, together with measures to address the consequences or compensations.

Provisions relating to state management of land: Major punitive forms prescribed here were degrading, lashing, hard labor and exile to a remote location. Under these provisions, mandarins who committed acts of encroaching upon public ownership would have to pay compensations two or three times higher than the damages caused (Articles 345, 346 and 347). If provincial, district and commune mandarins let the already allotted land lie derelict, they must compensate for the proceeds there from; if the land was already allotted and yielded fruits, but they reported as deserted land for self-seeking with the proceeds from such land, they must pay compensations doubling the proceeds value into the state budget (Article 347). So, in the division of public land, if mandarins abused their powers for self-seeking, appropriating public property (proceeds), they would be subject to criminal as well as economic penalties. The principle of higher compensations was defined in Article 28 of the Code: “Compensations for material evidences shall double (the material evidences of public property); five times higher than the material evidences of serious offenses; nine times higher (for case of deliberate relapse into crimes)”. The application of this principle to offending mandarins contributed to preventing and deterring them from bullying and harassment of commoners.

Provisions relating to sovereignty protection: Article 74 of the Code provided: “Those who sell national land to foreigners shall be sentenced to death by beheading, the highest penalty.”

Provisions relating to land contracts: The provisions of Articles 383, 384 and 385 of the Code on land contracts contributed to the protection of the ownership of land of eligible subjects, creating legal basis for settlement of disputes.

In short, the above legal provisions of the Le dynasty contributed not only to guaranteeing the legitimate rights and interests of people in the countryside and the local stability but also to strengthening the state control over rural villages and limiting the illegal appropriation by village tyrants of public land as well as private land of local inhabitants. They prove to be helpful for the current judicial reform as well as the current process of building the socialist law-ruled state of the people, by the people and for the people in Vietnam in general and the upcoming revision of its Land Law as well as other relevant laws.-