Center for Education Promotion and Empowerment of Women, Real-Time Analytics and United Nations Development Program

|

| Director of the Ho Chi Minh City Department of Natural Resources and Environment gives explanations about the land data platform__Photo: https://chuyendoiso.hochiminhcity.gov.vn/ |

Introduction

There was an increase in the number of annual district-level land use plans (DLLUPs) and the 2020-24 provincial-level land pricing frameworks (PLLPFs) available online on local government portals in 2022 compared to 2021. At the same time, local authorities have become more responsive to citizen requests for land information. Despite these positive changes, the difference between the two reviews was not significant, indicating that more should be done by provincial and district authorities to meet the mandate of disclosing information online.

These research findings come from the action research “2022 Review of Local Governments’ Performance in Disclosure of District Land Use Plans and Provincial Land Pricing Frameworks”, which was jointly commissioned by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Vietnam, the Center for Education Promotion and Empowerment of Women (CEPEW) and Real-Time Analytics (RTA) from late 2022 to mid-2023. This study is part of an annual series of action researches on land information disclosure by responsible local government agencies in Vietnam from 2021 to present.[1]

The 2022 review of land information disclosure on official portals of 63 provinces and 705 districts nationwide was carried out from October 2022 to February 2023, as done in the first review in 2021[2]. The initiative focuses on studying the accessibility of PLLPFs and DLLUPs as well as 10-year district-level land use master plans (DLLUMPs), which must be disclosed on the portals of provincial People’s Committees (PPCs) and district People’s Committees (DPCs) by law. At the same time, it examines the local governments’ responses to citizen requests for DLLUPs in all 63 provinces. The level of land information disclosure is evaluated based on five criteria: (i) Information disclosure; (ii) Searchability; (iii) Timeliness of information; (iv) Completeness of information (for district-level land use master plans (DLLUMPs) and annual DLLUPs); and (v) Information usability (easy to read, understand and readable with common software).

|

This article[3] presents key findings from the second-round review of the disclosure of DLLUMPs, DLLUPs and PLLPFs in 2022. It closes with specific recommendations for improved performance in and strengthened policy measures of land transparency at the local level, which contribute to ongoing discussion on amendments to the 2013 Land Law, especially regarding strengthening regulations on land information disclosure and land transparency.

Citizens’ low awareness of local land use plans and land price frames

Local land governance, particularly the hot button issues of land seizures and compensation, has emerged as a high-profile story line and a source of spirited public debate in recent years in step with Vietnam’s dynamic socio-economic development. This discourse has now spilled over into ongoing revisions to the 2013 Land Law, the overarching legal document that regulates land transactions, acquisitions, seizures and compensation. To help inform these policy discussions, the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) in 2022 continued to explore citizens’ perceptions and experiences with local land governance and whether current regulations provide a level playing field.

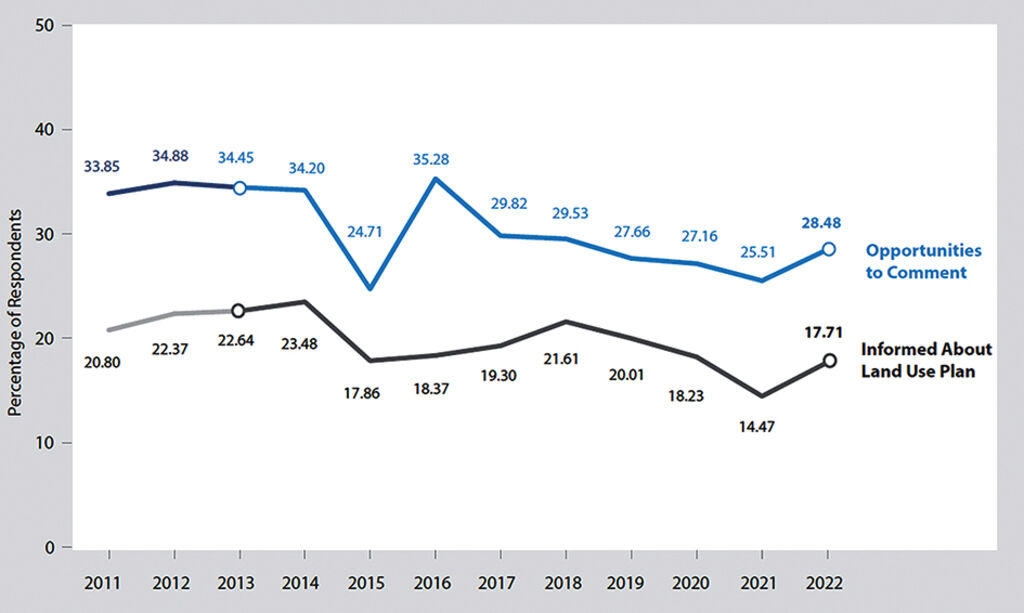

PAPI findings since 2011 have shown that, every year, below 20 percent of respondents are aware of local land use plans, and below 40 percent would know local land pricing frameworks. Particularly, The 2022 PAPI survey results again show how informed citizens were about land plans that may result in land seizures. Notably, as shown in Figure 1,[4] the percentage of respondents who reported being informed about annual district land use plans in 2022 remained low at 17.7 percent, despite a slight 3-percent increase from 2021. Also, the percentage of those who were invited to provide comments on the local land plans was at 28.5 percent, also a rise of 3 percent from 2021. One possibility is that citizens were less likely to demand information about land plans if they were less concerned about the possibility of having land seized. Another possibility is that many local governments did not update and disclose annual local land plans.

|

| Figure 1: Small number of respondents invited to provide comments and informed about the new district land plans |

Furthermore, the 2022 PAPI survey points to citizens’ low awareness of land prices in general, with up to 70 percent of respondents unable to estimate a market or official land price. This knowledge gap is compounded by the finding that many people were only aware of the official land price when personally impacted by a land seizure. Such findings spotlight the need for greater transparency in land values and policies to inform citizens of actual land prices to prepare them if land is acquired.

To understand why there is such a significant policy-practice gap in citizens’ awareness of local land plans and land price frames that fall under the responsibilities of local governments - the supply side, the second-round review of land information disclosure on official portals of 63 provinces and 705 districts nationwide was undertaken. Meanwhile, the 2013 Land Law (the Land Law) and the 2016 Law on Access to Information (the Law on Access to Information) have specified responsibilities, processes, forms, and deadlines for disclosing information on PLLPFs, DLLUMPs and annual DLLUPs as well as the provision of information at the request of citizens.

Slow progress in disclosure of land use plans and land pricing frameworks on local government portals

To obtain more extensive action research findings on citizens’ access to land information in general, in addition to focusing on reviewing the disclosure of information on PLLPFs, DLLUPs and the provision of land information at the request of citizens, the initiative has included the review of the disclosure of the 10-year DLLUMPs by all districts nationwide. Below are key review findings, which are also compared with the 2021 review results where relevant.

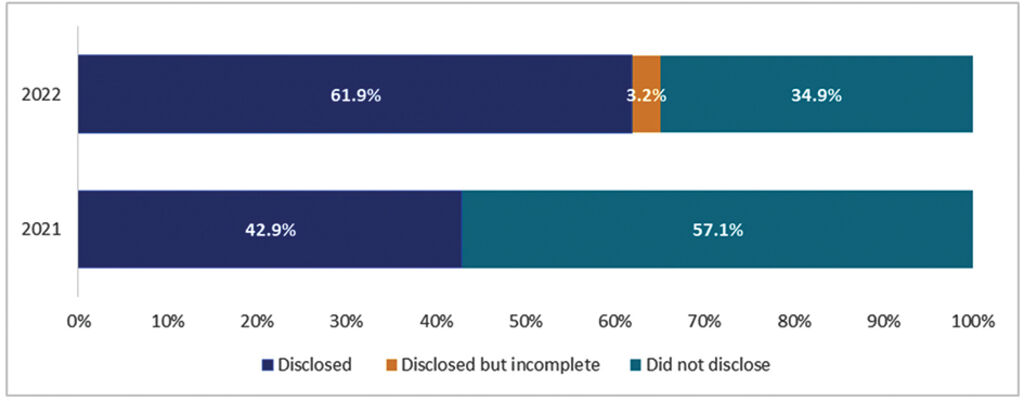

Two-thirds of all 63 PPCs disclosed their PLLPFs of the 2020-24 period on their’ portals

· Information disclosure: The number of PPCs disclosing PLLPFs on their portals in 2022 increased compared to the review findings in 2021. As of October 6, 2022, 41 out of 63 provinces disclosed the PLLPFs on their portals. Compared to the 2021 review results (see Figure 2), 14 more provinces disclosed land pricing frameworks for the 2020-24 period (an increase by 22.2 percent) in 2022. However, under the 2013 Land Law (Article 114.1), all provinces’ 2020-24 PLLPFs should have been disclosed online on January 1, 2020.

|

| Figure 2: Comparison of the findings from the reviews of land pricing frameworks on the provincial portals in 2021 and 2022 |

· Information searchability: Of the 41 PLLPFs that were disclosed online, 22 were found in sections related to land information such as “Land price”, “Land price information” and “Land information”; but seven PLLPFs were disclosed in unrelated sections such as “Document system”.

Fewer than half of all 705 DPCs disclosed their 10-year DLLUMPs of the 2021-30 period on their portals

· Information disclosure: By October 6, 2022, 345 of all 705 DPCs (less than 50 percent) were reported to have disclosed the 2021-30 DLLUMPs. Of the 360 DPCs that were recorded not to have disclosed the DLLUMPs, 52 disclosed a written notice of publicizing the DLLUMPs; one district-level portal was inaccessible during the review process; and 32 DPCs disclosed DLLUMPs after October 6, 2022 - the date when the review team finished reviewing all the portals of PPCs and DPCs within the framework of the second-year review.

· Information searchability: Barely more than half (56.2 percent) of the disclosed DLLUMPs by 345 DPCs had been found in the sections related to land administration; 20 percent found in sections not related to land administration; 15.4 percent found through the search bars in the homepages of the district portals; and 8.4 percent found through Google search.

· Information disclosure timeliness: Out of the 345 DPCs that disclosed the 2021-30 DLLUMPs, 105 DPCs publicized DLLUMPs on time as regulated in the Land Law, while 116 DPCs did not disclose DLLUMPs on time and 124 DPCs did not put the dates when they disclosed their DLLUMPs on their portals.

· Information completeness: 171 out of 345 DPCs fully disclosed three must-be-disclosed documents, including an approval decision, an explanatory report and a map. Meanwhile, four DPCs only publicized approval decisions and explanatory reports, 33 DPCs only disclosed approval decisions and maps, and 11 DPCs only disclosed explanatory reports and maps.

· Information usability: The disclosed DLLUMP-related documents were found mostly in clear and usable scanned soft copies. However, some DPCs compressed their DLLUMP files into a folder and posted them on their portals. In this case, interested users must download the files to their computers and decompress them, which makes it impossible for those who use smartphones to access the files.

A slight increase was seen in the number of DPCs that disclosed their DLLUPs on their portals in 2022 compared to 2021 review findings

· Information disclosure: 389 out of 705 DPCs (55.2 percent) publicized their 2022 DLLUPs. Compared to the 2021 review results, the percentage of DPCs publicizing DLLUPs increased by about 7 percent in 2022.

· Information searchability: Of the 389 DPCs that publicized their DLLUPs, 250 DPCs shared the DLLUPs in sections related to land administration. Meanwhile, 68 DLLUPs were found in unrelated sections, 40 DLLUPs were found by using the search toolbars on DPCs’ portals, and 31 ones were found by Google search.

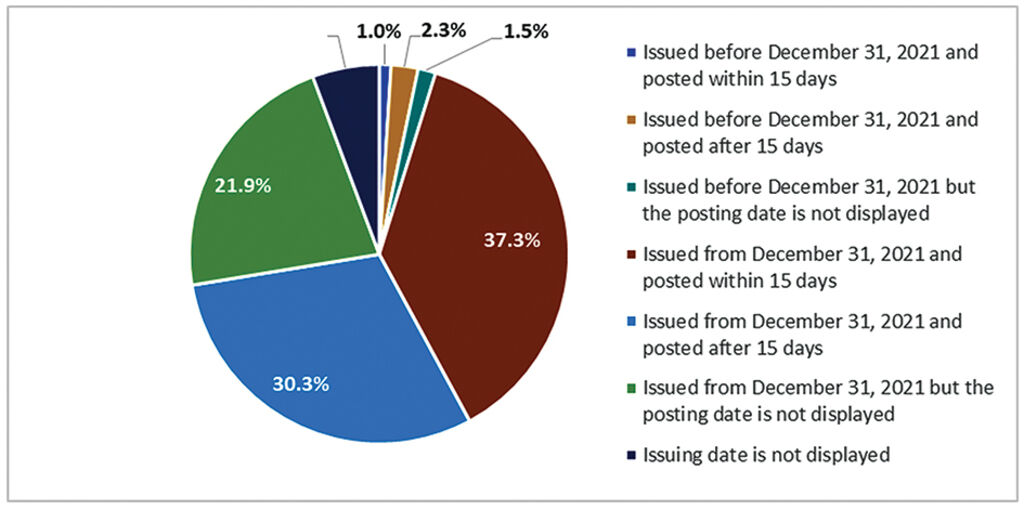

· Issuance and disclosure timeliness: By Decree 148/2020/ND-CP which stipulates that DLLUPs must be issued before December 31 every year, the 2022 review findings show that, of the 389 DLLUPs for 2022 that were issued, only 19 DLLUPs were issued on time, while 348 DLLUPs (89.5 percent) were issued on or after December 31, 2021, and 22 DLLUPs were issued but without specified dates.

Also, as shown in Figure 3, under the regulations on the due date for disclosing DLLUPs online, of 19 DPCs that issued their DLLUPs on time, only four disclosed on time; nine disclosed later than regulated; six disclosed but did not show the dates of disclosure on their portals. Out of 348 DLLUPs that were issued on or after December 31, 2021, 145 DLLUPs (37.3 percent) were disclosed on time; 118 DLLUPs (30.3 percent) were disclosed 15 days after the date of issuance, and 85 DLLUPs (21.9 percent) were uploaded without specified disclosing dates on DPCs’ portals.

|

| Figure 3: Date of approval and disclosure of the 2022 DLLUPs |

· Information completeness: Out of 389 DLLUPs that were made public, 155 (39.8 percent) were fully disclosed with three required documents (i.e., approval decisions, explanatory reports and maps). Meanwhile, 10 publicized DLLUPs included only the approval decisions and explanatory reports, 33 DLLUPs, only approval decisions and maps, and 14 DLLUPs, only explanatory reports and maps.

· Information usability: The 2022 review findings show that most of the disclosed DLLUP documents were clear and usable scanned soft copies. However, many DLLUPs were disclosed as compressed files, which must be downloaded and decompressed to be accessible. In addition, during the review of the disclosed documents, the review team found that the explanatory reports often do not have the seals and signatures of the authorized individuals or agencies. For maps, there were several cases where the maps were disclosed in a format that was not common for the public (DGN), which made it more difficult for users to access the information.

The percentage of district-level state agencies not responding to citizens’ requests for information remained high.

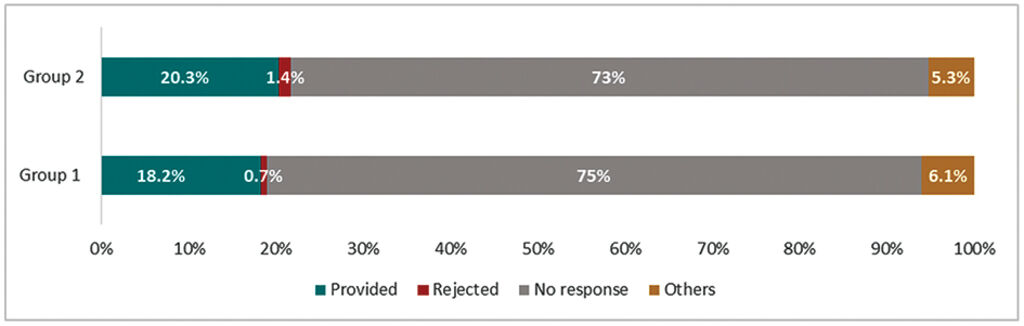

To assess the response rate of providing information to citizens’ requests, the research team representing four types of users (including an ordinary citizen, a real estate trader, a lawyer and a researcher) sent a request for information on the 2022 DLLUPs to 561 DPCs, while the rest 144 among 705 districts are in the control group. On average, each researcher sent 140-141 letters to the DPCs. The letters are divided into two groups. The first group consisted of letters of request for land information citing the Law on Access to Information, and the second group consisted of letters of request for land information citing the Land Law. Form 1a attached to Decree 13/2018/ND-CP was used as the information request form. The experiment’s findings are intriguing and calling for better compliance by district-level state agencies with vertical accountability toward citizens.

By February 21, 2023, 146 DPCs had responded, and among which 108 DPCs provided information as requested, six DPCs refused to provide information, and 32 DPCs provided unexpected responses (e.g., requesting the researcher to direct the request to another state agency and promising to respond via emails later, which never happened). Meanwhile, 415 DPCs (74 percent) did not respond, and this number remained high as found in 2021.

Furthermore, between the two groups of letters of request for information, the letters citing the Law on Access to Information (Group 1) received fewer informative responses (51 responses) than those of Group 2 citing the Land Law (57 responses). Group 1 received two rejection responses and 17 other responses, and Group 2 received four rejection responses and 15 other responses. The response findings of the two groups are shown in Figure 4 below.

|

| Figure 4: Responses to letters of request citing the Law on Information Access (Group 1) and letters of request citing the Land Law (Group 2) |

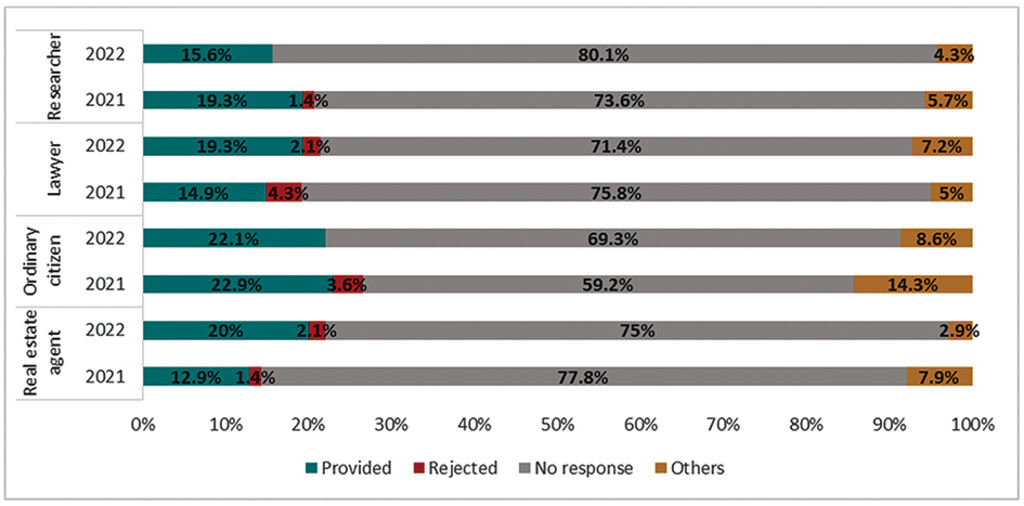

Regarding the level of response in relation to the roles of the requesters, Figure 5 shows the findings of comparing the response level according to each role of the requesters in the two review rounds. Accordingly, the percentage of DPCs providing information to citizens remained almost unchanged; increasing by about 7 percent and 4.4 percent for the real estate trader and the lawyer, respectively; and decreasing by 3.7 percent for the researcher. For all the four requesting roles, the percentage of DPCs not responding to information requests remained high.

|

| Figure 5: Comparison of the 2021 and 2022 findings regarding responses to four types of requesters |

In short, full and timely disclosure of PLLPFs, DLLUMPs and DLLUPs is one of the solutions contributing to reducing current land conflicts. With the growing trend of digital transformation and the high rate of internet users in Vietnam, portals of state agencies are gradually becoming common “places” for people to find information. If designed strategically and synchronously, portals of state agencies, in particular at the district level, will be an effective communication channel between the people and the government.

The survey findings on provincial and district portals for two consecutive years of 2021 and 2022 show that the number of PPCs that disclosed PLLPFs and the number of DPCs that publicized DLLUPs increased over time. In addition, the number of DPCs responding to information requests in the second-year experiment increased compared to that of the first-year review. There are good practices at the provincial and district levels. Box 1 below highlights such good practices for other provincial and district governments to learn from.

As part of the time-series action research, the website https://congkhaithongtindatdai.info has been developed to publicize the findings of the annual reviews and, at the same time, to provide links to PPCs and DPCs’ portals that publicized PLLPFs, DLLUMPs and DLLUPs across Vietnam. It allows users to access and review the level of disclosure as well as the accessibility of land information on the portals of agencies that are obliged to disclose information. Simultaneously, it is expected to be equipped with a function that will allow users to report when the links to the portals of responsible state agencies cannot be accessible.

Recommendations

Addressing information asymmetry about local land plans and land pricing frameworks is one of the key solutions to reduce land-related complaints and conflicts. To promote the disclosure of land information by state agencies, legal provisions and policies related to land information disclosure in and between the Law on Access to Information and the Land Law need to be further improved and synchronized. At the same time, relevant agencies at the provincial and district levels should fully comply with laws and regulations on online disclosure of land information in addition to information disclosure at physical accessible places for citizens to get access to. Below are concrete recommendations for improvement of both policy and practice in land transparency.

|

Development and improvement in legal regulations and policies

· Include the procedures on information provision upon request as provided in the Law on Access to Information in the administrative procedures of all sectors and fields (including land administration) and issue specific guiding texts to avoid the assumption that all requests for land information must comply with the procedures for providing land data currently applied under Circular 34/2014/TT-BTNMT.

· Consider clearly defining the responsibility of the information-holding agency in providing information at the request of citizens in some specific cases. This is also consistent with Article 23.4 of the Law on Access to Information which stipulates that “In addition to the information specified in Clauses 1, 2 and 3 of this Article, based on their tasks, powers, conditions and actual capabilities, state agencies may provide other information that they create or hold”. However, this provision needs to be amended because it gives information holders the right to choose whether or not to provide information even when their information holding is intended to fulfill its responsibility to disclose the information.

· Specify the time limit for making and promulgating land use master plans at each level consistently to ensure that the master plans implemented by the lower-level government is not behind the master plans issued by the higher-level government as well as to ensure the timeliness of information for the people.

· Issue regulations on long-term maintenance of land information on the portals/websites of state agencies in the context of digital transformation. This also helps reduce the burden of administrative procedures on state agencies when the people need to access information, of which the disclosure has expired according to current regulations.

· Retain the time limit for disclosing land information (15 days) as currently stipulated (the Land Law) instead of 30 days as put in the draft revised Land Law.

· Issue requirements on developing interfaces, sections and ways of disclosing information on the Government Portal in a uniform and synchronous manner across the country to make it easier to find information regardless of any portal/website of any state agency.

Effective enforcement of existing laws and policies

· Continue to disseminate and provide training on the Law on Access to Information, Decree 13/2018/ND-CP and Decree 42/2022/ND-CP to all officials and civil servants in state agencies and the people, especially regulations related to the procedures for disclosing and providing information at the request of the people.

· Localities need to develop a section on information access and systematize public information in this section according to Article 19 of the Law on Access to Information so that people can use it anywhere and anytime; formulate and publicize regulations on access to information, arrangement and disclosure of information at the focal point of information provision.

· Design the interface of portals/websites of state agencies in a synchronous manner and improve the functions of these portals/websites. Specifically, the interface needs to be designed in a uniform way among state agencies and it is necessary to ensure that the search toolbar on the homepage or the document system works effectively. In addition, it is suggested to apply Circular 26/2020/TT-BTTTT to support access to information of all users, including people with disabilities and ethnic minorities with limited command of Vietnamese.-

[1] See the Land Transparency Initiative and its findings at https://congkhaithongtindatdai.info/. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Embassy of Ireland, and UNDP jointly funded this study through the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) Research Program of UNDP.

[2] See Vietnam Law and Legal Forum (April 8,2022). Improvement in local governments’ performance in disclosure of land information a must: action research results suggest. Available at https://vietnamlawmagazine.vn/improvement-in-local-governments-performance-in-disclosure-of-land-information-a-must-action-research-results-suggest-48853.html.

[3] This article is composed by Do Thanh Huyen, Policy and Program Analyst, UNDP in Vietnam based on the working paper “The second review of the disclosure of district-level land use master plans, plans and provincial-level land pricing frameworks in 2022”, which was commissioned and finalized by the CEPEW, Real-Time Analytics (RTA) and UNDP in Vietnam in May 2023

[4] See CECPDES, VFF-CRT, RTA and UNDP (2023). The Viet Nam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) 2022 Report, page 30. Available at https://papi.org.vn/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2022_PAPI_REPORT_ENG_E-book.pdf