Dinh Van Tu, L.L.D.

Social Order Administrative Management Faculty

People’s Police Academy

Vietnam’s law on public safety and order-related offenses have constantly evolved through different historical periods, from unclear and lax traditional customs and practices, kings’ decrees and orders and royal codes to strict and specific provisions in modern penal codes. Such crimes were also prescribed in various types of documents, including ancient feudal codes, village conventions, customs and contracts, and in political practices.

Public safety and order-related crimes are defined by law as acts dangerous to the society, committed by people with full criminal liability, that breach the state regulations on public safety and public order and cause damage to the property of the state, organizations or citizens as well as harms to the lives and health of others, affecting routine social activities at public places.

In the pre-1483 period

Before the emergence of “Le Trieu Hinh Luat” (the Criminal Code of the Le Dynasty, also called Hong Duc Code) in 1483, infringements of public safety or order were prescribed mainly by the common or case law being conventions, traditional practices, directives of kings, mandarins, patriarchs, tribal heads, etc. due to the lack of statutory law then[1]. Many traditional practices, village codes and contracts related to public safety and order were established, mostly dealing with the setting up of armed teams to defend villages, prevent quarrels and fighting, and control burglaries and gambling[2]. During that time, acts of breaking public safety were regulated by the common law.

In 968, Dinh Bo Linh took the throne, putting an end to the northern feudalist domination[3]. To secure the public order and maintain the state apparatus, the king paid great attention to the establishment of a legal system, mainly consisting of royal decrees, to severely punish crimes. Notably, in 1125, King Ly Nhan Tong issued a decree stating that “those who beat other persons to death would be penalized with 100 ‘truong’ (strokes of heavy wood stick) and 55 letters carved on the face”[4]. In 1128, he issued decrees on the maintenance of security and order for villagers[5], strictly forbidding the hiding of fighting and murder cases[6]. In 1139, King Ly Anh Tong ordered: “Those who use weapons in land-related disputes, causing death or injury to others shall be punished with 80 strokes of heavy wood stick while the land must be returned to victims”[7]. A decree in 1150 banned the rallying of three or five persons for disparages, specifically stating that sentry soldiers in restricted areas were forbidden to carry weapons, unless with the king’s orders[8].

The Tran dynasty (1225-1400) promulgated “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” (The National Criminal Code) in 1230, defining a number of crimes related to public safety and order, such as rebellion and insulting grandparents or parents. In 1399, King Tran Thieu De issued a decree on maintenance of security and order[9].

The period from 1483 to 1884

“Le Trieu Hinh Luat”

This Code was regarded as a major landmark in Vietnam’s legislative history. Promulgated in 1483, consisting of over 700 articles arranged into six volumes[10], it specified different acts of breaking public safety and order. These acts include causing disturbances at night (Article 69); quarrel, fighting and causing noise in royal courts (Article 91); deadly fighting, murder (Articles 465 and 467); causing disorder at marketplaces (Article 557); causing insanitation at public places (Article 573) etc., with specific penalties. The Code’s provisions were officially and universally applied during the Early Le and subsequent dynasties until the 18th century[11].

|

| On-duty forces protect the scene in My Duc district, Hanoi__Photo: VNA |

“Hoang Viet Luat Le” (the Royal Laws and Regulations or Gia Long Code)

In 1815 “Hoang Viet Luat Le” was enacted with 398 articles and 22 volumes. It contained several sections dealing with acts of breaking public safety and order. For example, Section 236 declared: “Acts of murdering people and rallying up to 10 persons for pestering and wrong doings can be subject to 100 “truong” or exile to 3,000 miles; the gang leaders can be beheaded[12]. Other acts of infringing upon public safety and/or public order include causing troubles to ordinary people (Article 192); attempt to cause disorder (Article 224); public fighting and murder (Article 259); picking quarrels in the royal palace (Article 273); and encroachment upon road beds or pavements (Article 397).

The period from 1884 to 1945

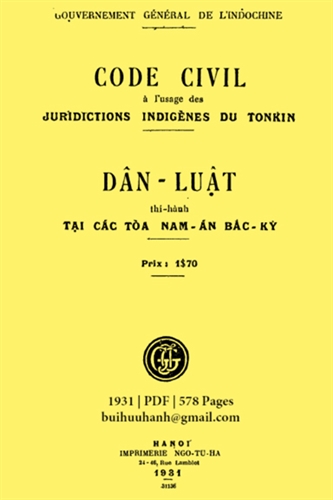

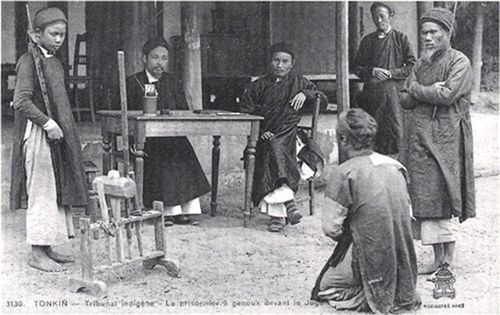

After the French invasion of Vietnam in 1858, especially from 1884 when the royal court admitted the French rule, the country applied both its royal and the French criminal laws to handle public safety and order-related offenses.

In Tonkin, under the semi-protectorate status (excluding Hanoi and Haiphong with the colonial status), courts applied “Bo Hinh luat Bac Ky” (Tonkin Penal Code). In Central Vietnam, under France’s protectorate, excluding Da Nang, “Bo Hinh luat Trung ky” and “Hoang Viet Luat Le” were enforced. Meanwhile, in Cochin-China with the colonial status, the revised Vietnamese Penal Code and the French Penal Code were applied respectively to Vietnamese and French offenders.

The French criminal law applied in Vietnam during this period was the 1810 Penal Code, containing a number of articles on acts of infringing upon public safety and order, such as Articles 330, 434, 438 etc.

The period from 1945 up to now

Earlier in this period, the newly founded Democratic Republic of Vietnam still maintained the previous regime’s regulations while issuing various laws to handle criminal matters. Regulations on public safety and order assurance included Decree No. 35/SL of September 20, 1945, on respect for, and non-encroachment upon, pagodas, temples, churches, tombs and religious venues. Decree No. 31/SL of September 13, 1945, provided that all demonstrations had to be reported to local People’s Committees 24 hours in advance. Besides, Decree No. 26/SL dated January 25, 1946, which was supplemented by Decree No. 92/SL dated June 4, 1946, meted out penalties for acts of deliberately destroying or robbing property of citizens. On October 1, 1952, the Government promulgated eight orders for newly liberated zones, affirming the maintenance of security and order in close association with other issues such as protection of people’s lives and property; protection of temples, pagodas, churches, schools, hospitals and other socio-cultural institutions. Decree No. 267/SL dated June 15, 1956, stated: “Those who rob, waste, destroy or loot property of the State, cooperatives and people for the purpose of sabotage shall be sentenced to between 5 and 20 years in prison (Articles 2 and 6) or “those who destroy public facilities, which are directly related to people’s life, may be sentenced to 20 years in jail or life imprisonment. If causing particularly serious consequences, the convicts can be sentenced to death” (Clause d, Article 8).

In the period from 1954 to 1975, when the country was divided into two regions of North and South, the law on acts of infringing upon public safety and order was applied uniformly in the North. Meanwhile in the South, the Republic of South Vietnam administration maintained the previous codes, which were amended and supplemented by Ngo Dinh Diem administration into the Penal Code with effect from December 20, 1972.

After the complete liberation of South Vietnam and the national reunification in 1975, the Vietnamese State attached importance to building the system of criminal law including those tackling public safety and order offenses. Decree No. 03/SL of the Provisional Revolutionary Government Council on “offenses and penalties” with three chapters and 11 articles was promulgated on March 15, 1976. Since then, different Penal Codes have been enacted and amended in 1985, 1999 and 2015, which all have clearly defined public safety and public order-related offenses.

Particularly, the 1985 Penal Code contained 19 articles on the offenses, including 12 from Article 186 to Article 197 in Section A, Chapter 8 on offenses related to public safety, and seven from Article 198 to Article 204 of Section B of the same Chapter on crimes of infringing upon public order.

The 1999 Penal Code dealt with the crimes of breaking public safety and order in Chapter XIX with 55 articles, from Article 202 to Article 256, 36 more than the previous Penal Code.

The 2015 Penal Code devoted the whole Chapter XXI to prescribing public safety and order-related crimes, with 69 articles, from Article 260 thru Article 329, arranged in 4 sections on traffic safety-related offenses, offenses related to information technology and telecommunications networks; infringements upon public safety and crimes against public order. Typical public safety and order-related crimes include causing public disorder, illegal motorcycle race, obstructing road traffic, breaching regulations on occupational safety and hygiene, on safety at crowded places, violating regulations on construction which cause serious consequences, terrorism, destroying important national security facilities, establishments and/or means, breaching regulations on fire prevention and fighting.

In a nutshell, Vietnam’s law on handling of public safety and order-related offenses has gone through a long history in close association with the course of national development. These offenses have been prescribed more and more strictly and specifically.-

[1] Vu Thi Phung, Ancient Vietnamese codes and a number of their values for modern time, Social Science and Humanity School, Hanoi National University, 2010.[2] Dinh Khac Thuan, Document and content characteristics of traditional village customs and practices, Nghe An culture journal, http://vanhoangean.com.vn.[3] Translation by Vietnam Social Science Institute, 1993, p. 55.[4] Phan Huy Chu, “Lich trieu hien chuong loai tri” (Classified Chronicles of Dynasties), volume III, History Publishing House, Hanoi, 1961.[5] Phan Thi Lan Huong, Phan Thi Duyen Thao: Ideology of giving prominence to the legal theory in Vietnam’s feudal dynasties, Legislative Study Review No. 8, April 2018.[6] Vu Thi Quynh, Vietnamese criminal law in feudal time: Basic features and a number of traditional legal values, master dissertation, Hanoi, 2012.[7] Phan Huy Chu, Ibid, p. 96.[8] Translation by Vietnam Social Science Institute, 1993, p. 141.[9] Vu Thi Quynh, Ibid, pp. 27-28.[10] Phan Huy Le, Vietnamese History Textbook, History of the Vietnamese feudal regime, volume II - The most prosperous development period, Education Publishing House, 1962, p. 159.[11] Phan Huy Le, Ibid.[12] Nguyen Quyet Thang, Summarized study of Hoang Viet Luat Le, Culture and Information Publishing House, 2002, p. 75.