Ta Thi Tam

Ethnology Institute

|

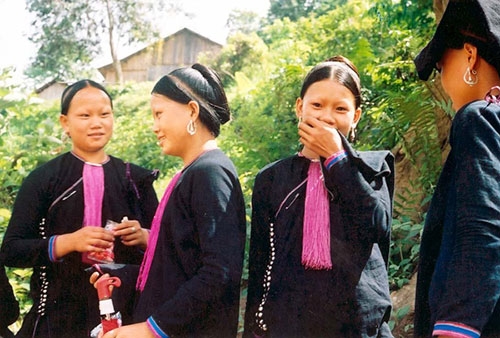

| Ky Yen ritual of the Ngai in Bac Giang province, for good weather, bumper crops and peaceful life__Photo: Internet |

The Ngai is a small Sino-Tibetan language group living mostly in the northern province of Thai Nguyen with a population of over 1,000.

Due to their small population, the Ngai do not live in separate villages but together with other ethnic minority groups.

A Ngai traditional house has earth walls and a thatched roof. A home consists of two parts: the main house located on the right side and the kitchen, well, toilet and animal breeding facilities set up separately on the left.

In the main house, the ancestor altar is set in the middle part facing the entrance door. In this part, a table and chairs are placed for receiving guests. The left and right parts are for sleeping, with women sleeping in separate rooms.

The Ngai have certain beliefs and taboos when choosing the site to build their home. The position and direction of their future home are selected based on the ages of both the husband and wife. The dates for breaking the ground and celebrating the new home must also be chosen carefully. When cerebrating the new home, the family invites a shaman to officiate a ritual to carry the incensory onto the altar and invite ancestors to the new home.

Food of the Ngai includes ordinary rice, sticky rice, maize and soy bean. In the past, the group used to eat porridge due to food shortage. Ngai specialties include khau nhuc (well-stewed pork mixed with a dozen of spices and herbs), pickled dry beet and salted pork. The Ngai make their own sauce from soy bean as a seasoning for meat, fish and tofu dishes. They also make different cakes from ordinary and sticky rice, such as three-angle cake (made of sticky rice and black bean), banh bo (sweet dumpling), banh day (round sticky rice cake), banh chung (square sticky rice cake with pork and green bean fillings), banh tro (cake made from sticky rice soaked in a liquid of burned herbs before being boiled), and banh rom (steamed round sticky rice with pork and Jew’s ear fillings). These cakes are indispensable dishes in Ngai festive events such as new year festival, wedding, birthday, new home celebration, etc.

Costumes of the Ngai vary depending on the sex, age and social class of wearers. Well-off people wear white or chicken fat colored clothes while poorer ones use indigo-dyed wear. A Ngai man wears an open-collar and cloth-buttoned shirt with two or three pockets and quan chan que la toa (trousers with wide and straight legs, long crotch and broad upper hems). A Ngai woman wears a long five-flap shirt without pocket, buttoned at the right underarm seam, and ankle length straight pants with a cloth belt.

Marriage rules of the Ngai are strict. The group used to follow endogamy but marriage between members of the same clan was prohibited. Today, marrige with people from other ethnic groups is allowed.

A Ngai marrige completely relies on a matchmaker. When a man wants to get married, he must find a matchmaker to visit the bride’s family, asking for their consent. After being accepted by the bride’s family, the matchmaker brings the groom’s horoscope to the bride’s to see if the couple is a good match. If yes, wedding formalities will be carried out with four ceremonies, namely proposal, engagement, wedding and post-wedding visit to the bride’s home. All contacts between the two families must go through the matchmaker so this person is chosen carefully by the groom’s family, who must be smooth-tongued and have a happy family with many sons.

In the past, Ngai marriage was of trade nature. Wedding presents exacted by the bride’s family included 40 cans of sticky rice, 60 cans of ordinary rice, 50 liters of liquor, 100 kg of pork and jewelries, including a ring, a pair of earrings and a set of silver chatelaines, and ten or twenty silver coins, which were contained in bamboo baskets stuck with red papers. The quantity of all these offerings must be in an even number. Today, the wedding offerings are much simpler, placed in five or seven trays and including money also. The wedding invitations are delivered to guests by two young girls. On the wedding day, the matchmaker and an aunt of the groom come to the bride’s family to take the bride home and the groom only picks up his bride midway. According to Ngai old custom, before leaving for her husband’s home, the bride is supposed to cry for three days to show her gratitude to her parents for raising her up. Nowadays, this rule is no longer practiced. After the wedding day, the couple and the matchmaker visit the bride’s family to thank her parents, bringing two chickens, two bottles of liquor and a tray of sticky rice as presents.

The Ngai believe the more children they have the richer they are. When getting pregnant, a woman receives good care from her family, clan and community. She is not supposed to do hard work and must follow strict diet, believed to make the future baby healthy. A pregnant woman is not supposed to eat buffalo, dog and goat meat, snail, fishes without scales, bamboo shoots, pumpkin and cress which are believed to make her delivery difficult. There are also a host of taboos for her, such as entering the house through the main entrance door, sitting opposite the kitchen door and on firewood, entering the buffalo breeding facility, sleeping at her parents’ home, stepping over a buffalo horn and buying new clothes.

A Ngai woman gives birth at home with assistance from her mother or mother-in-law or a midwife. The infant’s umbilical stump and placenta are buried in a bamboo cylinder container. The mother is not supposed to have a bath or go out in the first 15 days after her delivery. After that, she can have a bath, using water boiled with forest leaves. Nutrious foods for the mother include chicken steamed with Panax pseudoginseng and other Chinese traditional herbs, pig feet porridge and chicken eggs soaked in liquor.

When a family has a newborn, it hangs a branch of green leaves in front of the house, a signal that strangers are not welcomed. This taboo lasts for seven days if the child is a boy and nine days for a girl. After that, villagers can visit the mother and child and each guest will be offered a cup of rice wine, believed to keep the child away from misfortunes. A baby is named right after birth. The patenal grandfather gives name to the first newborn if he is a boy and either the patenal or maternal grandmother has this honor if she is a girl. The following children are named by their parents.

The lunar new year festival of the Ngai starts on the 23rd of the last lunar month when offerings are made to the kitchen god to see him off to heaven. On the lunar new year’s eve when the kitchen god is believed to return home, every Ngai family holds an offering ritual to welcome him and ancestors to celebrate the lunar new year festival with the family. The offerings include banh chung, sweetened bean porridge, meat and vegetarian dishes. The group has the custom of sticking red papers onto every object, from farming tools to trees in the new year.

On the first day of the new year, they are not supposed to kill animals, sweep the floor, say bad things or ask for water or fire from others. The Ngai still retain other lunar new year practices like other groups such as erecting cay neu (new year pole set up in the courtyard of every family), inviting a person to be the first visitor in the new year to bring luck to the family, li xi (giving lucky money to children) and setting out on the first day of the new year. On the third or fourth day, another offering ritual called hoa vang (burning votive papers) is conducted to end the new year ceremony and see off ancestors to heaven.-