|

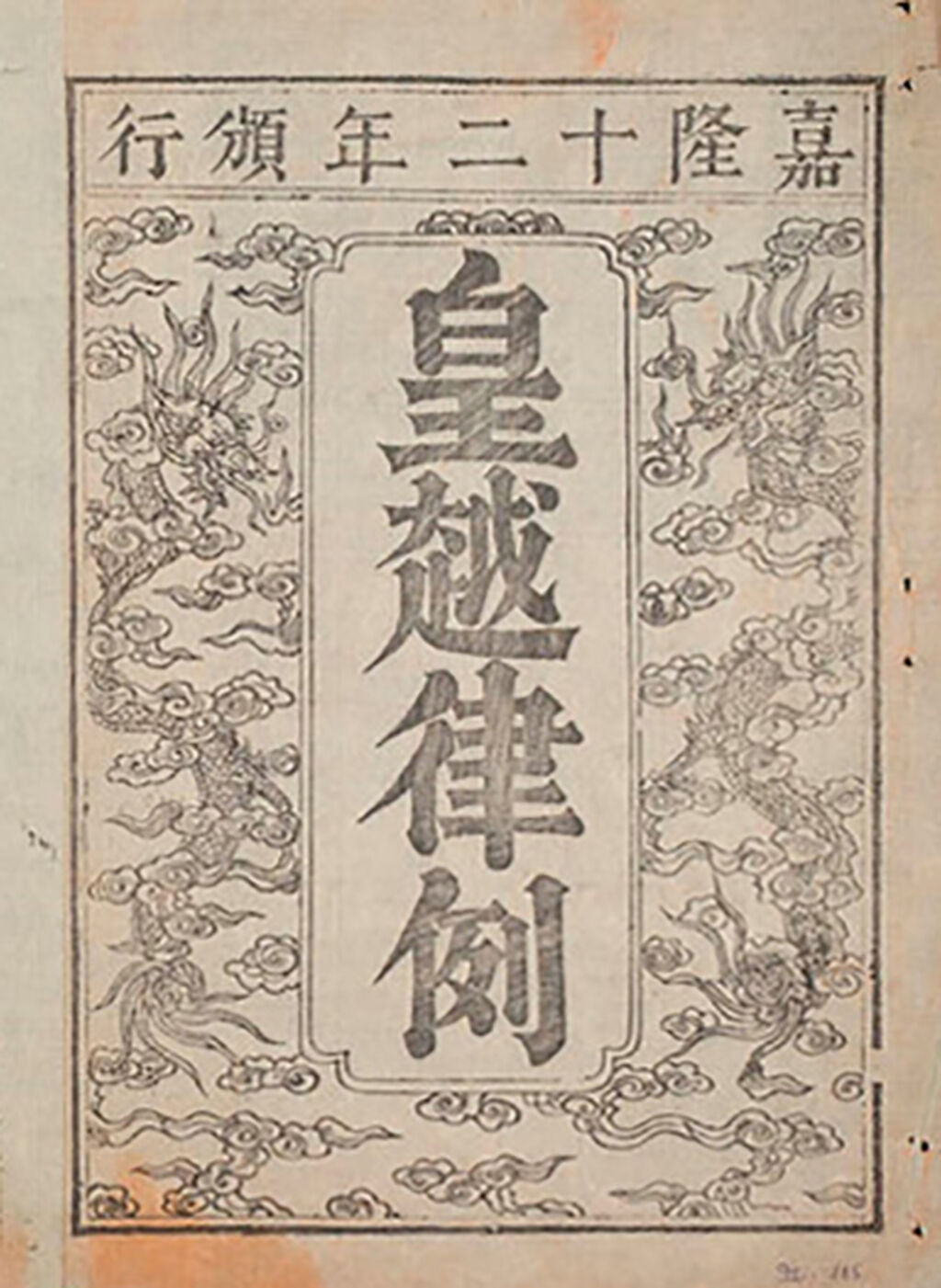

| The cover page of an ancient copy of the Hong Duc Code__Photo: http://luutruquocgia1.org.vn/ |

Ngo Cuong

Statute of limitations constitutes an important institution in civil law, ancient and modern. It bears two meanings. Socially, it aims to stabilize transactions in society within given time limits. Legally, it aims to prevent sine-die litigations which will cause difficulties in determining the evidences of lawsuits.

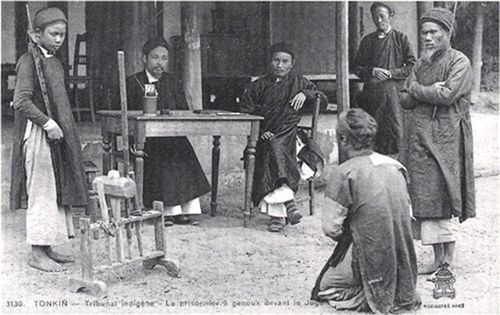

Statute of limitations in feudal laws

Under the Ly dynasty in the second reign year of Thieu Minh (1139), the statute of limitations was clearly established by law: “Those who mortgage their own land can redeem it within 20 years. Land disputes must be reported within five or ten years. Those who leave their land unused and cultivated by others, can sue to reclaim it within no more than one year… The uncultivated land and the sold land cannot be redeemed…”[2]

Under the Le dynasty, the Hong Duc Code provided in Article 387: “Males aged 16 or over, females aged 20 or over, who leave their land to others, including their relatives, for cultivation or residence, can file lawsuits to reclaim it within prescribed time limits (30 years for relatives, 20 years for non-relatives). If they reclaim their land past such time limits, they shall face a penalty with 80 strokes of heavy wood stick and lose their land. This law will not apply to cases where they fled their native places due to wars or led a wandering life and now return”. Regarding debt reclaiming, this Code provided in Article 588: “If past the prescribed time limits (30 years for relatives and 20 years for non-relatives), the creditors fail to reclaim their loans, the loans will be lost”.[3]

The Gia Long Code of the Nguyen dynasty prescribed in Article 89 the time limits to reclaim the sold land but these provisions were unclear. Hence, in the 20th reign year of Minh Mang (1839), these time limits were added: Land sale contracts should clearly state the time limits (for claiming the sold land) to be under five years, five years, 10 years, 15 years or 20 years, but not more than 30 years. If the time limit was not clearly stated, 30 years would be the time limit. In cases where the contracts state the redemption of land can be made within under 30 years, such time limit will be allowed. For those who had sold their land for more than 30 years, they could not reclaim their land even though the contracts mentioned the redemption. Litigation in this case would be rejected.[4]

So, it can be realized that the feudal law in Vietnam prescribing long time limits of up to 30 years for land redemption and debt repayment aims to protect poor farmers from creditors. Meanwhile, the time limit of no more than one year for redemption of land which was left unused and cultivated by others showed the Ly dynasty’s policy of promoting agriculture and preventing the situation of leaving rice fields or gardens uncultivated.

Statute of limitations in civil law under the French domination

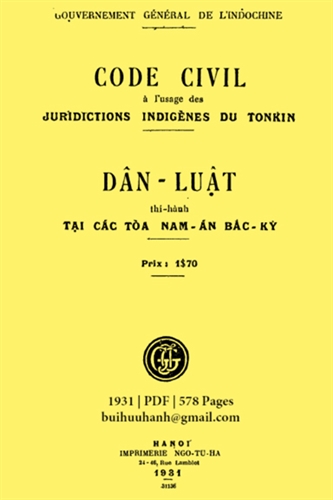

Under the French rule, “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” (Tonkin Civil Code) of 1931 and “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky” (Central Vietnam Civil Code) of 1936 were compiled on the basis of the French Civil Code “ without infringing upon the key regimes of the Vietnamese society but adjusting to suit the customs and level of An Nam people”.[5]

These two codes prescribed the statute of limitations, including “thoi hieu thu dac” (the law-prescribed time limit of property ownership) and “thoi hieu tieu diet” (the time limit for debtors to be free from the debts if the creditors do not reclaim them within the law-prescribed time limit).

Regarding “thoi hieu thu dac”: For the immovables, Article 551 of the “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” and Article 569 of the “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky” provided that those who possess an immovable uprightly, publicly and continuously for 15 years would be the owner of that property. In case of absence of valid contracts as evidence or invalid or false contracts are used as evidences, “thoi hieu thu dac” will be 30 years. For movables, both “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” (Articles 553 thru 555) and “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky” (Articles 570 thru 572) stated: “ Those who possess one tangible object legitimately and uprightly shall be considered the owner of that object; those who have their objects lost or stolen can reclaim them within one year from the date such objects were lost or stolen, the possessors can sue the persons who handed over such objects to them; if the possessors bought such objects at market or public auctions or shops where objects of the same types are sold, the legitimate owners of such objects can reclaim them but have to pay the possessors money amounts equal to the purchase prices.”

Regarding the “thoi hieu tieu diet”, “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” provided “thoi hieu tieu diet” for various obligations to be 20 years (Article 857) and “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky” provided it in Article 935 to be 10 years in cases where the creditors did not demand anything from the time they were so entitled to or where the law did not prescribe a shorter time limit or did not clearly state it was affected by “thoi hieu tieu diet”.

With regard to request for abrogation of invalid contracts, both the Codes set a time limit of five years.

They also provided that judges could not apply at their own will the statute of limitations instead of the involved parties.

Statute of limitations in Vietnamese law from 1945 to before the emergence of the 1995 Civil Code

Following the victorious August 1945 Revolution, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam State promulgated Decree No. 47/SL of October 10, 1945 (which was amended by Decree No. 60/SL of November 16, 1945) and later Decree No. 51/SL of April 17, 1946, permitting the temporary application of the old regimes’ regulations if they did not run counter to the sovereignty and the political regime of the democratic republic. Decree N0. 47/SL clearly stated in Chapter II that in the North (including Hanoi and Hai Phong) and in the “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky” were temporarily retained and the Cochin-china old laws were still applied.

However, in December 1946, Vietnam entered a period of national resistance war. In face of such situation, the Ministry of Justice issued Circular No. 12-NV-CT of December 29, 1946, on judicial organization in special circumstances, clearly stating: “If for any reason, normal courts cannot continue the trials, the adjudication of criminal offenses shall be decided by the Regional Defense Committee and delegated to military courts. Meanwhile, the adjudication of civil or trade cases shall be suspended, except for urgent cases to be adjudicated by specialized jurors of military courts.

For these cases, the time limits nominally prescribed in procedural laws or private contracts as well as the statute of limitations will be suspended from application. Subsequently, the decree will clearly define the conditions for continued application of such time limits”. After northern Vietnam was liberated in 1954, the Ministry of Justice issued Circular 19-VHH of June 30, 1955, and Circular 2140-TT-VHH/HS of December 6, 1955; and the Supreme People’s Court issued Directive 772-NC of July 10, 1959, to suspend the application of previous laws and regulations. Later, no legal documents set forth any statute of limitations. Only after the 1990s, the statute of limitations was prescribed by various ordinances, but they were only for litigation, including the Inheritance Ordinance of 1990 setting the statute of limitations for inheritance litigation to be 10 years (Article 36) and the Ordinance on Civil Contracts of 1991 fixing the statute of limitations for litigation to be three years (Article 56).

So, during the period from 1945 to 1995 before the promulgation of the Civil Code in 1995, in northern Vietnam, the law only prescribed the statute of limitations for litigation. Meanwhile in southern Vietnam, the 1972 Civil Code of the previous regime only prescribed two, namely “thoi hieu thu dac” and “thoi hieu tieu diet” like the “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” and the “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky”.

Statute of limitations in the Civil Codes of 1995, 2005 and 2015

The 1995 Civil Code prescribed the statute of limitations with three types: the statute of limitations for enjoying civil rights; the statute of limitations for release from civil obligations; and the statute of limitations for initiating a legal action.

The 2005 Civil Code retained most of the provisions of the 1995 Civil Code, and only added another type of statute of limitations, namely that for requesting the settlement of civil matters, and made some minor amendments.

The 2015 Civil Code basically retained the provisions on the statute of limitations of the 2005 Civil Code, but added one important provision in Clause 2 of Article 149. It stipulated that courts only apply the provisions on statute of limitations at the request of one party or many parties involved on the condition that such request must be raised before the first-instance courts issue judgments or rulings on settlement of cases. This provision demonstrates the basic principle of civil law that every individual or legal person exercises the civil rights at his/her/its own will, ensuring the objectiveness and impartiality of courts upon the settlement of cases or matters, while preventing the amendment or cancellation of judgments or rulings of first-instance courts when raising the request for application of statute of limitations at the stage of appellate trial or trial review.

As mentioned above, the “Bo Dan Luat Bac Ky” and the “Bo Dan Luat Trung Ky” contained provisions similar to these provisions of the 2015 Civil Code. so did the Civil Codes of a number of other countries such as France and Japan.

Regarding the statute of limitations for enjoying the civil rights (Clause 1, Article 150 of the 2015 Civil Code), the longest duration for this statute of limitations is prescribed in Article 236: “Those who possess or benefit from a property without legal grounds but honestly, continuously and publicly for 10 years for movables and 30 years for immovables, shall be the owner of such property from the time of possession, unless otherwise provided by this law or other related laws”.

For the statute of limitations for release from civil obligations (Clause 2, Article 150 of the 2015 Civil Code), specific provisions on the time limit to enjoy this statute of limitations are not provided in the Civil Code but in other relevant laws. Article 85 of the 2014 Housing Law provides: “2. Residential houses are given warranty upon the completion of construction and pre-use tests within the following duration: a/ For condominiums, at least 60 months; b/ for separate single houses, at least 24 months”. When this time limit expires, the construction parties are no longer obliged for the warranty. Apart from this provision, the Civil Code and other relevant laws only prescribe the statute of limitations for litigation. When this statute of limitations expires, the persons enjoying this right will be no longer entitled thereto and the obliged persons will be released from the obligations towards the former. So, the statute of limitations for release from civil obligations is in fact for initiating the civil cases provided in the Civil Code and other relevant laws.

Article 152 of this Civil Code provides: “Where the law provides that subjects entitled to the civil rights or to be released from the civil obligations under the statute of limitations can enjoy such rights only after such statute of limitations expires. If disputes arise between parties involved over this matter after the statute of limitations expires, the determination of those who are entitled to such rights will be clearly decided by courts.”

It can be realized that the provision of Clause 3, Article 150 of the Civil Code is not reasonable and unconformable with Article 192 of the 2015 Civil Procedure Code. So, in this case, courts must accept the lawsuits. In the course of handling the cases, the courts will determine whether or not they fall into cases defined in Article 156 of the Civil Code. If not, the courts may suspend the settlement of civil cases under Point e, Clause 1, Article 217 of the Civil Procedure Code.

As per Clause 2, Article 149 of the 2015 Civil Code and Clause 2, Article 184 of the Civil Procedure Code, the courts may apply the provisions on statute of limitations only at the request of the parties involved. This means that courts may not apply at their own will the statute of limitations. So, when conducting hearings under Clause 1, Article 210 of the Civil Procedure Code, judges should notify the parties involved that they are entitled to request the application or non-application of the statute of limitations before the court issues a judgment or rulings on the case.-

[1] The Vietnamese version of this article was published on tapchitoaan.vn on may 22, 2023.

[2] Phan Huy Chu, “Lich Trieu Hien Chuong Loai Chi” (Chronicles of Past Dynasties’ Charters, volume 2, the Social Science Publishing House, Hanoi 1992, p. 289.

[3] 2 “Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat” (the Criminal Law of the Royal Court), the Criminal Law of the Le Dynasty, the History Institute, the “Phap ly” Publishing House, Hanoi, 1991.

[4] “Kham dinh Dai Nam hoi dien su le” (The Great Vietnam’s Administrative Records), Thuan Hoa Publishing House, Hue, 1993, volume 11, p.296.

[5] Report of the civil law-drafting council for Vietnamese courts in the Tonkin.