>>Pot Dam, an indispensable ceremony for every Thai bride

>>Cremation, an age-old custom of the Thai

>>Xen lau no, Thai ceremony honoring witch doctors

>>Spending the night in a Thai home

>>Hair washing ceremony of the Thai

>>New rice ceremony of the Thai

>>Matrilocality challenges Thai grooms

Having evolved along with historical developments of the Thai, customary law has become an effective tool to regulate the society of this ethnic group.

Thai customary law, called in Thai language hit khoong ban muong (law of the village), has for long been recorded in writing and regarded as official rules to be obeyed by the whole community. The law covers the history of the village, the village management apparatus, powers and benefits of village leaders, obligations and benefits of villagers, community veneration rituals, punishment and reward in ownership, marriage and family relations, protection against bodily infringements, and traditions and practices related to wedding, funeral and worship. Thai customary law not only expresses original cultural traits but has significant values in social management.

|

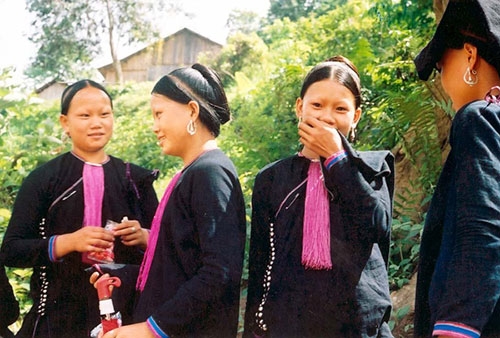

| White Thai women perform a folk dance in their traditional Com costume__Photo: Quang Duy/VNA |

Rules on production, ownership, management and use of natural resources

As irrigation plays an important role in wet rice farming of the Thai, under their customary law, every villager has the obligation to join the building and protection of the village’s irrigation works organized by the village board. Destroying irrigation facilities is subject to heavy fine.

Cattle rustling is also heavily punishable as it is regarded as an act of destroying production. A rustler who is caught red-hand must work as a servant for the village head. A person who intentionally lets his buffalo butt and kills another buffalo must compensate two buffaloes.

Thai law says that a village owns land, forests, rivers and natural resources on its clearly defined territory. Land, forests and natural resources are under common ownership and can be exploited by every villager.

Meanwhile, farmland is regarded as community property which is distributed to village leaders and villagers. A villager may give his farmland to another villager but may neither sell nor give it to an outsider. If a family moves to another place, its farmland will be divided to other families in the village. Villagers have to perform community work in proportion to the farmland they receive.

Everyone can pick forest products but has to give part of them to village leaders. Thai customary law bans exploitation in forests that provide sources of water and timber for the village and forests used for community hunting and rituals.

Those destructing land and forests must, in addition to paying a fine, carry out certain formalities to redeem their guilt because destruction of forests is regarded as an act of offending gods. This religious belief has encouraged humanist behaviors toward nature in the Thai community, helping prevent destruction of nature.

Rules against social vices

Thai customary law considers adultery and theft contemptible acts which must be severely punished.

When a man discovers another man having an affair with his wife, he can kill that man without being penalized.

Thieves are subject to heavy punishment, no matter the stolen objects are valuable or not.

A person who steals rice is fined 15 taels of silver. But if he does so because of food shortage at a time of crop failure, the fine is reduced five times and the thief may even keep half the stolen rice.

Scolding is also considered an evil act to be punished. A person who scolds another is fined one tael of silver, a pig and liquor. If he scolds his parents or parents-in-law, the fine is liquor, three or five taels of silver and a pig or a buffalo respectively. The fine is increased to 15 taels of silver, a buffalo and liquor if he scolds the village head. The punished person also has to give liquor and pork as offering for holding a ritual dedicated to the spirit of the scolded person.

Beating a person is fined between three and twenty five taels of silver together with liquor and a buffalo as the offering to the spirit of the beaten person.

A murderer is punished to death but can avoid this penalty if he pays a fine to the village, a murder fine and all expenses for the funeral of the victim. Under Thai law, relatives of a victim are prohibited from killing the murderer. Such revenge is subject to the highest punishment of death.

Rules on marriage and inheritance

Under Thai customs, people are free in love and marriage. Marriage must go through a matchmaker who will visit the bride’s family three times before the wedding. In the first visit, the matchmaker brings two packs of tea, asking the woman’s parents to permit the couple’s love affairs. If getting their consent, the matchmaker comes to see the bride’s family again, bringing four bottles of liquor, 100 sticky rice cakes, two packs of tea and betel and areca as proposal presents. In the third visit to propose the wedding, the matchmaker brings a pair of chickens, 200 sticky rice cakes, four bottles of liquor, two packs of tea, betel and areca, and a dress and two silver bracelets for the bride’s mother. On the wedding day, the groom’s family brings to the bride’s a pig, three jars of ruou can (rice wine drunk out of a jar through stalks), 300 kilos of rice and eight taels of silver for preparing a feast for the bride’s family and their relatives and friends before taking the bride home. Three days after the wedding, the husband and wife return to her home where a party is held to welcome the son-in-law. A ceremony for the newly weds to enter the bridal chamber is also held, marking the official recognition of their marriage by the bride’s family.

A couple whose love is protested by their families can flee to another village and return later when already having children. A fleeing couple who are caught by the village can hold a wedding if so consented by the village head. If the couple are not caught, the man’s family must pay a compensation called gia dau, which means payment of gratitude to the bridal parents. This sum of money is also paid by the groom’s family in any Thai wedding, which includes five silver coins as a present to the bride’s mother for raising up the bride, a sum of money agreed by the two families to cover part of expenses of the bride’s family, and a compensation in cash or in kind for the groom’s matrilocality, which is also agreed by the families. If the groom’s family does not pay the matrilocality compensation, the groom is required to stay at his wife’s between eight and twelve years after the wedding.

Under Thai marital rules, the bride’s family must return the groom’s all the costs paid by the latter for the wedding should the bride die within eight months after the wedding. This payment is reduced to half or one-third should the bride die 11 months or one year later respectively. But the groom’s family can only ask for this compensation if it has considerately held the funeral for the daughter-in-law. If the wife dies after having a child, her family does not have to pay compensation as the child represents his mother in the paternal family.

Thai law requires husband and wife to be faithful and kind to each other throughout their whole life. The family of a husband who does not take care of his wife when she gets sick is fined 35 taels of silver and has to offer a buffalo and liquor in a ritual dedicated to the ancestors of the wife’s family. Vice versa, the wife’s family is subject to the same fine and has to additionally pay five taels of silver, a buffalo and liquor for the offering ritual dedicated to the spirit of the husband.

Even though backing faithfulness in marriage, the Thai allow divorce but at certain costs, under which the wife’s family has to pay compensation to the husband’s if the wife initiates the divorce. Otherwise, she is not allowed to get divorce. If both husband and wife agree to the divorce, their common property is divided equally and the mother raises daughters and the father, sons.

When her husband dies, a woman can re-marry but under the arrangement of her husband’s family. Without such arrangement, her family must return her husband’s all the costs paid by the latter for the wedding.

Under Thai custom, only sons have the inheritance right while daughters just receive dowry. Estate division follows the principle that older brothers get two-thirds of the property, under which the property is divided into three portions and the oldest brother receives two. The remaining part is further divided into three and the second oldest brother gets two. The remainder will be divided according to this principle to the younger brothers. In a family with many sons, the oldest and second oldest brothers may give part of their inherited property to the youngest brother. The property of a person who dies without heirs will be given to members of his family line.