Tran Hong Nhung, LL.D.

Administrative-State Law Faculty Hanoi Law University

|

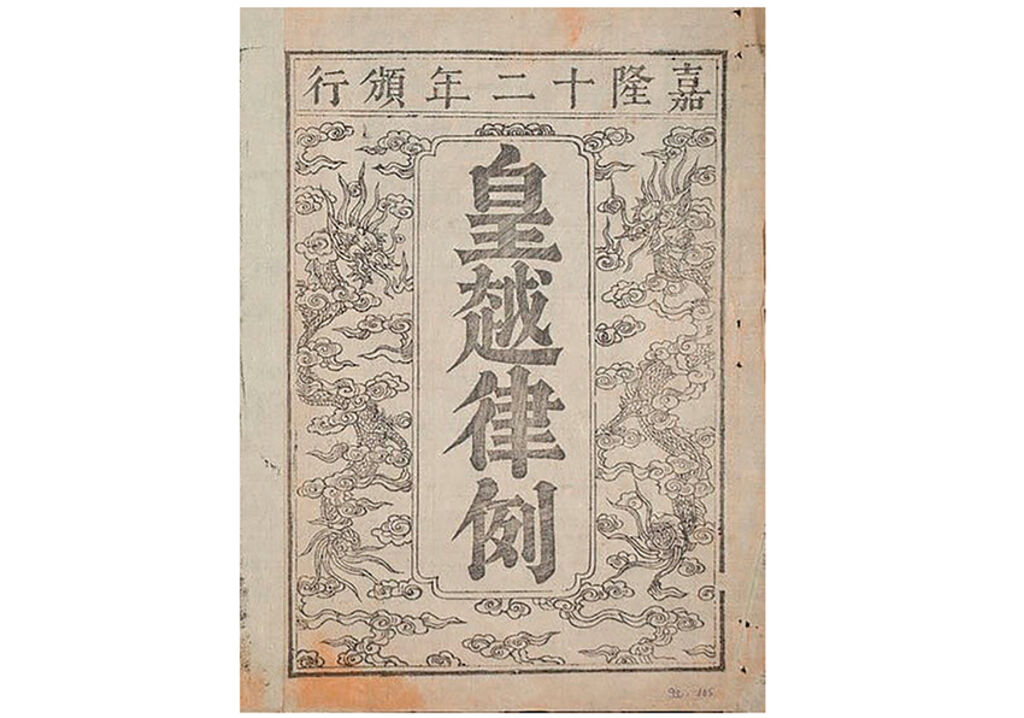

| Hoang Viet Luat Le (The Royal Laws and Regulations of Vietnam)__Photo: https://vi.m.wikipedia.org |

Fully aware of the important role of laws and the need to codify them, Vietnamese monarchies from the 10th to 19th centuries enacted numerous statutory codes and collections of common law for uniform and easy enforcement and application. The feudal states applied two forms of codification, promulgating codes, products of content codification, and collections of common law systems, known today as nominal codification.

Outline of codification achievements under Vietnamese monarchies

Due to subjective and objective factors in each historical period, the legislative achievements varied from kingdom to kingdom. However, the promulgation of different codes stood out as the most fundamental and prominent legislative success of the Vietnamese feudal states. According to historical records, the Vietnamese feudal states compiled and promulgated five codes:

* Bo Hinh Thu (Criminal Code) of the Ly dynasty:

Historian Phan Huy Chu noted that this code, comprising three volumes, was written and promulgated in 1042 during the reign of King Ly Thai Tong. It marked Vietnam’s the first statutory code, representing a great achievement in Dai Viet (Great Vietnam)’s legal history.

* Bo Hinh Thu (Criminal Code) of the Tran dynasty:

Following Tran Canh’s ascension to the throne in 1226, the Tran dynasty promulgated rules and regulations and further supplemented them in 1230 and 1244. On that foundation, in 1341 King Tran Du Tong ordered Nguyen Trung Ngan and Truong Han Sieu to compile Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat (National Criminal Code of the Royal Court), also known as Bo Hinh Thu, in a single volume.

Unfortunately, these two codes were lost for centuries, known only through brief historical accounts.

* Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat (National Criminal Code) of the Later Le dynasty:

This code, considered the oldest code still preserved until today[1], was primarily elaborated under King Le Thanh Tong’s reign at the end of the 15th century and subsequently supplemented by later kings. Composed of 722 articles arranged in 12 chapters and six volumes, it was assessed as the most typical code, the pinnacle of legislative achievements among the various kingdoms.

* Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le (National Procedural Regulations of Royal Dynasties):

This code, elaborated and promulgated in the later years of King Le Trung Hung, is the only one that provided legal procedures. It was the legislative outcome of the whole 18th century, with numerous amendments and supplementations.

* Hoang Viet Luat Le (Royal Laws and Regulations of Vietnam):

This code was compiled in 1811-1812 and promulgated in 1815 under King Gia Long, usually referred in historical records as Gia Long Code. With 398 articles arranged in seven chapters, it was structured largely similar to China’s Dai Thanh Luat Le (Great Qing Laws and Regulations), with a number of different and new provisions.[2]

Along with the promulgation of various codes, the Vietnamese feudal legislators also attached importance to the systemization of single legal documents into diverse and rich collections of common law systems covering various aspects of social life.

The systemization of common law systems was especially promoted during the Ly, Tran, Le and Nguyen dynasties with the promulgation of a series of collections such as Quoc Trieu Thong Che, Quoc Trieu Thuong Le, Hoang Trieu Dai Dien, and Cong Van Cach Thuc during the Ly-Tran dynasties (1009-1400).

Under the Le dynasty, various collections of common law systems and regulations were compiled. They include Luat Thu (with six volumes, compiled by Nguyen Trai); Quoc Trieu Luat Lenh (six volumes by Phan Phu Tien); Quoc Trieu Thu Khe The Thuc (collection of forms of contracts used in common civil transactions during the Le dynasty); Le Trieu Quan Che; Thien Nam Du Ha Tap (with 100 volumes); Hong Duc Thien Chinh Thu; Si Hoan Cham Quy (mandarin-dome rules); Canh Hung Dieu Luat; Quoc Trieu Dieu Luat[3]; Quoc Trieu Hong Duc Bien Gian Chu Cung The Thuc (forms of application and records of cases under Hong Duc’s tenure 470-1497), providing forms of documents to assist law enforcement mandarins and people in writing applications and records of civil and criminal cases, questioning procedures, case examination records, etc. Quoc Trieu Chieu Lenh Thien Chinh is another collection of seven volumes compiled in the 17th century with decrees and orders of Le Kings and Trinh Lords on matters under ministries’ jurisdiction.

During the Nguyen dynasty, there were collections of Kham Dinh Dai Nam Hoi Dien Su Le[4], Dai Nam Dieu Le Toat Yeu[5], Minh Menh Chinh Yeu[6], etc. Of special importance was a great system of documents approved by kings, including all administrative documents on various domains such as politics, diplomacy, economy, culture, social and military affairs, issued from 1802, when King Gia Long was crowned, to 1945, the year when King Bao Dai abdicated.

Generally, during the feudal time, the Vietnamese rulers attached importance to the substantial as well as nominal codifications.

Vietnamese monarchies’ viewpoints on the role of law and the necessity to promulgate codes

In the period from the 11th to mid-19th centuries, Vietnamese monarchies promulgated various codes and thousands of separate legal documents. This demonstrated progress in the feudal states’ views of the role of law in the state administration and management.

In the 10th century, the national legal system did not develop as the country just regained independence after more than 1,000 years of the northern feudalists’ domination. Only during the Ly-Tran dynasties (1009-1400), the feudal regimes embarked on a period of stability and development. This created favorable conditions for promoting legislative work, ushering in the development of Dai Viet’s legal system. The head of the Ly dynasty made an important step forward in legislative thinking, fully aware of the necessity to promulgate statutory laws for people to know and comply with; mandarins to have a foundation for adjudication; and the state has a basis to inspect and oversee mandarins.

In 1428, King Le Thai To ordered mandarins to compile a code for promulgation. He clearly stated: “In the past as well as at present, law is required to rule a country. Without law, a country will fall into chaos. The promulgation of law helps mandarins as well as commoners understand what is good and what is bad so as not to breach the law”[7]. With such view, various kings of the Le dynasty promulgated many legal documents, which were collected, amended and combined into Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat under King Le Thanh Tong’s tenure.

In the 18th century, the feudal lawmakers realized the importance of promulgating a separate code that only regulated the legal procedures in order to “get rid of all bad habits and customs, pacify politics, satisfy the rulers’ aspiration for peaceful rule and the commoners’ desires to enjoy a happy life…”[8]. This is also a distinctive development in legislative thinking of feudal legislators then.

During the Nguyen dynasty as a sovereign kingdom for more than 80 years (1802-84), different emperors from King Gia Long to King Tu Duc attached importance to making laws. Aiming to strictly maintain the state rule, prevent the moral degeneration and establish “golden” royal patterns, in 1811, King Gia Long ordered Nguyen Van Thanh, Vu Trinh and Tran Huu to review royal ordinances and regulations, and consult laws of Hong Duc time and the Qing dynasty of feudal China for compiling laws. In the premise of Hoang Viet Luat Le. He wrote: “… Living in a society, humans have endless desires; without law to prevent them, there will be no way to lead people into moral education. Therefore, our ancestors once said: Law serves as an instrument to help the rule more beautiful”[9].

Principles for law building

According to present-time viewpoints, lawmakers must comply with principles such as legality, respect for objective law, scientificity and timeliness; democracy and publicity; professionalism in legislation; systematicality and feasibility in legal provisions; assurance of harmony between domestic laws and foreign laws, and harmony of interests of social forces, among others. Through studying the process of building and promulgating Vietnamese codes under various monarchies, it is observed that the legislative ideology of then lawmakers almost approached the current viewpoints, as manifest in a number of contents.

The feudal codes in Vietnam demonstrated the harmonious combination between the acceptance of outside political and legal values and the national historical and cultural elements as well as the national requirements of state administration. According to researcher Insun Yu, of 722 articles of Hong Duc Code of the Le dynasty, 261 were borrowed from the Qing dynasty’s criminal code, 53 articles borrowed from the Ming dynasty’s criminal code while 407 others compiled by Vietnamese lawmakers. In addition, the Vietnamese feudal legislators also amended articles borrowed from feudal Chinese laws. For instance, the Hong Duc Code abrogated a feudal Chinese provision that children were not allowed to divide property to lead their independent life when their parents were still alive. Hoang Viet Luat Le of the Nguyen dynasty also revised or abolished many provisions from the Qing dynasty’ law to suit the specific conditions of Vietnam then.[10]

The harmony of Vietnamese feudal laws, including the codes, was also manifest in the compatibility between the law and morality, between protocols and the law, between the law and customs.[11] The ideology of managing the state and the society by law in combination with morality (the rule of virtues and the rule of law), practiced by feudal monarchies in Vietnam also served as an important orientation in the course of social management and law-ruled state building. “This ideology is valuable not only in treasuring the harmonious combination between the law and morality in regulating the social relations, in requiring the ethical values in law but also in laying stress on necessary ‘room’ which the laws should leave for the morality to bring into the fullest play its role in social life”.[12]

Giving prominence to the role and effect of law in social management, Vietnamese monarchs attached importance to law enforcement. King Le Thanh Tong often reminded the courtiers: “As the law is the public law, I and you must comply with. Once the rule of behavior is established, we should maintain and implement…”.[13]

The state must ensure the publicity and transparency of law. “From now on, when decrees and regulations are issued, the ministries in charge, departments, and district administrations must copy and post up for people to know and abide by”.[14] Legal documents were made public by feudal rulers through various forms such as public announcement by village heralds, posting up of notices at public places, and dissemination at population meetings.

In addition, the principles of scientificity, transparency, feasibility, and consistency were demonstrated in the building and promulgation of feudal codes in Vietnam. A researcher remarked: “It can be said that 1,000 years ago, the perception of the Ly dynasty in general and King Ly Thai Tong in particular on codification is not much different from the contemporary idea”.[15] It was for that reason the Hinh Thu (Criminal Code) of the Ly dynasty was preserved by subsequent kingdoms and remained valid until the end of the 18th century.

Codification process

Legislative initiatives were made not only by kings, but also by aristocrats and mandarins. Kings were the only persons empowered to make laws but not directly draft laws.

Laws were compiled through the following principal methods:

(i) The kings assigned agencies or mandarins to elaborate documents in domains under their respective charge and submit them to the kings for consideration, approval and promulgation.

(ii) The kings examined and would approve reports of mandarins and promulgate them into law.

(iii) For documents covering many domains (such as codes), the kings often assigned prestigious senior mandarins in the royal court to compile then submit them to the kings for consideration, approval and promulgation.

Historical records described a strict and serious process of research, compilation, printing and promulgation of Hoang Viet Luat Le. Right in mid-1805, King Gia Long requested courtiers to discuss the compilation of a code of the kingdom. In 1811, he assigned Nguyen Van Thanh (1758-1817), governor-general of Bac Ninh province; Vu Trinh (1769-1828), Minister of Education, Culture and Health, and Tran Huu to gather laws and regulations of previous dynasties, consult feudal Chinese laws, and to select and supplement them to suit the national conditions… In 1812, the code was completed and in 1815 the king issued an order for application nationwide from the start of 1818[16]. The code was effective until 1949 before it was abrogated.[17]

Lawmaking techniques

It can be realized through the structures of the Hong Duc Code and Gia Long Code that hundreds of articles were classified and arranged in a systematic order. Both codes began with a section on general matters and general principles, followed by chapters or volumes composed of articles and clauses on specific domains. Such classification reflects a scientific way of thinking and facilitated reference. These codes comprehensively regulated basic aspects of social relations, including criminal matters, marriage and family, civil affairs, and legal proceedings.

Each article in the feudal codes provided complete legal provisions with three basic components: assumption, provision and remedy. For every specific article, the legislators elaborated the provisions in detail, describing acts, nature, degree and legal consequences. For example, Article 89 of Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat provided: “One month before and after the Emperor is crowned, all families in the royal city are forbidden from organizing funeral services. Those who violate the regulation will be penalized with 50 whippings and demotion by one grade”. Article 585 stated: “In case of a fight between the buffaloes of two families, the dead buffalo shall be divided for meat between two families while the surviving one will be used for field work by both families. Violators will be subject to 80 strokes of heavy sticks.”

Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat and Hoang Viet Luat Le were general codes while Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le only prescribed the legal proceedings with a structure different from two general codes. The latter was composed of 133 articles arranged in 31 chapters. Chapter I contained general provisions on legal proceedings. Chapters II thru XIV provided specific procedures in the legal proceedings. Chapters XV thru XXXI included specific procedures for each group of crimes. With such a rational and clear structure, Quoc Trieu Kham Tung Dieu Le created favorable conditions for application in adjudication.

In summary, alongside legislative experiences, the progressive and humanitarian features, legislative ideas, and the principles, process, techniques and contents of codification found in the ancient Vietnamese codes continue to hold significant values even today.-

[1] Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat, translated by the History Institute, Law Publishing House, Hanoi, 1991.

[2] Nguyen Thi Thu Thuy: On the relationship between Hoang Viet Luat Le and Dai Thanh Luat Le.

[3] Introduction in History Institute’s book - Ancient Law of Vietnam - Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat and Hoang Viet Luat Le, Vietnam Education Publishing House, Hanoi, p.7.

[4] Kham Dinh Dai Nam Hoi Dien Su Le: A book on regimes, regulations and standards of the Nguyen dynasty compiled by the Cabinet of the Nguyen dynasty in mid-19th century, full collection of royal decrees and reports from the first year of Gia Long (1802) to the fourth year of Tu Duc (1851).

[5] Dai Nam Dieu Le Toat Yeu, a collection of legal documents from the reign of King Gia Long to King Thanh Thai. The book comprises four volumes: Volume 1: Lai Le (Regulations on Organization and Personnel); Volume 2: Ho Le (Regulations on Finance, Tax, Citizen Management); Volume 3: Le Le (Regulations on Education, Culture and Health); and Volume 4: Binh, Hinh, Cong Le.

[6] Minh Menh Chinh Yeu: The book on royal life, law promulgation, diplomacy, security, land reclamation during King Minh Menh’s tenure.

[7] Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu (A Complete History of Great Vietnam), vol. 3, Social Sciences Publishing House, 1998, p. 291.

[8] Ngo Cao Lang, Lich Trieu Tap Ky (Chronicles of Royal Dynasties), Social Sciences Publishing House, Hanoi, 1975, p. 260.

[9] Quoc Su Quan Trieu Nguyen (National history of the Nguyen dynasty), Education Publishing House, vol. 1, p. 905.

[10] Nguyen Thi Thu Thuy, ibid.. China Studies magazine.

[11] Hanoi Law University, Textbook on history of Vietnamese states and laws, Justice Publishing House, 2017, p. 59.

[12] Phan Thi Lan Huong, Pham Thi Duyen Thao: Ideology of giving prominence to law in Vietnamese feudal dynasties, Law Study Magazine, Issue No. 8, April 2018, p. 54.

[13] Premise of the Book: Ancient Vietnamese Laws: Quoc Trieu Hinh Luat and Hoang Viet Luat Le, Social Sciences Publishing House, 2009.

[14] Ngo Si Lien and historians of the Le dynasty, Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu, episode 3, ibid, p. 265.

[15] Vu Thi Phung: Ancient Codes in Vietnam and their values for current time.

[16] Quoc Su Quan Trieu Nguyen. Ibid, p. 906.

[17] Nguyen Q. Thang: Brief Reference of Hoang Viet Luat Le, Inquiry into Gia Long Code, Culture and Information Publishing House, Hanoi, pp. 10-11.