Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development and United Nations Development Program in Vietnam[1]

|

| A member of the Thanh Hoa province’s Ho Chi Minh Youth Union (in blue shirt) answers inquiries about the exploitation of the National Residence Database__Photo: Nguyen Nam/VNA |

Introduction

This article presents key findings from the first-ever review of user-friendliness and accessibility of 63 provincial e-service portals (PESPs) conducted by the Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development (IPS) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Vietnam from October 2022 to August 2023. The review was done by two groups of users: regular users and users who are ethnic minority people and people with disabilities. The e-service for application for criminal record certificates was selected as the case study to investigate processes behind the PESPs. Moreover, to verify the key findings against real-life experiences of the direct users of the e-services, 200 user feedback and recommendations for improving e-services were posted on the National E-Service Portal (NESP) from November 28, 2022, to April 11, 2023. Finally, this article proposes solutions to make public e-services more user-friendly and accessible for all people, including ethnic minorities and people with disabilities.

Large policy and practice gaps in development of citizen-centric e-services

Digitalization of public services is an important priority of the Vietnamese Government to enhance administrative reform in the 2021-30 period. This has been reflected in Vietnam’s National Digital Transformation Program by 2025, with a vision toward 2030[2], and the Strategy for the Development of E-Government toward Digital Government for the 2021-25 period, with orientations toward 2030[3]. This is simultaneously the objective of building and developing e-government, digital government in the country’s Public Administration Reform Master Plan for the 2021-30 period.[4] These programs and strategies all embrace the perspective of adopting a user-centric approach and using citizens’ satisfaction as the evaluation measure. Some of the ambitious goals set by the Government (by 2025) are to provide all eligible administrative procedures as end-to-end e-services, accessible through various channels, including mobile devices; to design and redesign all electronic government services (EGSs) to optimize user experience, seamless identification and authentication with pre-filled data; to ensure all citizens and businesses use seamless identified and authenticated EGSs that are integrated across all levels of government systems, from central to local; and to ensure at least 90 percent of citizens and businesses are satisfied with the settlement of administrative procedures.

Since 2021, the legal framework for promoting the implementation of electronic public administrative services (e-services) has been increasingly improved. Specifically, it covers five key aspects: (i) implementation of the single-window and inter-agency single-window mechanisms in the settlement of administrative procedures; (ii) electronic identification and authentication; (iii) management, operation and exploitation of e-service portals (ESPs); (iv) evaluation of the quality of services for citizens and businesses in administrative procedures and public services; and (v) removal of bottlenecks for the development of e-government.[5] The current priority task is to promote the implementation of eligible administrative procedures entirely online and integrate them into the NESP.

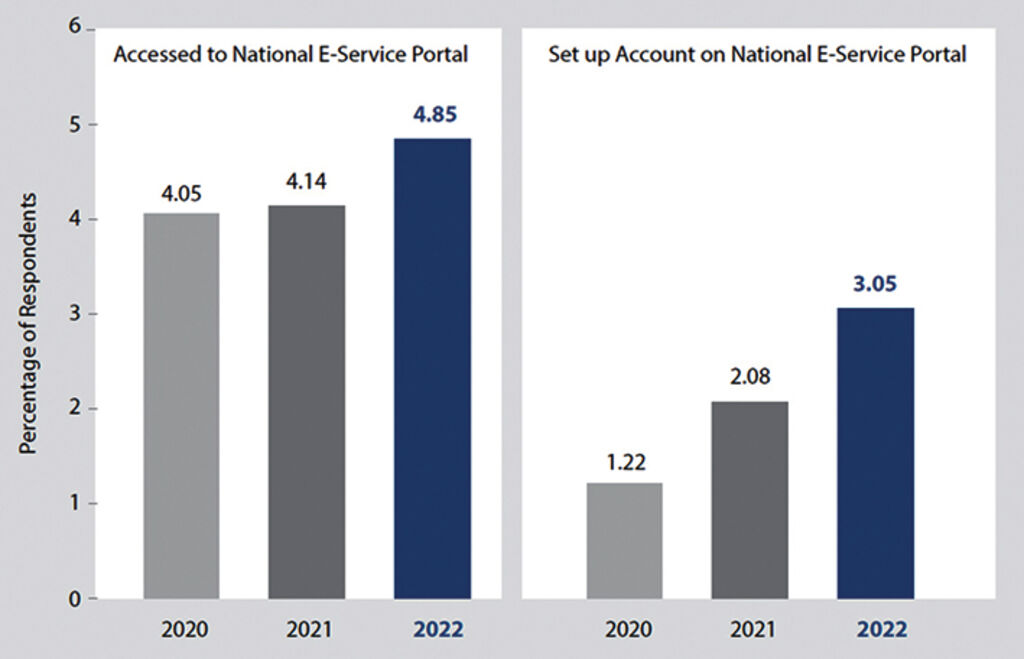

However, statistics show that the usage rate of e-services by citizens has been constantly low. According to the report of the National Digital Transformation Committee,[6] the percentage of citizens using online public services accounted for 1.78 percent in 2020, 9.51 percent in 2021, reaching only 18 percent in the first seven months of 2021. Additionally, survey data from the Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) for 2022[7] revealed, as shown in Figure 1, that only 3.05 percent of respondents reported having created user profiles on the NESP (the right bar graph), and 4.85 percent had used the NESP for various purposes (the left bar graph), among whom barely over 1 percent used the NESP for submitting administrative procedures online.

|

| Figure 1: Percentage of citizens that used the National E-Service Portal, 2020-22 |

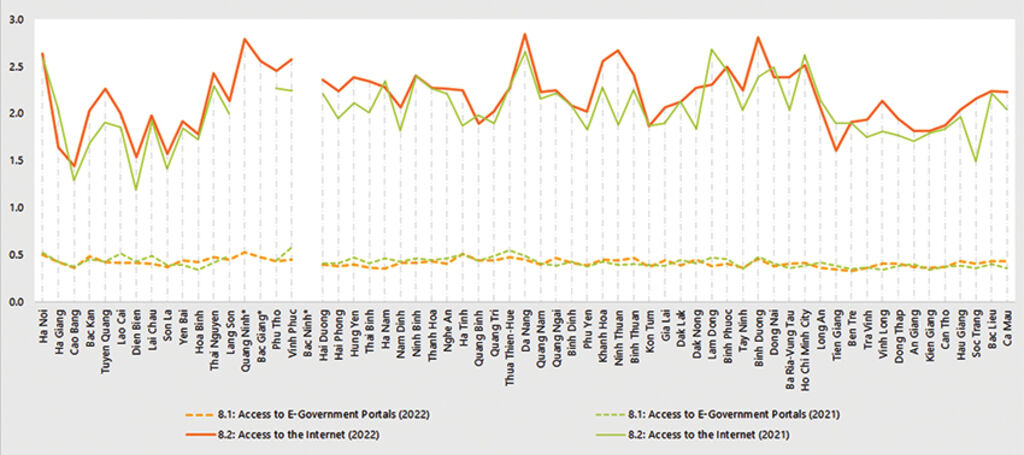

Similarly, the proportion of users of PESPs was also very low, at nearly 4.3 percent nationwide in 2022, while up to 71 percent of the 2022 PAPI respondents said they had the internet access at home. Figure 2 below illustrates the gap between citizen access to internet at home and citizen use of online government services in 2021 and 2022 from the two years of PAPI surveys. If the e-service usage rates remain so low, it will be difficult for Vietnam to achieve its national digital transformation targets by 2025.

|

| Figure 2: Divide between access to the internet and access to e-government portals for e-services in 2021 and 2022 |

* Missing data in Bac Giang, Bac Ninh and Quang Ninh

Moreover, findings from the action in-depth research series by the Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics and UNDP in Vietnam on the access to online public services for ethic communities in six provinces of Ha Giang, Hoa Binh, Quang Tri, Gia Lai, Soc Trang and Tra Vinh from 2021 to 2023[8] also revealed that the use of e-services in all six provinces was extremely limited. The main barriers include lengthy and burdensome requirements for logging into the ESPs and administrative procedures from government agencies as well as the lack of readiness by citizens to use the e-services. For instance, the request for registration and log-in with usernames and passwords before the use of an e-form for a simple administrative procedure could have prevented users from using e-services. This is let alone important technical issues like poor internet connections, flawed system configuration and lack of data synchronization that local governments have been facing.

Therefore, it is essential to conduct a review of user-friendliness and accessibility of 63 PESPs to understand current obstacles to users and propose solutions to increase citizens’ usage. The sections below present key findings from the review of user-friendliness and accessibility of all 63 PESPs by three groups of criteria: (i) information retrieval and search functionality in terms of availability, effectiveness, and ease of use; (ii) online administrative procedure performance in terms of intelligence and convenience for users; and (iii) user-friendliness of PESPs’ interfaces.

PESPs not yet user-friendly for all and accessible for disadvantaged citizens

The review findings show that there are challenges in implementing end-to-end EGSs, and that the interfaces of PESPs do not fully adopt a user-centric approach. Below are key obstacles for an ordinary citizen to use a PESP.

The search tools on most PESPs are not yet user-friendly. Specifically, 36 portals do not display the search tools on their homepages, requiring users to spend exhaustive time searching through sub-pages. The search tool is not effective either, as 25 portals do not generate results if the keywords are misspelled. Even, four PESPs of Cao Bang, Tuyen Quang, Lai Chau and Yen Bai provincial governments require users to log in before conducting a search, and four PESPs of Son La, Quang Ninh, Bac Giang and Phu Yen provincial governments require users to include the state agency’s name before searching.

There has been a lack of attention to the quality of user manuals. Although user manuals are available on 62 out of 63 PESPs (except the one in Yen Bai province), such manuals are presented clearly and directly, but the quality and usefulness of these documents have not received adequate attention. There is a lack of synchronization in the naming and search location of the user guide documentation sections across all PESPs. Also, the user manuals are not simple to use: 17 PESPs directly use user manuals provided by technical service providers (specifically the VNPT) instead of adjusting and updating, while only 24 ESPs provide user guide documentation in text, image, and video formats.

The features for implementing end-to-end ESPs are not yet adequate. The test results for processing the “Issuance of Criminal Record Certificate”[9] service reveal that many PESPs do not allow users to complete this service fully online. There are 26 ESPs that require users to submit original documents for verification if they submit scanned or online copies. Moreover, 24 ESPs do not allow for online delivery of the Certificate but require users to choose to receive the result by mail or in person at the receiving agency instead. It is noteworthy that 17 ESPs require users to make online payments before submitting their documents. This situation creates the drawback that if the documents are invalid, the receiving agency must take an extra step of refunding the fee to the user. These existing issues indicate the risk of misunderstanding that end-to-end ESPs have been provided when they are only partially online.

None of PESPs provides complete specific instructions for users to independently complete their application. Some PESPs (e.g., those of An Giang, Ninh Binh and Quang Ngai provincial governments) require users to enter personal information (such as information of the applicant, information of the document submitter, additional information, and electronic declaration information) for multiple times. It is noteworthy that the declaration form for issuing a criminal record certificate has only been converted from its original paper form into electronic form, without flexible technical improvements to facilitate user convenience in the digital environment. As for the function of submitting online application, the PESP for “Issuance of Criminal Record Certificate” has not been user-friendly for applicants. The classification of application cases is currently designed based on the direct needs of the document processors, which creates difficulties for applicants as they must understand the procedures and the corresponding classification themselves.

There remain challenges in connecting data, user accounts, and interfaces between the central and local ESP systems. As of May 30, 2023, only Thai Nguyen’s PESP displayed a feature that allows updating personal profiles from the national population database. Meanwhile, the PESPs of Hai Phong, Ninh Binh, Thua Thien-Hue, Da Nang and Bac Lieu provincial governments have not yet allowed automatic login from the NESP or the Vietnam Electronic Identification (VneID) accounts. For the service experience of “Issuing criminal record certificates for Vietnamese citizens and foreigners residing in Vietnam,” the PESPs of Soc Trang and Ca Mau provincial governments even confuse users because, while they post a note requesting applicants to “Submit applications through the National Public Service Portal,” the NESP redirects users to the Provincial Departments of Justice’s ESPs when users access through the NESP.

The commitment to protecting personal data and ensuring information security has not been given due attention. Among the 63 PESPs, only three PESPs of Thua Thien-Hue, Da Nang and Gia Lai provincial governments[10] have posted privacy policies, as the review results in 2022 revealed.[11] In terms of meeting information security standards from the perspective of popular web browsers[12], only 10 PESPs meet at least seven out of 11 basic safety criteria.

PESPs are not yet accessible for persons with visual impairment and people with Vietnamese language barriers. All 63 PESPs are difficult to access for users with visual impairment and ethnic minority communities. For visually impaired users, the support of screen reader browsers is necessary. However, none of the portals ensure all six criteria for basic accessibility as specified in the global guidelines known as Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 for accessible websites. For ethic minority communities, 62 portals do not supply voice search functionality, while the search tools of 25 portals do not yield results if the search keywords are misspelled, causing difficulties for ethnic minority users who may not be proficient in writing standard Vietnamese.

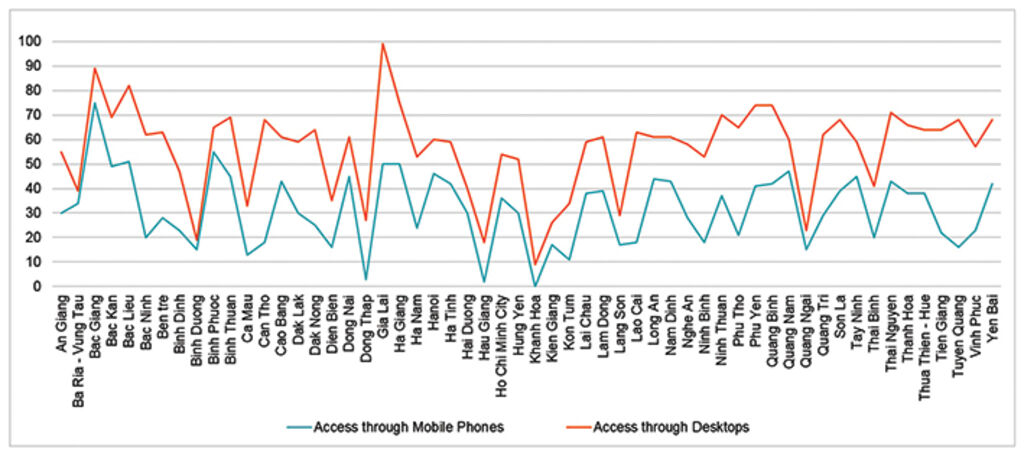

PESPs are not yet user-friendly on mobile phones. Results from the review of 56 PESPs that allow accesses from both desktop and mobile phones indicate that the page loading performance of desktop-based interfaces is consistently better than that of mobile phone-based interfaces (see Figure 3 for detail). Specifically, the average page loading performance on the mobile interface is 31.4 points on a 0-100 point scale, corresponding to poor loading speed and resulting in a suboptimal user experience. On the other hand, the average page loading performance on the desktop interface is 56.1 points, corresponding to fair loading speed.

|

| Figure 3: Comparison of loading speeds of 56 provincial e-service portals when accessing through mobile phones and desktops (on a 0-100 point scale) |

User feedback reveals limitations in technology, human resources and processes. The in-depth analysis of 200 user feedback and recommendations on the NESP confirms the findings from the evaluation of the 63 PESPs. User feedback also shows that the implementation of PESPs is facing many limitations in all three aspects: technology, human resources and processes. Technical issues include faulty ESPs, lack of online submission guidelines, no online application submission option, inability to update profiles online, inability to make online payments, inability to submit additional documents online, outdated data, system failure to update application status promptly, and rejected digital signatures. Human-related shortcomings include officials returning applications with insufficient reasons, failing to explain or guide citizens when applications are incorrect, not answering hotline calls promptly to address citizen queries, lacking clarity about the processes, showing inappropriate attitudes, and creating unnecessary difficulties for citizens to ask for bribes. Process-related and procedural limitations include delays in the application acceptance process, requests for online applicants to provide additional documents in person, and unclear processes for online submission, acceptance, return, and rejection of applications.

Recommendations for improved ESP performance and ESP development policy

From the review findings above and the extensive review report by IPS and UNDP (2023), we make several recommendations to improve the performance of PESPs and to develop ESPs in Vietnam as listed below.

Recommendations for enhancing user-friendly and easy-to-use interfaces of PESPs

Usability of search and information retrieval tools: It is required to ensure the synchronization of advanced search tools in three aspects: (i) easily accessible and displayed on the homepage; (ii) optimized for keyword search and providing suggestions for closest search results; and (iii) incorporating voice search functionality.

Availability and usability of user support tools: It is a need to standardize the interface and content requirements for three user support tools: (1) user manuals; (2) frequently asked questions (FAQs); and (3) interactive features with virtual assistants. For user manuals, important principles to consider include: (i) prioritizing the use of visual images and short, intuitive videos; (ii) using user-friendly language, avoiding abbreviations, foreign languages, and technical terms; and (iii) clearly classifying user manuals based on the EGS process and the target audience (officials or citizens/businesses).

Availability of contact information: It is suggested to ensure that each locality provides all three types of contact information, including: hotlines for administrative procedure support, technical support hotlines, and contact information for the one-stop-shop department in all relevant offices. The display location of contact information should be easily accessible for users.

Transparency in providing information on the effectiveness of EGS delivery: In addition to overall statistics on the number of timely and delayed applications, the following additional information should be publicly disclosed: (i) number of days delayed; (ii) names of departments or agencies with pending applications; (iii) reasons for delays; (iv) content of the applications; and (v) content of additional documents required. These indicators allow citizens and management authorities at all levels to monitor and supervise the process while putting pressure on officials/agencies to complete their work on time.

Intelligence level of ESPs: First, it is proposed to enhance data connectivity between the NESP and PESPs. Second, the electronic document component needs to be redesigned. Electronic forms should provide direct guidance at each data entry field and allow users to save/update the form. Error reporting features should also be improved to enable users to identify and correct errors promptly. Third, it is necessary to review and improve features facilitating online application submission, payment, and receipt of application results.

Creating conditions for citizens to evaluate their satisfaction level: It is a must to standardize tools for citizens to evaluate their satisfaction level, divided into periodical evaluations and regular evaluations. For regular evaluations, in real-time, the goal is to measure citizen satisfaction. The evaluation form should meet both of the following criteria: (i) accessibility - ideally, it should be available immediately after completing the application process; and (ii) simplicity (maximum five questions) that can be quickly completed (within 45 seconds), preferably using a star rating evaluation method. For periodical evaluations, the goal is to assess users’ in-depth experiences to identify areas that need improvement. Therefore, the questions can be more detailed, including both quantitative and qualitative questions, and should focus on specific services or service groups that require improvement.

E-service interface’s user-friendliness level on mobile phones: The management units of the ESPs need to use tools to evaluate the user-friendliness level of the interface on mobile phones and make appropriate adjustments. Additionally, it is necessary to enhance the capacity of the technical teams of the Departments of Information and Communications in reviewing the usability of ESPs on smartphones.

Accessibility level for people with disabilities: The management units of the ESPs need to regularly (monthly or quarterly) use automatic scanning tools (WAVE Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools[13] and Accessibility Insights[14]) to review, detect, and improve the accessibility for people with disabilities using screen readers, as well as other user groups with similar needs. Depending on the resources of each province or city, it may be possible to invite groups of people with disabilities to participate in evaluating the user experience of the ESPs, thereby making appropriate adjustments.

Commitment to safeguarding personal data and information security: It is required to ensure measures to protect personal data and information security on the interfaces of the ESPs. The ESPs need to ensure standard terms of use, privacy policies, and mechanisms for user consent. Regarding information security, regular reviews and assessments should be conducted to avoid basic technical errors that may lead to personal information breach.

Recommendations for improving policies to promote development of EGSs

Firstly, it is necessary to focus on quality rather than quantity by prioritizing the improvement of the online provision process for 25 essential e-services. In the case of introducing new policies (such as transitioning from classifying e-services into levels 1, 2, 3 and 4 to end-to-end-online/partial-online classifications), pilot deployments should be conducted in representative provinces and cities (e.g., Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, which are densely populated and have the highest number of migrants in the country; and Ha Giang and Quang Binh, which have many communities in remote and underdeveloped areas with difficult information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure) before nationwide implementation. During the testing or trial operation of ESPs, there should be policies to ensure user participation for receiving feedback from the public.

Secondly, it is a need to ensure accessibility for vulnerable groups to achieve “leave no one behind” digital transformation. Some measures include: (i) mandating criteria for accessibility (WCAG and similar international standards) for ICT products and services in public procurement activities, where accessibility standards are mandatory contract terms; (ii) initiating policies for developing accessibility assessment services to create right conditions and encourage the participation of disabled and elderly users in assessment activities; and (iii) promulgating a policy that facilitates public-private partnership between local governments and domestic and international technology companies to develop language support tools such as video clips in ethnic languages and screen readers for automatic reading interface screens for ethnic minority languages and individuals with visual impairment.

Last but not least, it is vital to establish regulations on technical standards for connecting and interoperating the e-service delivery systems. In the context of continuous updates and changes in e-government and digital government in the next five to 10 years, this standardization will provide a solid foundation for adaptation to the changes, reducing the costs of transition and updates. Moreover, regulating the connection standards of e-government and digital government systems at various levels aims to create opportunities for technology startups and small- and medium-sized service providers to contribute to the e-government and digital government ecosystem, thereby promoting the development of Vietnam’s technology market.-

[1] This article is an extract from the joint policy research report “First Review of Accessibility and User Friendliness of 63 provincial e-service portals in 2023” commissioned by the Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development (IPS) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Vietnam and released in October 2023. It is composed by Do Thanh Huyen, Policy and Program Analyst, UNDP in Vietnam.

[2] See https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Cong-nghe-thong-tin/Quyet-dinh-749-QD-TTg-2020-phe-duyet-Chuong-trinh-Chuyen-doi-so-quoc-gia-444136.aspx for more information.

[3] See https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Cong-nghe-thong-tin/Quyet-dinh-942-QD-TTg-2021-Chien-luoc-phat-trien-Chinh-phu-dien-tu-huong-toi-Chinh-phu-so-477851.aspx for more information.

[4] See https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bo-may-hanh-chinh/Nghi-quyet-76-NQ-CP-2021-Chuong-trinh-tong-the-cai-cach-hanh-chinh-nha-nuoc-2021-2030-481235.aspx for more information.

[5] See the list of referenced legal documents in IPS and UNDP (2023).

[6] See https://vtv.vn/xa-hoi/vi-sao-nguoi-dan-chua-man-ma-su-dung-dich-vu-cong-truc-tuyen-20220821062744991.htm for more information.

[7] See the Vietnam Provincial Governance Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) reports for 2021 and 2022 at https://papi.org.vn/eng/bao-cao/.

[8] See the series of the action research working papers in these provinces at https://papi.org.vn/eng/thematic-research-reports/?title=quan-tri-dien-tu.

[9] The public service of issuing Criminal Record Certificates is available to two groups of individuals: Vietnamese citizens and foreign residents in Vietnam.

[10] The PESP of Gia Lai province has only the English version.

[11] For detailed assessment of the protection of personal data, see IPS and UNDP (2022). Review of Local Governments’ Implementation of Personal Data Protection on Online Government-Citizen Interaction Interfaces, 2022, Hanoi, 2022, available at https://papi.org.vn/eng/danh-gia-viec-bao-ve-du-lieu-ca-nhan-tren-cac-nen-tang-tuong-tac-voi-nguoi-dan-cua-chinh-quyen-dia-phuong-nam-2022/.

[12] Assessed by using the tools available at https://observatory.mozilla.org/.

[13] See https://wave.webaim.org/ for more information.

[14] See https://accessibilityinsights.io/ for more information.